I have been posting about the borderlands of empire, territories beyond the tight control of rival realms. Some of those buffer states, those often-neglected liminal kingdoms, have a special significance in the history of religion. Arguably, early Islamic history makes little sense except in the context of two remarkably influential tribal powers, which together represent a lost Christian realm. The new religion of Islam emerged from these embattled borderlands.

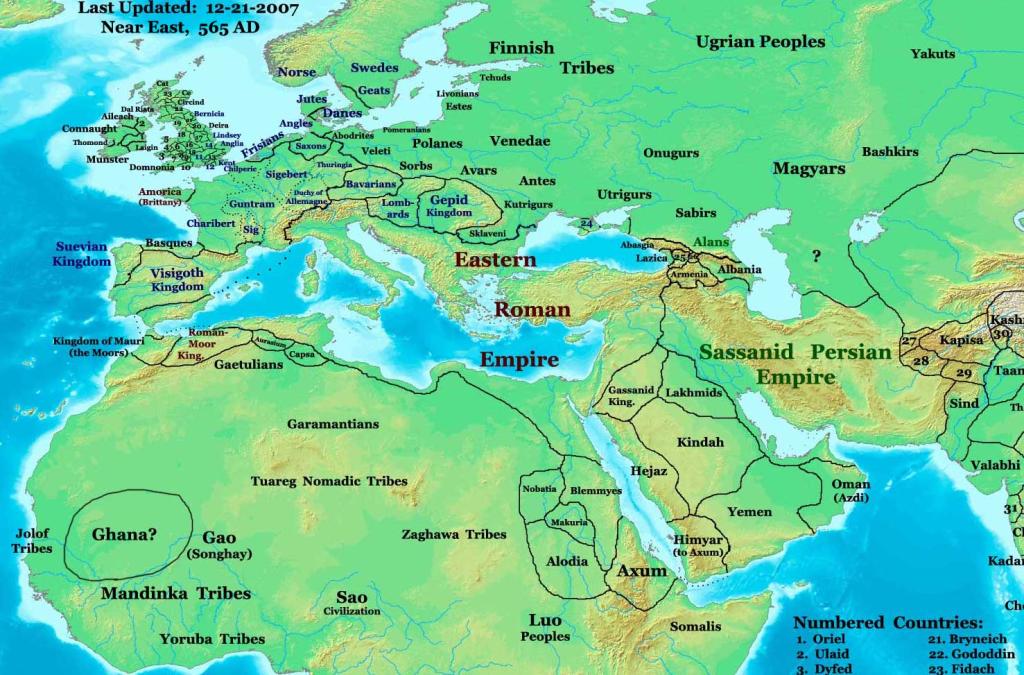

A familiar myth suggests that it was mainly the force of Islam that brought Arab peoples into the traditional heartlands of the civilized Near East, around the 630s. We perhaps visualize this in terms of memories of massed camel charges from Lawrence of Arabia – though camels really had nothing to do with those early Islamic conquests. In reality, Arab tribes and ethnic groups were very powerful indeed long before this, and some formed influential states in the lands that we would today think of as Jordan, Iraq and Syria, territories contested between the two great empires. To the west stood the Ghassanid kingdom, the “Sons of Ghassan,” allied with Rome. In the east were the pro-Persian Lakhmids, with their capital at al-Hira.

The Ghassanids arrived in the region as refugees from further south in Arabia, possibly as Christians fleeing persecution by Jewish tribes. From the fifth century they formed a powerful state, which became vastly more powerful in the sixth century as the wars between Rome and Persia escalated. The Byzantine Empire relied heavily on Arab allies (foederati) like king al-Harith (“Arethas”) and his son al-Mundhir. Far from being barbarians, the kingdom was deeply integrated into the Byzantine politics of the day. In modern terms, think of the Ghassanids as the empire’s surrogate forces.

The Ghassanid leaders were also strongly Christian, and they were mainstays of the Syriac-speaking Monophysite/Miaphysite churches. The sixth century kings ensured that the Syrian Monophysite church survived and flourished under their protection, creating a powerful Middle East tradition that endured for centuries. Al-Harith was the patron of Jacobus Baradeus, the church’s wide-ranging evangelist (hence the church being known as the “Jacobites”). This story exactly fits the pattern I outlined above of religious traditions persecuted in one region being able to flee for safety across a convenient border, of “refugee faith.” Later Ghassanids refused conversion to Islam, and many of their descendants remained Christian until modern times.

Although they served the Persians, the Lakhmids also included a strong and deeply rooted Christian element. Al-Hira was an important bishopric of the Church of the East.

The landscape in which the Ghassanids operated included several cultural and religious centers that would be critical for both Christianity and early Islam. One was Sergiopolis (Resafa), the beloved shrine of the martyr saint Sergius, and effectively the religious capital of a wide region of what is now Syria and Iraq. In the sixth century, it was the seat of a Christian metropolitan, with five suffragan sees. As so often happened in Western Europe, later medieval rulers continued to build in and around such ancient religious shrines, so that Sergiopolis became the spectacular palace of the eighth century Caliph Hisham.

Another great Ghassanid hub was Bostra, the Christian metropolitan see of Arabia. It featured extensively in later legend as the place where the prophet Muhammad met the Christian monk Bahira, who supposedly acknowledged his prophetic destiny.

It’s not just the border states that matter in this story. It’s the border cities like Resafa and Bostra, the entrepôts for all kinds of trade and exchange, spiritual and cultural no less than commercial.

By the seventh century, both empires were facing growing difficulties from their client states. The Lakhmids rebelled openly against the Persians, while religious divisions made the Ghassanids ever more discontented with Roman rule. These conflicts formed the background to the new movement of Islam. Reputedly, the Lakhmids helped the Muslims against their former Persian enemies.

But even after Islam had triumphed, the two Arab kingdoms exercised a lasting influence on the new empire, which still based itself in their former territories. I have already suggested how highly the new Muslim rulers valued places like Bostra and Resafa. In the East, al-Hira was supposedly the place where the Arabic alphabet was created. It is very close to Kufa – hence “Kufic” script. Others attribute that script to the Christian Arabs of al-Anbar

Some scholars go much further in proposing Christian influence over the emerging Islam. For one scholar, Christoph Luxenberg, the Qur’an demonstrates a Christian Syriac literary background that could certainly not have arisen in Mecca or nearby parts of Arabia, which had no adequate schools or libraries. Instead, he suggests, the Qur’an originated in a Christian environment in al-Hira or al-Anbar – and so, by implication, did much of the faith of Islam. Although that idea is highly controversial, there is no doubt that the old Christian Arab world left a substantial inheritance.

G. W. Bowersock has some indispensable books on this era, such as The Crucible of Islam (Harvard University Press, 2017). See also key books on the Arabs before Islam by Irfan Shahid.