The last two months have been an interesting time to be a historian of World War II. People shocked by the cynical brutality of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have understandably harkened back to 1939, the last time that a European power invaded one of its sovereign neighbors on dubious pretexts. Two powers, actually — the Soviet Union took its share of Poland two weeks after Nazi Germany seized its half. Later that year Stalin’s forces invaded Finland, then swallowed up the Baltic Republics while the rest of the world watched France capitulate to the Blitzkrieg.

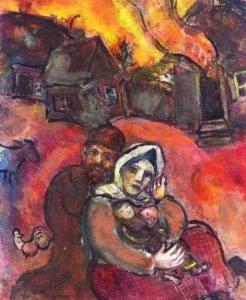

And as we’ve watched millions of Ukrainians flee their homes, while the bodies of civilians who couldn’t escape are discovered to be the victims of Russian war crimes, it’s no surprise that a WWII-era painting started to circulate on social media late last week: Marc Chagall’s poignant painting, “The Ukrainian Family.”

“Could’ve been painted today,” lamented an art therapist on Twitter. One of a series of gouaches — rather thick watercolors — that Chagall completed between 1940 and 1943, while living in exile in France and the United States, “The Ukrainian Family” certainly speaks to universal themes of how civilians experience the violent dislocation of war, and perhaps to the particular experience of people in a part of the world not far from Chagall’s birthplace, now in Belarus and itself a victim of Nazi aggression in 1941-1943.

But as legal historian and Holocaust educator Eric Muller pointed out, it’s important to understand that Chagall was not painting just any Ukrainian family, but a Jewish one fleeing a shtetl like those he had known firsthand on the Pale of Settlement. (See Nadya’s recent reflection on the invasion as a descendant of Ukrainian Jews.) And, as so often in his career, Chagall intentionally used Christian symbolism to convey the tragedy of the Jewish experience.

When “The Ukrainian Family” was auctioned off for over half a million dollars in 2007, the Christie’s description quoted Chagall biographer Franz Meyer, who saw in its flaming colors and gaunt faces “the pain felt by [Chagall] himself through his sympathy with the fate of his nation and the horrors of war.” But “his nation” carried several connotations: the Soviet Union and its nationalities; his adopted homeland of France; and, most evidently in this case, the Jewish people.

Indeed, if you didn’t know it was painted in the early 1940s, you might assume that Chagall meant to depict a Jewish family fleeing one of the many pogroms that plagued the Russian Empire of his childhood. (He was born in 1887.) Early in Putin’s invasion, nothing moved me so deeply as the sight and sound of a tearful rabbi closing his synagogue in Odessa, whose Jewish population survived at least five pogroms between 1821 and 1905 and then was butchered by Romanian troops in late 1941. Or if Chagall did mean to depict events contemporary to the German invasion and occupation of the Soviet Union, it’s not impossible that both the family and its unseen tormentors were Ukrainian, given how effectively the SS tapped into local anti-Semitism in that part of the USSR.

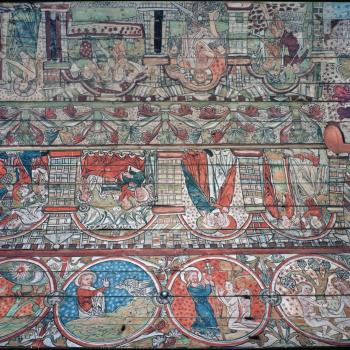

In any event, the people off-canvas who set the painting’s fires were almost certainly Christian. So it’s remarkable that, as Avram Kampf put it, “Chagall expresses, by means of symbols deeply embedded in the art of the Christian West, the tragic events of the Holocaust and some aspects of its profound religious and historical dimensions” (emphasis mine).

That response to the coming Shoah predated World War II. After the pogrom known as Kristallnacht moved Europe’s Jews one step closer to Hitler’s Final Solution, Chagall painted “White Crucifixion,” in which the cross is positioned above a menorah and Jesus (labeled “King of the Jews”) not only wears a prayer shawl as a loincloth, but looks down on images of a burning synagogue, a man rescuing a Torah scroll, and Jewish refugees and mourners. “Chagall’s painting,” says its description at the Art Institute of Chicago, “passionately identifies the Nazis with Christ’s tormentors and warns of the moral implications of their actions.”

According to Jonathan Wilson, Chagall painted at least a dozen crucifixions during the war years. In 1940’s “The Martyr,” for example, biographer Lionello Venturi finds that the Christ figure “is not God… he is the embodiment of human sacrifice.” Bearded and wearing a peasant’s cap rather than a crown of thorns (or halo), he also looks more than a little like the father in “The Ukrainian Family,” which draws less overtly from Christian iconography — unless you agree with Christie’s that its mother looks “Madonna-like,” in which case we might be prompted to think about the connections between the Holy Family and their fellow refugees fleeing Ukraine today.

Why did Chagall use Christian symbols to convey Jewish suffering? Perhaps it was simply the best way he knew to wrench open Western eyes to what was happening to the East. Or it painfully underscored how a religion whose founder was murdered had itself produced murderers. To Walter Erben, Chagall saw “the figure of Christ as the great poets see it: as the merciful Saviour of whom it is written, ‘Then they cry unto the Lord in their trouble and he saveth them out of their distress’ [Ps 107:6], and who has already suffered through his prophesied martyrdom all the agonies and humiliations ever destined for man.”

Jonathan Wilson, writing in the Wall Street Journal the same year “The Ukrainian Family” went up for sale at Christie’s, found a more complicated set of meanings:

Chagall’s relationship to the figure of Jesus Christ is ultimately mysterious and unclassifiable. It is the Jesus of a Jewish child who grew up in an environment of Russian Orthodox churches; of a Jewish painter both attuned to and rebelling against a 2,000-year tradition of Christian iconography in art; of a Jew in love with the stories of the Hebrew Bible and yet well versed in the parables of the New Testament, drawn to the poetry of that book and excited by its gaunt philosophy; of a Jew who wanted to argue Christ with the Lubavitcher Rebbe but who soon after, as a Soviet revolutionary, decried religion; of a pagan who illustrated the Hebrew Bible; of a Jew in mourning, via images of Jesus, for Nazi murder and the destruction of the world he had grown up in. All this takes us a long way from “Fiddler on the Roof.”

In any case, the recent use of “The Ukrainian Family” serves as one more reminder that while humans understandably interpret their confusing present in light of what seems like a knowable past, historical analogies often strip away layers of meaning.