What difference does Christianity make in the practice of history? In most respects, Christian historians practice their discipline just like other historians; our religious beliefs — or anyone else’s — are no substitute for thinking historically about the past, analyzing and synthesizing historical evidence, and writing compelling narratives. But the longer I do this, the more convinced I am that something as important as my identity as a follower of Jesus Christ has to have something to do with my vocation and profession.

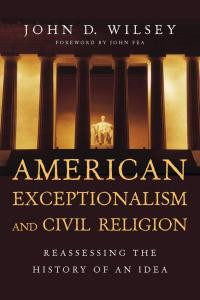

For example, I’ve often come back to the three Pauline virtues and asked myself, Shouldn’t history as written and taught by Christians be faithful, hopeful, and loving? That same question seems to have been in the back of the mind of one Christian historian I admire, John D. Wilsey, as he read the work of another Christian historian I admire, Kristin Kobes Du Mez.

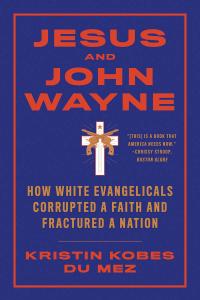

In a recent review for the online journal Ad Fontes, John acknowledges the significance of Kristin’s much-discussed book, Jesus and John Wayne. “To say that this book is important, that it should be widely read, that it should be taken seriously, is obvious,” he concludes, adding that the “most singular value that Du Mez’s book has for us as Christians seeking to submit our lives to the Scriptures—those of us who would classify ourselves as complementarians, conservatives, evangelicals—the book forces us to examine ourselves.” And yet, he also finds J&JW an example of “history as social and political posturing, the firing of salvoes in the culture wars…. Du Mez’s work reads less as history and more as ideology, and an ideology with little in the way of faith, hope, or charity.”

In a recent review for the online journal Ad Fontes, John acknowledges the significance of Kristin’s much-discussed book, Jesus and John Wayne. “To say that this book is important, that it should be widely read, that it should be taken seriously, is obvious,” he concludes, adding that the “most singular value that Du Mez’s book has for us as Christians seeking to submit our lives to the Scriptures—those of us who would classify ourselves as complementarians, conservatives, evangelicals—the book forces us to examine ourselves.” And yet, he also finds J&JW an example of “history as social and political posturing, the firing of salvoes in the culture wars…. Du Mez’s work reads less as history and more as ideology, and an ideology with little in the way of faith, hope, or charity.”

Let me reiterate my admiration for both historians and my appreciation for their work, in the ways that it is similar (rigorous research, thoughtful and often thought-provoking analysis, clear and compelling writing) and in the ways that it is different. Having regularly used this blog to praise Kristin, let me do the same now with John. As a historian of U.S. foreign policy, I learned much from his study of American exceptionalism, and this fall I want my Cold War students to engage with his recent book about John Foster Dulles, which preceded mine in the same series of religious biographies.

But if I’m more sympathetic than John to what Kristin is doing in J&JW, that doesn’t mean that I’m unsympathetic to his concern that Christian history be marked by faith, hope, and love. I just think that I may understand differently how those virtues work themselves out through the practice of history. Because I see all three in Jesus and John Wayne.

Faithful History

I currently serve on the tenure and promotion committee for college faculty at Bethel, so hardly a week goes by without me applying to colleagues a criterion that would seem out of place in other academic settings: their ability to integrate faith and learning in their teaching and scholarship. Early this summer, I’ll again co-lead the workshop meant to help Bethel faculty coming up for tenure and promotion to write their “faith integration” essay. So you can assume that I’m convinced that Christian faith ought to inform academic practice by Christians.

Even if they don’t realize it, all scholars are shaped by what Nick Wolterstorff calls “control beliefs.” So it’s obviously important that Christian historians consider how their religious convictions influence their motivations and interpretations. But how they do this might seem more implicit or explicit, depending on the historian and her context..

For example, I think you could read through 98% of my biography of Charles Lindbergh and not know that, unlike my subject, I am both religious and spiritual. Lindbergh was an occasional admirer of Jesus as an ethical teacher, while I’m a follower of Jesus who knows him as our Christ, but my purpose wasn’t to rebut Lindbergh’s theology. Still, in the background of the entire book, and coming to the foreground at key moments, is my belief that God created humanity in God’s image. To my mind, that both motivates telling the story of a life and made it impossible for me to avoid wrestling in view of my (mostly Christian) readers with Lindbergh’s rejection of basic human worth, dignity, and equality.

Likewise, it seems clear to me that Kristin’s criticism of white evangelical patriarchy is motivated, at least in part, by her faith as a Christian who takes seriously the pervasive effects of the Fall — and our inability to recognize our own sinfulness. As a historian of culture and gender, she is drawing on the theoretical insights of thinkers who are not animated by Christian faith, but as a study of sin, Jesus and John Wayne strikes me as an exemplar of the Calvinist model of faith-learning integration that shapes so much discourse about Christian scholarship.

Loving History

As a Pietist, though, I tend to ascribe less importance to fusing scholarship with faith understood as a set of doctrines and look more for the actual effects of faith — as a transformative gift of God reshaping us from the inside-out — in a scholar’s life. In that sense, Christian history needs to be more than faithful; it must make evident the fruits of the Spirit, including what Paul says is the greatest of the virtues: love.

After all, the apostle writes, “the only thing that counts… is faith working in love” (Gal 5:6). Can Christian history truly reflect Christian faith if it’s not working — being made active or effective — in love?

To that end, John’s review of Jesus and John Wayne appeals to one of my favorite essays about Christian history: Beth Barton Schwieger’s “Seeing Things,” in which she argues that history is an act of loving our neighbors in time — in particular, those who are dead. Before my Intro to History students get too far into their research projects this semester, I’ll have them consider Schwieger’s caution that historians have power over their deceased neighbors in the past. The dead are, as John puts it, “at our mercy–they cannot come back and offer their explanations, their justifications, their apologies, or their acts of restitution.” So we must act with humility and empathy, and perhaps hesitate to judge them too quickly or too harshly.

To that end, John’s review of Jesus and John Wayne appeals to one of my favorite essays about Christian history: Beth Barton Schwieger’s “Seeing Things,” in which she argues that history is an act of loving our neighbors in time — in particular, those who are dead. Before my Intro to History students get too far into their research projects this semester, I’ll have them consider Schwieger’s caution that historians have power over their deceased neighbors in the past. The dead are, as John puts it, “at our mercy–they cannot come back and offer their explanations, their justifications, their apologies, or their acts of restitution.” So we must act with humility and empathy, and perhaps hesitate to judge them too quickly or too harshly.

“This love is not sentimental, nor does this love absolve the subjects of their sins,” concedes John. “Loving the dead means we tell the truth about them, as far as it is possible given our limitations and the complexities of the past.” But he finds “little of Schweiger’s pastoral imagination reflected in Du Mez’s approach to evangelicals over the past century,” which judges some of those Christians and finds them wanting.

Correctly, in my estimation, even as I thought she did well to seek to understand what led her subjects into “militant masculinity.” But I take seriously John’s concern here: as I’m sure it was for him in writing his Dulles biography, it was ever always in the back of my mind that Charles Lindbergh was at my mercy. Whenever that infamous pilot offended or infuriated me, I threw back at myself my admonition to students that history teaches us humility, empathy, and comfort with complexity. By the end of the book, I did render a measure of judgment on Lindbergh, but more, I tried to invite what another Christian historian, Robert Tracy McKenzie, calls moral reflection: holding up Lindbergh’s life as a mirror for our own sins — mine and my readers’.

To tell the truth about Lindbergh is to document his racism and anti-Semitism, but also to explain where it came from and to see him as a multi-faceted person worthy (as one endorser put it) of “adulation, pity, and scorn.” In that sense, I tried to love Lindbergh as my neighbor.

But along the way, I realized that a key benefit of a Lindbergh biography is that it helps us to see and love people he couldn’t really see or love: the Jewish refugees he reviled and other victims of the Nazi regime he admired; the persons of color he saw as threats to global white supremacy; and all others whose worth he was willing to sacrifice to a notion of “the quality of life” that initially emerged from eugenics.

Likewise, Jesus and John Wayne struck me as an example of Christian history being loving because it helps its readers to love past neighbors who suffered under the toxic mix of patriarchy, militarism, Christian nationalism, and racism that Kristin describes.

The heart of Wilsey's critique is my lack of empathy as a Chr historian. Perhaps. But I'd argue that empathy must extend not just (or even primarily) to those who've wielded power but also to those w/out institutional& religious power. J&JW centers experiences of the latter.3/

— Kristin Du Mez (@kkdumez) February 9, 2022

Hopeful History

Love is “the greatest” of Paul’s three virtues, but the one that I ponder the most is hope. In fact, when I came up for tenure at Bethel, I wrote my own faith integration essay on that theme. “Integrating that virtue with the study of a past age,” I mused in 2007, “presents real theoretical and practical challenges. Can I study history hopefully when hope seems as foreign to that academic discipline as it is essential to a life spent following Jesus Christ?”

On the one hand, hope primarily orients us towards the future, which is beyond the ken of historical methods that have a hard enough time reconstructing and interpreting the past. And studying a past as warped by sin as, say, the 20th century mostly leaves me feeling dispirited, if not cynical.

On the other hand, how could history be meaningfully Christian if it brackets off one of the Christian virtues, a source of strength (Isa 40:31), endurance (1 Thess 1:3), and steadfastness (Heb 6:19), that (in Eugene Peterson’s paraphrase of Colossians 1) keeps “taut” the “lines of purpose in [our] lives”?

I do think there are reasons for Christian history to be hopeful. First, if history does nothing else, it makes us realize the potential for change over time. Historians can discern movement from ignorance toward understanding, from oppression toward justice, from captivity toward liberation, from suffering toward flourishing.

But Christian hope can keep taut lines of conflicting purpose; Christians sometimes disagree whether they want what’s done to be undone. And even when we are of one mind, we know that the arcs of truth, justice, etc. bend unpredictably, rarely in one direction at once, and then only with great difficulty: in the face of stubborn resistance, often at terrible cost to many people. I’m hardly surprised that John came to the end of a book like Jesus and John Wayne and found “no apparent hope.”

I've openly shared numerous times that I struggled to find hope when I came to the end of my book. I didn't set out to write this narrative. As the narrative took shape, I became less & less hopeful of change. Yet many readers do not find the book without hope. 15/

— Kristin Du Mez (@kkdumez) February 9, 2022

So while I agree with John, in a sense, that “hope is central to a Christian historical method,” I think it’s for a different reason: less because evidence or narratives ought themselves to encourage or reassure us, but because the act of studying what’s old helps Christians to follow a God who is making all things new.

Even the most sobering, dismaying history is hopeful, then, because of what it does to its students. First, it churns the soil — unsettling the layers of certainty, bias, and ignorance that build up in all of us, so that we’re better able to question what is and consider what could be — then it plants seeds of change, which rarely germinate by the end of a book or a semester, but can bear unexpected fruit in the lives of individuals, the church, and the world.