Today we welcome Allie Roberts as a guest contributor to the Anxious Bench. Roberts is a PhD student in the History department at Baylor University. Her research focuses on Black women’s leadership and grassroots activism during the twentieth century, particularly during the US civil rights movement.

In the United States, some Christians profess a faith undergirded by white supremacy, patriarchy, and power. Recently, stories about those who abuse their power and suppress others while claiming Christ capture our attention, and rightfully so. Importantly, though, for as long as oppressors have justified their violence by declaring their adherence to Christianity, others pursuing Christian justice have resisted. As far back as the nineteenth century, Black women sought justice, maintaining the belief that God called them to work on behalf of the oppressed, poor, and marginalized. Understanding their activism means taking seriously how they understood their lives and roles in pursuit of a holistic—or intersectional justice. They lived their theological convictions and led with the reassurance that God guided them, heard their prayers, and protected them as they sought racial, gender, and class justice as Black women.

“Lord, I cannot go!” Julia A. J. Foote cried when she received her call to preach. Born to previously enslaved parents in the North, Foote experienced racial discrimination, and she knew that as a woman preacher in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, men would attempt to cast her aside. Her belief in God’s salvation superseded those challenges. She eventually relinquished her opposition to the call, saying “I will go, Lord.” Foote preached, evangelized, and labored for Christ, believing that the Christian faith could bring earthly justice and peace for Black people. She spoke in pulpits across the country, addressing Black and white audiences, and calling parishioners to heed God’s command to love. To turn toward the gospel, she believed, meant to turn away from the sins of racial and gender prejudice.

Foote encouraged other women to pursue justice through ministry. “Sisters, shall not you and I unite with heavenly host in the grand chorus?” she wondered. “If so, you will not let what man may say or do, keep you from doing the will of the Lord or using the gifts you have for the good of others.” God called women to preach, lead, and pursue justice, Foote contended, and she hoped that others would listen and respond in recognition of the gospel’s indictment of racial and gender oppressions.

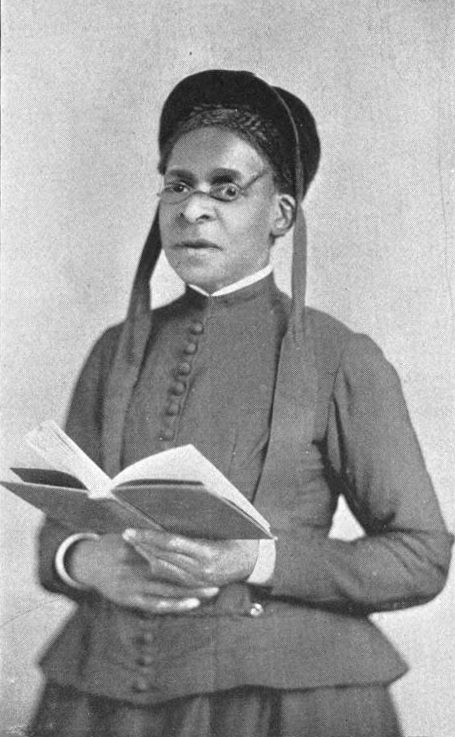

As a poet, abolitionist, and co-founder of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper also responded to racial and gender injustice through organizational activism shaped by Christian faith. Engaging scripture, Harper claimed that Christians should aid those in need and serve others because “when we best serve man, we also serve Our God.” Harper advocated for Black women’s schooling and suffrage through her work within interracial organizations such as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and the National Council of Women. Within these organizations, though, Harper found herself at odds with white women. As she advocated for education, economic opportunities, and equality for Black women, white women maintained a limited view of equality, often excluding racial justice from their initiatives.

Despite this opposition, Harper maintained that her holistic efforts aligned with God’s will. Resistance to equal rights extended back into Christ’s life, as those who sided with empire despised his gospel to the poor and killed him in their grasp to maintain power. Harper resolved that there was no such thing as partial equality. She warned: “I would not change souls with a man who reproaches his God by despising His poor!” Faithfulness to God called for comprehensive care. She resolved to be faithful to the Christian mission and holistic justice.

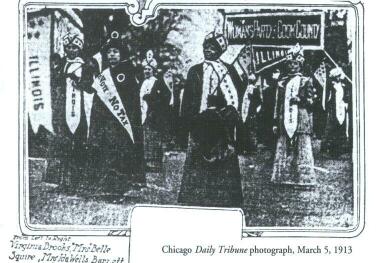

Ida B. Wells-Barnett pursued far-reaching justice as the infamous leader of anti-lynching crusades in the 1890s, a renowned journalist, and a co-founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Like Foote and Harper, Wells-Barnett engaged Christian principles as she continually fought against racial, gender, and class injustice. She also experienced discrimination in her own organizations, even as she worked to dismantle it. Men pushed her out of formal leadership opportunities in the NAACP, and white women accepted southern segregation within women’s suffrage organizations.

In the midst of persistent injustice, Wells-Barnett found it difficult, even impossible, to comprehend a just God. “O God is there no redress, no peace, no justice in this land for us?” she lamented. But she resolved, “God is over all & He will, so long as I am in the right, fight my battles, and give me what is my right.” Faithful in her strivings, she worked alongside men and women, Black and white, inside of and outside of church walls. She continually resisted narrow visions of justice that denied her full humanity. As she worked against white supremacy, sexism, and class oppression, she insisted other Christians needed to do the same.

Activist Mary Church Terrell worked alongside Wells-Barnett in anti-lynching campaigns and founded the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs with Wells-Barnett, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, and Harriet Tubman. Terrell advocated for Black women’s suffrage, protested segregation, and worked as a teacher and school administrator. As she faced oppression in her life and work, she found relief in her faith. “It is a blessed dispensation of Providence,” she held, “that the good great women and great men do is not confined within the narrow limits of a lifetime.”

Eternal reassurance, though, did not negate earthly work. Terrell held that the “barbarities which mock the civilization and Christianity of the US at the present time” would continue without resistance against oppressive forces. Throughout her life, she spoke powerfully to national and international audiences, advocating for intersectional justice. Speaking to an audience at the National Woman Suffrage Association Convention in 1890, for instance, Terrell contended that “A white woman has only one handicap to overcome—a great one, true, her sex; a colored woman faces two—her sex and her race. A colored man has only one—that of race.” Her activism continued throughout the twentieth century, and she felt that activists would not achieve the justice she envisioned within her lifetime. “As wonderful as has been our progress,” Terrell conceded, “…we are still leagues and leagues from our goal.”

Black women activists in the nineteenth century committed to working for God in the world. Seeking comprehensive, Christian justice, they worked within and outside of church walls, in organizations, and in community with others. When Foote, Harper, Wells-Barnett, and Terrell cared for the least of these, they embodied the belief that Empire does not reign victorious. Today, as throughout history, many claiming to work under the banner of Christ do so in pursuit of power rather than justice—supremacy rather than equality. But they have never had a singular claim on the faith, as Black women activists have shown. In fact, Wells-Barnett might contend that their actions are “a terrible indictment of white civilization and Christianity.” To love one’s neighbors, to care for the poor, to work on behalf of the marginalized—these principles guided these Black women’s activist work. They knew the end of the story and in faith, sought to bring God’s justice on earth as it is in heaven.