Today we welcome a guest contribution from John T. Lowe, Ph.D.. Lowe teaches American History at the University of Louisville as a Senior Lecturer. His research focuses on the intersection of race and religion in early America. Follow @johntlowe on Twitter.

Today we welcome a guest contribution from John T. Lowe, Ph.D.. Lowe teaches American History at the University of Louisville as a Senior Lecturer. His research focuses on the intersection of race and religion in early America. Follow @johntlowe on Twitter.

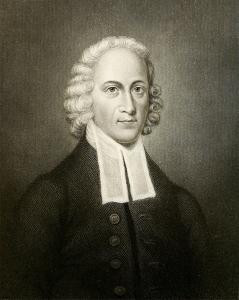

Over the past several decades, Jonathan Edwards has become the centerfold of American religious history. This should come to no surprise though. With research centers on every habitable continent in the world, and his completed works freely available online, Edwards has garnered attention from both the academy and laypeople alike.

And like many historical figures, unearthing their theology comes with troublesome views. Jonathan Edwards is no exception. Recently, popular media outlets have highlighted his enslaving as problematic corollary to the rest of his theology. It’s hard to imagine that the Evangelical titan of the Great Awakening would practice something so vile. Today, his participation in slavery and the slave trade have become well-known, however, rarely do his readers realize Edwards also contributed to abolitionist thought.

A few months ago, I (successfully) defended my dissertation The Practice that Prevails: Jonathan Edwards, Slavery, and Race. One of my discoveries was seeing how Edwards influenced his students and readers toward abolitionist thinking—Samuel Hopkins, his son Jonathan Edwards Jr., Joseph Bellamy, and Andrew Fuller to name a few. In no sense should we label Edwards an abolitionist or place him in antislavery circles. Not once did he call slavery a sin, nor did he call for abolitionism. Rather we should understand him as a transitional figure who supported American slavery as an institution, denounced the slave trade, but laid the theological groundwork for his readers to take up antislavery—and even emancipation—positions.

We must first understand something. Jonathan Edwards was an enslaver of Africans. He grew up in a home that had at least two enslaved people, and had several himself throughout his career. Even during his Stockbridge tenure toward the end of his life, Edwards had at least one enslaved African—“A negro boy named Titus.” Edwards never referred to slavery as a sin, nor had he manumitted his own slaves. He even openly defended another minister for owning an enslaved African. So, how did Edwards, who was staunchly pro-slavery, consequently influence his students to become abolitionists?

The New Divinity of the eighteenth and early nineteenth century relied heavily on Jonathan Edwards’s doctrine of disinterested benevolence. This doctrine is uninterested in the self and seeks to love and make choices based on the benefits of others. Part of the reason Edwards developed his idea of disinterested benevolence was because he was focused on the “nature of true religion,” or another way “what does it mean to be a true Christian?” Edwards would spend the rest of his life answering this question. However, in his Religious Affections, he summed it up that “The Scriptures do represent true religion, as being summarily comprehended in love.”

Edwards defines his version of love, or benevolence, later in his Charity & Its Fruits. Using 1 Corinthians 13:1–3, Edwards determined that “love, or that disposition or affection whereby one is dear to another; and the original (ἀγάπη), which is here translated “charity,” might better have been rendered “love.” For Edwards, true Christian love should be “exercised towards God or our fellow-creatures” and not be concerned with selfish interests that would feed into one’s own sin.

But if Edwards enslaved Africans, how did he influence his followers to become abolitionists? His student and close friend, Samuel Hopkins, used the doctrine of disinterested benevolence to call for ending slavery, as an oppressive bondage that was counter-productive to the spread of Christianity. Hopkins’s True Holiness mirrored much of Edwards’s own theology. He agreed with Edwards’s doctrine, but Hopkins applied love in the sense of liberating enslaved people from their social status. This in turn would make Africans less bitter toward the gospel. Edwards and Hopkins both longed for revival and outpourings of the Spirit among unconverted peoples. Slavery, at least for Hopkins, hindered revival.

Toward the middle and late eighteenth century, Newport, Rhode Island had become an epicenter for the slave trade, a hub for human-trafficking. A resident of Newport, Hopkins “often looked upon the cargoes of Africans who were landed at the wharves near his meeting-house and parsonage.” He witnessed first-hand the brutal treatment of enslaved Africans arriving on the North American East coast. This was not the Christian-love he learned from Jonathan Edwards.

Hopkins’s interpretation of Edwards would cause him to favor abolitionism. “The following precept of our Lord and Savior,” Hopkins boasted, “‘All things whatsoever ye would that men should do unto you, do ye even so to them,’ which is included in loving our neighbor as ourselves, will set at liberty every slave.” The “Golden Rule” summarized disinterested benevolence. Hopkins believed that if Christians wanted to express true religion, or real love, they would put a halt to the slave trade and free every enslaved African across the nation.

Hopkins went where Edwards did not. He was willing to apply disinterested benevolence even if it meant rearranging the social-hierarchy or bringing about radical social reform in ways that were foreign to Edwards. As a side note, we can see how oncoming Enlightenment ideas of revolution, individuality, populism, freedom, and the like were taking form in Hopkins that had not formed in the British Edwards.

Readers of Edwards will be shocked to learn there is nothing in his writings that suggest his defense of institutional slavery was racially motivated. His Draft Letter on Slavery does not reveal that pro-slavery views were because of racial superiority. That is not to say he was not racist, nor harbored ethnocentric views toward non-Whites. He definitely had negative tones toward Native Americans, but did not refer to Africans in such a way. But it shows that Edwards’s views on slavery are more complex than his puritan predecessors such as Cotton Mather, Morgan Godwyn, or Samuel Sewall.

For Edwards, defending slavery as an institution was defending a God ordained hierarchy. Unlike him, Hopkins felt that a true Christian love would be interested in alleviating enslaved Africans from harsh treatment. Edwards might not have agreed with Hopkins’s application decades after his death, but he is still responsible for instilling a love that would call for abolition.