Today we welcome back Allie Roberts as a guest contributor to the Anxious Bench. Roberts is a PhD student in the History department at Baylor University. Her research focuses on Black women’s leadership and grassroots activism during the twentieth century, particularly during the US civil rights movement.

History goes blind and in darkness,

neither sees nor is seen, nor is

known except as a carrion

marked with unintelligible wounds;

dragging its dead body, living,

yet to be born, it moves heavily

to its glories. It tramples the little towns,

forgets their names.

– Wendell Berry

Winding backroads and rolling hills weave their way through the South. Every time I drive home, tracing familiar paths through Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi back to Alabama, I pass through small town after small town. On a recent drive, I listened to award-winning author Imani Perry’s South to America on audiobook. Perry’s prose captivates, and her reflections on the significance of the South to the history of the United States reminded me of how personal, often local, stories remain crucial to understanding the past and present.

Take the history of the civil rights movement, for example. Familiar narratives of the civil rights movement highlight national stories and renowned figures, such as the 1963 March on Washington and Martin Luther King, Jr. While such events and people are undoubtedly important, this practice of centering only prominent events, places, and people distorts our understanding of the civil rights movement and the long Black freedom struggle.

Some historians of the civil rights movement emphasize the significance of local people and local activism. These regional histories focus readers on a specific time and place, both complicating and broadening historical perspectives. Local accounts of the civil rights movement remind us of the complexities, hardships, and resilience of everyday people in everyday places.

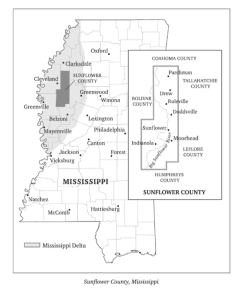

Several books about local civil rights movements, often complete with county maps to situate the reader in the southern landscape, not only complicate but sometimes challenge widely held narratives about the movement as a whole. These scholars reveal local oppression and local resistance in the small-town South, and as a result, they provide narratives comprised of complex people in rural places whose stories tell us more about the civil rights movement, the South, and the United States.

John Dittmer’s Local People (1994) focuses on the Mississippi Delta, tracing how organizational partnerships with locals shaped the movement there from post-World War II to the late 1960s. Dittmer’s explorations emphasize the work of local Mississippians who, as SNCC activist Charles McLaurin remembered it, were “…the true leaders. We need only to move them, to show them. Then watch and learn.” Organizations like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) sent activists from across the country to partner with locals and promote voting rights, better schools, economic justice, and racial equality. While Dittmer does emphasize these grassroots partnerships, he primarily focuses on connecting local movements in Mississippi to a broader civil rights narrative. At times, local leaders are overshadowed by well-known civil rights figures. Still, he asserts that activists, Americans, and those who care about justice have much to learn from the local people who pushed for a liberated state and ultimately, a democratic nation.

In Let the People Decide (2004), J. Todd Moye provides further insight into local Mississippi movements as he centers activism in Sunflower County. Moye traces three different civil rights movements from 1945–1986 in Sunflower County, Mississippi. Comprised of a small number of middle-class Black Americans, the first movement pushed for the implementation of Brown v Board. In the mid-1960s, Moye examines the second movement as a poor people’s campaign promoted by locals and grassroots organizations, such as SNCC and the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO). He characterizes this period as a human rights movement that sought economic justice, educational opportunities, and voting rights. Lastly, in the 1980s, the third movement pushed for better leadership in Indianola’s public school system and transcended class boundaries. Local groups, such as Concerned Citizens (not to be confused with Citizens Councils), sought to elect progressive school board members. In each phase, activists faced unrelenting resistance from white people in Sunflower County. Still, Black locals and activists pursued creative, homegrown solutions as they sought justice in their community.

Susan Youngblood Ashmore analyzes the Alabama Black Belt and local advocacy for federal poverty relief programs in Carry It On (2008). For local activists, the Black freedom struggle and the fight against poverty remained intertwined. Ashmore recognizes the importance of federal involvement as well as grassroots activism as both sought to address the needs of Alabama’s poor. She especially emphasizes organizational work in the Black Belt, particularly among agricultural workers. Farmers in the Southwest Alabama Farmers Cooperative Association (SWAFCA), for example, organized, advocated for federal funding, and resisted oppression from local government officials. Through her analysis of the federal, state, and local, Ashmore reveals that scholars cannot readily separate economic activism from racial justice initiatives in the civil rights movement. For poor Black people in Alabama, such efforts remained inextricably joined.

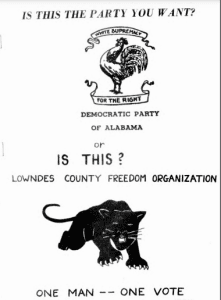

Lastly, Hasan Kwame Jeffries’s Bloody Lowndes (2009), recently developed into the documentary Lowndes County and the Road to Black Power, examines freedom rights activism and the rise of Black Power in Lowndes County, Alabama. Also centering the Alabama Black Belt, Jeffries’s Bloody Lowndes offers unique insight into how local politics and social mores shaped Black activism and resistance. Beginning in 1965, activists in the Lowndes movement agitated for voting rights, economic and educational opportunities, and county government positions. SNCC activists organized local people who were already resisting white supremacy and cultivated a cohesive, though never fully unified, countywide movement. Under the auspices of the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO), locals requested intervention from the federal government to aid farmers and address voter suppression, and together, the LCFO and SNCC established the Lowndes County Freedom Party (LCFP), whose black panther symbol directly contradicted the Democrats’ white rooster. Though SNCC’s withdrawal from the region in 1966 resulted in a dearth of fulltime grassroots organizers, Lowndes County locals remained committed to freedom politics.

These examinations complicate broad sweeping analyses of the civil rights movement and challenge us to consider how at different times and in different places, oppression and resistance unfolded in particular ways. They also resist narratives of the civil rights movement that only represent progress and the realized pursuit of an equal democracy. National narratives that conclude with the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and 1965 Voting Rights Act ignore how oppression and resistance persist in Mississippi, Alabama, throughout the South, and across the nation. The fight for justice at the grassroots wages on, as in recent advocacy for clean water in Mississippi and for a political voice in rural Alabama.

As Imani Perry writes, the “consequence of truncating the South and relegating it to a backwards corner is a misapprehension of its power in American history” (13). These stories of local oppression and resistance are national stories. To understand the country, then, we must pay attention to the South and to the little towns. We must remember their names.