The winter holidays are a time when Americans celebrate home and family. Consider the songs that are part of the season’s soundscape—“I’ll Be Home for Christmas,” for example, and “Home for the Holidays”—and the feel-good stories of family festivities that we admire and share on social media: all of these things are expressions of how family is central to the religious and secular rituals that mark this time of year, to the point that family time takes on a sacred significance of its own. Seeing family time as sacred is perhaps one of the few things that unite Americans. As Pew recently reported, a clear majority of Americans on both sides of the political aisle find meaning and fulfillment in spending time with family.

But what happens if you can’t be with your family during the holidays or during a significant life event? This experience is common for migrants, who are often forced to live apart from loved ones for significant periods of time due to government policies that limit movement across international borders. Refugees have a distinctive version of this experience, as they are forced to contend with not only the trauma of war and persecution in their countries of origin, but also the uncertainty of their future in the countries where they hope to resettle. The unpredictability of their lives means they endure a particularly painful form of family separation. The U.S. government might deny entrance to one refugee but then admit his two family members, one of whom might be resettled in Wisconsin and the other in Rhode Island. Gathering with relatives—during the holidays or at any other time of year—is thus impossible for many refugees, who often endure a long and cruel separation from their families and who wonder if they will ever see their sisters or fathers ever again.

As I argue in my forthcoming book, the family separation produced by American refugee policies can have important religious consequences. Because family is central to ritual life, government policies that interfere with the ability of families to gather together ultimately interfere with religious and spiritual life. For the Hmong refugees who are at the center of the story I tell, resettlement in the United States brought profound religious and spiritual unsettlement. Hmong refugees experienced significant religious changes in America in part because of government policies that made it difficult for Hmong families to come together to conduct traditional rituals with kin and community.

“Hmong is family”

For Hmong people, an ethnic group native to Southeast Asia and portions of Southwest China, the practice of traditional rituals has historically depended on the involvement of both the nuclear and extended family. Family is important to traditional Hmong spiritual life for several reasons. To begin, many rituals are related to lineage and clan and are based in the home. Family members are responsible for conducting important household rituals, such as maintaining a home altar dedicated to household spirits.

In addition, family elders are the traditional keepers of important ritual knowledge. The presence and expertise of elders ensures that Hmong families properly conduct rituals that ensure harmonious relations with the spirit world.

Finally, Hmong rituals can be lengthy and labor-intensive and often require the involvement and contributions of many people, especially kin and clan members. Yia, one Hmong American woman I interviewed in Saint Paul, explained that “in the old tradition, you have to have helping hands.” Yong Kaye, a Hmong American man who also lived in Saint Paul, said that the need for helping hands is why practitioners of traditional Hmong rituals must live among family and ethnic community. “[I]n our tradition, you just cannot do [rituals] on your own,” he said.

The overlap of Hmong family life, traditional ritual practices, and ethnic identity was summed up by the Hmong American father in Garden of the Soul, a play written and performed by a Hmong American theater in Saint Paul, Minnesota in 1995. The father, troubled by the social, cultural, and religious changes he observed in his family and community, decried the lack of spiritual unity within Hmong American families. “Hmong is family,” he declared. For him, bringing the family together to practice a shared set of ritual traditions was the essence of being Hmong.

American refugee policies and family separation

However, coming together as a family was often difficult in the 1970s and 1980s, when Hmong refugees first began to arrive in United States. These Hmong refugees, accepted for resettlement after having fought as the anti-communist allies of the United States during the “Secret War” in Laos, were subjected to American refugee policies that often separated families.

Hmong refugees sometimes found themselves split between continents. The United States had a preference system that prioritized Hmong refugees considered “high risk” because they had served in the military or had been employed by the U.S. government during the war. But Hmong refugees accepted for earlier resettlement sometimes had relatives who fell in different priority categories. As a result, they were forced to wait years before they could reunite with family members who had been left behind in the camps in Thailand.

Even in the United States, Hmong refugees were separated from one another. During the 1970s and 1980s, the government and voluntary agencies that planned and implemented the resettlement program intentionally dispersed refugees across the country. This “scatter policy” arose in part from a practical need to place refugee families in communities where there were available sponsors. Proponents of the scatter policy also argued that it would reduce the local economic impact of refugee resettlement and facilitate rapid cultural assimilation.

The social and cultural costs of these refugee policies were significant and borne most heavily by the people who were supposed to benefit most from resettlement: refugees themselves. As a result of these resettlement policies, Hmong families found themselves spread across the globe, with relatives in different cities, states, and countries. Living apart from their relatives and also from other Hmong people, Hmong refugees recounted feeling sad and isolated. Cher Vang, for example, recalled the frustration he and his family felt when they were resettled by a Lutheran church in Loganville, Wisconsin, a town of only a couple hundred people. “We came to a small town and we felt kind of lonely,” he said. “We say to our sponsors, ‘We cannot stay here, because there’s just five of us in the family.’”

Refugee resettlement and the unsettlement of Hmong ritual life

Having only five immediate family members and no other kin or community members was a significant hindrance to traditional Hmong ritual life. Because of American refugee policies, Hmong people in Cher Vang’s situation did not have the single most important resource necessary to continue Hmong spiritual practices: Hmong people. Without the “helping hands” of relatives, Hmong refugees found themselves uncertain about the future of traditional Hmong rituals. Elaborate events such as Hmong funerals—which typically lasted three full days and required many people to help conduct ceremonies, cook food, and prepare ritual spaces—seemed impossible to continue.

American refugee policies also unintentionally deprived Hmong refugees of elders and ritual experts whose knowledge was necessary for the proper practice of Hmong rituals. Many of the Hmong refugees who were given higher priority in the refugee admissions preference categories also happened to be younger people, a subset of the Hmong population that had comparatively less ritual knowledge, expertise, and experience. In contrast, the people who were typically the lowest priority and who were left behind in the refugee camps in Thailand were elders and ritual experts such as shamans—in other words, the people who were the Hmong community’s spiritual and cultural authorities. Jacque Lemoine, an anthropologist, noted that shamans were far less common in the United States in the early 1980s, in part because, as he put it, shamans “were excluded from the resettlement list as useless religious practitioners.”

The separation from family and the absence of ritual experts were two factors that created a ritual crisis for Hmong people in their early years in the United States. Although resettling in a new country had held the promise of greater security and freedom, Hmong refugees found themselves deeply unsettled by life in America, where some felt they lived with even less spiritual security and religious freedom than they had in Laos and Thailand. They struggled with the reality that it was difficult, and sometimes even impossible, to practice the rituals that had long sustained their spiritual wellbeing, and they worried about the future of their souls, as well as the fate of their Hmong beliefs, practices, and cultural identity.

For many Hmong people, the ritual crisis set in motion by American refugee policies were not theoretical or abstract concerns, but matters that could result in real, immediate, physical suffering. Because Hmong people have traditionally seen bodily well-being as connected to spiritual well-being, they worried, for example, about how they could remain well if they did not have access to a shaman. The concern was enough to convince some people to abandon traditional Hmong practices altogether. For example, Ong Vang Xiong, a Hmong woman living in the Twin Cities, ultimately made the decision to “believe in the new religion”—Christianity—for this reason. “I came to this country,” she said. “It was very hard to find a shaman, so it was very, very hard for me. That is why I went to believe in the new religion, so I do not have any more hard times.”

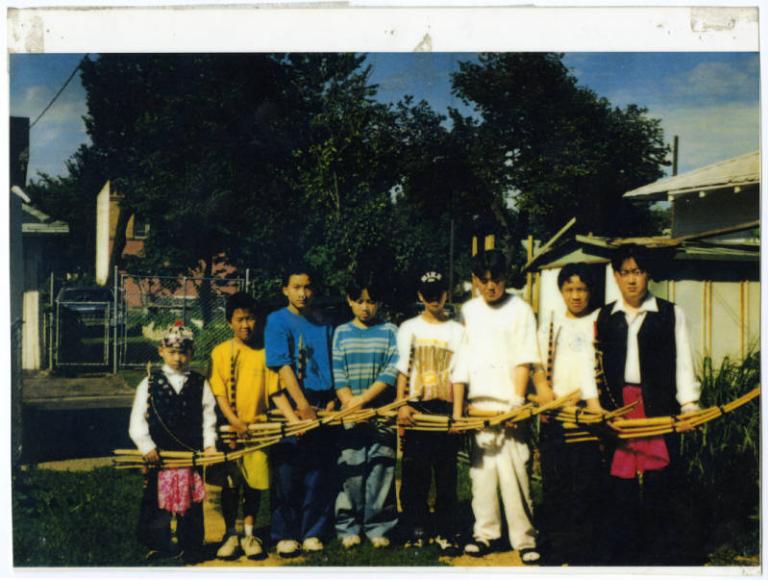

The hard times did not last forever. Over the past four and a half decades, Hmong refugees have been able to sponsor the resettlement of their relatives, rebuild their ethnic communities, and renew their practice of traditional rituals. They have established new Hmong American institutions that have helped them to continue Hmong rituals in an American setting. They have kept Hmong traditions alive through resilience, creativity, and change.

However, these developments have been possible also because of Hmong people’s intentional efforts to reunite with their relatives and undo the family separation created by American refugee policies. They did this because so much depended on being together again–not only the well-being of their families, but also the continuity of their ritual traditions. And here I return to the point I made at the beginning of this post: that family is central to ritual life. This is true for those of us who talk nostalgically about being home for the holidays. It is also true for Hmong refugees, who have been forced to contend not only with war and forced migration, but also with government refugee policies that imposed significant burdens on Hmong refugees’ spiritual and religious life, all while appearing to have nothing to do with religion at all.