There is an odd but very useful source on early Christianity that even now remains strangely unfamiliar to many writers on that topic. Even less known is the discussion by a totally unexpected nineteenth century source, which provides many insights that are still valuable. There is great material here for the sociology of religion, in any era.

In the late second century, the pagan satirist Lucian wrote the story of one Peregrinus, who died in the 160s. (He ultimately burned himself alive). Lucian presents Peregrinus as a Cynic, a rogue pseudo-philosopher who wanders from city to city, exploiting the gullible. For our purposes, there is a remarkable section when he is taken up by local Christians, who assume he has been persecuted for his faith in Christ. He lives very well off them until he moves on yet again. This is one of the few pagan sources of the period to mention Christians in any detail, even from a hostile point of view. (Some modern scholars treat Peregrinus’s Christian career much more seriously).

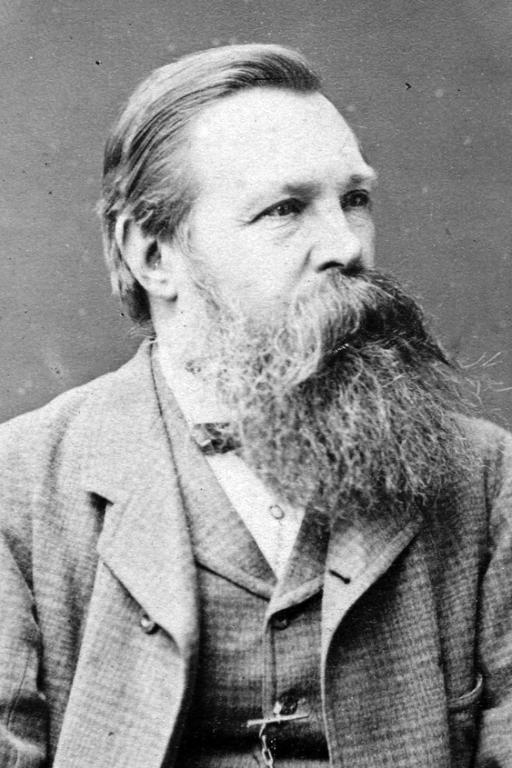

No less interesting, though, is the use of this story by Friedrich Engels, the partner and patron of Karl Marx. Engels had a deep interest in early Christianity as a social movement. Although he was a deadly enemy of the churches, he respected early Christianity as an authentic voice of the poor, before it was co-opted by the state and the institutional church. I should also say that his comments on these topics can actually be … well, pretty funny.

In the 1890s, Engels used the story of Peregrinus to frame that early situation. Remarkably, he was not using Lucian to depict Christians as fools, and he drew quite startling parallels between those early believers and the radical Left of his own day. In both eras, he says, there were dedicated activists for the poor, but if they were not careful, they tended to slide off into hare-brained schemes, and to fall for the manipulation of deceivers, tricksters, grifters, confidence tricksters, and what we might call cult-leaders.

In both eras, con-men could go a long way before being found out. A little apocalyptic preaching went a long way. It even helped when people began to find out what you were up to, as it was easy enough to dismiss charges against you as the result of the lying plots of an evil world. And as the radical movement developed, so it attracted flaky eccentrics who pinned their particular causes on the true doctrine of the mainstream movement.

Engels’s attitude to the early church fooled by Peregrinus is a sympathetic “Oh my, you also had to deal with rogues like that even way back then?” Engels himself can remember meeting people like Peregrinus in the leftist underground of nineteenth century Europe, which had plenty of would-be prophets and self-proclaimed messiahs.

Engels made no claims to be fair and balanced on this or any topic, but his account does ring true for the developmental stages of many new and emerging religious movements.

The Adventures of Peregrinus

You can read Engels’s account in full, but let me offer an excerpt here. Engels writes:

[Lucian] relates among other things the life-story of a certain adventurous Peregrinus, Proteus by name, from Parium in Hellespontus. When a youth, this Peregrinus made his début in Armenia by committing fornication. He was caught in the act and [nearly] lynched according to the custom of the country. He was fortunate enough to escape and after strangling his father in Parium he had to flee.

“And so it happened … that he also came to hear of the astonishing learning of the Christians, with whose priests and scribes he had cultivated intercourse in Palestine. He made such progress in a short time that his teachers were like children compared with him. He became a prophet, an elder, a master of the synagogue, in a word, all in everything. He interpreted their writings and himself wrote a great number of works, so that finally people saw in him a superior being, let him lay down laws for them and made him their overseer (bishop) …. On that ground (i.e., because he was a Christian) Proteus was at length arrested by the authorities and thrown into prison….

“As he thus lay in chains, the Christians, who saw in his capture a great misfortune, made all possible attempts to free him. But they did not succeed. Then they administered to him in all possible ways with the greatest solicitude. As early as daybreak one could see aged mothers, widows and young orphans crowding at the door of his prison; the most prominent among the Christians even bribed the warders and spent whole nights with him; they took their meals with them and read their holy books in his presence; briefly, the beloved Peregrinus” (he still went by that name) “was no less to them than a new Socrates. Envoys of Christian communities came to him even from towns in Asia Minor to lend him a helping hand, to console him and to testify in his favor in court.

“It is unbelievable how quick these people are to act whenever it is a question of their community; they immediately spare neither exertion nor expense. And thus from all sides money then poured in to Peregrinus so that his imprisonment became for him a source of great income. For the poor people persuaded themselves that they were immortal in body and in soul and that they would live for all eternity; that was why, they scorned death and many of them even voluntarily written by his sacrificed their lives. Then their most prominent lawgiver convinced them that they would all be brothers one to another once they were converted, i.e., renounced the Greek gods, professed faith in the crucified sophist and lived according to his prescriptions. That is why they despise all material goods without distinction and own them in common — doctrines which they have accepted in good faith, without demonstration or proof. And when a skilful imposter who knows how to make clever use of circumstances comes to them he can manage to get rich in a short time and laugh up his sleeve over these simpletons. For the rest, Peregrinus was set free by him who was then prefect of Syria.”

Then, after a few more adventures,

“Our worthy set forth a second time” (from Parium) “on his peregrinations, the Christians’ good disposition standing him in lieu of money for his journey: they administered to his needs everywhere and never let him suffer want. He was fed for a time in this way. But then, when he violated the laws of the Christians too — I think he was caught eating of some forbidden food — they excommunicated him from their community.”

A World of Cults and Cult-Leaders

Engels then offers his own interpretations, from his own time, where he finds lots of parallel cases. We note the near-total overlap between religious and political movements, a world of radical political networks, communes, and apocalyptic believers. We could be talking about the US at the same time, or indeed, around 1970. A cultural/spiritual explosion had created a perfect environment for an unscrupulous political/spiritual entrepreneur, and they saw rich opportunities. As Sammy Davis jr. sang in Sweet Charity,

Daddy, there’s a million pigeons

Waiting to be hooked on new religions.

This is what Engels tells us – and you don’t have to get every passing reference to people and movements to get the idea:

What memories of youth come to my mind as I read this passage from Lucian! First of all the “prophet Albrecht” who from about 1840 literally plundered the Weitling communist communities in Switzerland for several years — a tall powerful man with a long beard who wandered on foot through Switzerland and gathered audiences for his mysterious new Gospel of world emancipation, but who, after all, seems to have been a tolerably harmless hoaxer and soon died.

Then his not so harmless successor, “the doctor” Georg Kuhlmann from Holstein, who put to profit the time when Weitling was in prison to convert the communities of French Switzerland to his own Gospel, and for a time with such success that he even caught August Becker, by far the cleverest but also the biggest ne’er-do-well among them. This Kuhlmann used to deliver lectures to them which were published in Geneva in 1845 under the title The New World, or the Kingdom of the Spirit on Earth: Proclamation. In the introduction, supporters (probably August Becker) we read:

“What was needed was a man on whose lips all our sufferings and all our longings and hopes, in a word, all that affects our time most profoundly should find expression …. This man, whom our time was waiting for, has come. He is the doctor Georg Kuhlmann from Holstein. He has come forward with the doctrine of the new world or the kingdom of the spirit in reality”

I hardly need to add that this doctrine of the new world is nothing more than the most vulgar sentimental nonsense rendered in half-biblical expressions a la Lamennais and declaimed with prophet-like arrogance. But this did not prevent the good Weitlingers from carrying the swindler shoulder-high as the Asian Christians once did Peregrinus. They who were otherwise arch-democrats and extreme equalitarians to the extent of fostering ineradicable suspicion against any schoolmaster, journalist, and any man generally who was not a manual worker as being an “erudite” who was out to exploit them, let themselves be persuaded by the melodramatically arrayed Kuhlman that in the “New World” it would be the wisest of all, ie, Kuhlmann, who would regulate the distribution of pleasures and that therefore, even then, in the Old World, the disciples ought to bring pleasures by the bushel to that same wisest of all while they themselves should be content with crumbs.

So Peregrinus Kuhlmann lived a splendid life of pleasure at the expense of the community — as long as it lasted. It did not last very long, of course; the growing murmurs of doubters and unbelievers and the menace of persecution by the Vaudois Government put an end to the “Kingdom of the Spirit” in Lausanne — Kuhlmann disappeared.

This is a classic portrait of a nineteenth century messianic cult leader, the main novelty being that this is in Europe: that sort of character is much more familiar to us from the American situation. If you read German, there’s a detailed account of Kuhlmann’s career here.

Religious Fringe Movements Through History

Engels continues:

Everybody who has known by experience the European working-class movement in its beginnings will remember dozens of similar examples.

Today such extreme cases, at least in the large centers, have become impossible; but in remote districts where the movement has won new ground a small Peregrinus of this kind can still count on a temporary limited success. And just as all those who have nothing to look forward to from the official world or have come to the end of their tether with it — opponents of inoculation, supporters of abstemiousness, vegetarians, anti-vivisectionists, nature-healers, free-community preachers whose communities have fallen to pieces, authors of new theories on the origin of the universe, unsuccessful or unfortunate inventors, victims of real or imaginary injustice who are termed “good-for-nothing pettifoggers” by all bureaucracy, honest fools and dishonest swindlers — all throng to the working-class parties in all countries — so it was with the first Christians.

Hmm, “opponents of inoculation,” or as we might know them, anti-vaxxers – surely such strange people don’t exist in modern times?

All the elements which had been set free, i.e., at a loose end, by the dissolution of the old world came one after the other into the orbit of Christianity as the only element that resisted that process of dissolution — for the very reason that it was the necessary product of that process — and that therefore persisted and grew while the other elements were but ephemeral flies. There was no fanaticism, no foolishness, no scheming that did not flock to the young Christian communities and did not at least for a time and in isolated places find attentive ears and willing believers.

It sounds just like the American 1960s and 1970s, doesn’t it?

As a historian, Engels had the enormous virtue of moving outside the library, to understand early Christianity though his own lived experience in the nineteenth century radical Socialist underground. He knew exactly what it was like to operate in a clandestine transnational movement of the lower class. Both were under constant observation by the police, and you never knew exactly who might be a spy or informer.

Engels and The Early Christians

Oddly, given his strongly anti-religious opinions, Engels had something like a love for the early Christians, and he imagines talking to them as fellow-sufferers who came from exactly the same kind of setting. As he writes,

The history of early Christianity has notable points of resemblance with the modern working-class movement. Like the latter, Christianity was originally a movement of oppressed people: it first appeared as the religion of slaves and emancipated slaves, of poor people deprived of all rights, of peoples subjugated or dispersed by Rome. Both Christianity and the workers’ socialism preach forthcoming salvation from bondage and misery; Christianity places this salvation in a life beyond, after death, in heaven; socialism places it in this world, in a transformation of society. Both are persecuted and baited, their adherents are despised and made the objects of exclusive laws, the former as enemies of the human race, the latter as enemies of the state, enemies of religion, the family, social order.

Engels uses a quote from Ernest Renan: “If I wanted to give you an idea of the early Christian communities, I would tell you to look at a local section of the International Working Men’s Association.” [The so-called First International]

Hah! says Engels. What can a mere academic know about the everyday details of that kind of life?

I should like to see the old “International” who can read, for example, the so-called Second Epistle of Paul to the Corinthians without old-wounds re-opening, at least in one respect. The whole epistle, from chapter eight onwards, echoes the eternal, and oh! so well-known complaint: “les cotisations ne rentrent pas” — contributions are not coming in! How many of the most zealous propagandists of the [eighteen-]sixties would sympathizingly squeeze the hand of the author of that epistle, whoever he may be, and whisper: “So it was like that with you too!” We too — Corinthians were legion in our Association — can sing a song about contributions not coming in but tantalizing us as they floated elusively before our eyes.

More seriously, his comments on the turbulent early Christian world merit quotation:

In fact, the struggle against a world that at the beginning was superior in force, and at the same time against [amongst?] the innovators themselves, is common to the early Christians and the Socialists. Neither of these two great movements were made by leaders or prophets — although there are prophets enough among both of them — they are mass movements. And mass movements are bound to be confused at the beginning; confused because the thinking of the masses at first moves among contradictions, lack of clarity and lack of cohesion, and also because of the role that prophets still play in them at the beginning. This confusion is to be seen in the formation of numerous sects which right against one another with at least the same zeal as against the common external enemy.

So it was with early Christianity, so it was in the beginning of the socialist movement, no matter how much that worried the well-meaning worthies who preached unity where no unity was possible.

Beyond noting parallels and echoes, Engels is making the vital point that these were the ways that insurgent apocalyptic and millenarian movements tended to act, and the problems they tended to face – all the sectarianism, the credulity, and the cultish behavior. You don’t have to agree with every one of Engels’s comments and criticisms, but the whole piece is well worth reading, and indeed eye-opening, for reading the New Testament.

Ben Jones discussed Engels in his recent Apocalypse Without God : Apocalyptic thought, ideal politics, and the limits of Utopian hope (Cambridge University Press, 2022).

I am adapting this material from blogs published on this site many aeons ago.