As an immigrant and Afro-Brazilian historian with a profound interest in the history of Christianity in the United States, I have been thinking about potential intersections between U.S. Black Church history and World Christianity. How race is imagined and discussed in U.S. Church History circles remains flagrantly limited to African American/White paradigms. I wonder if continuing to trace connections between U.S. Black Church history and World Christianity can help construct historical narratives that complexify the often-simplistic way race is framed in U.S. Church History circles and open spaces for more vigorous forms of racial and ethnic solidarity across the Américas. So, my next two posts will offer brief, tentative reflections on the potential value of articulating connections between the histories of U.S. and Latin American Christianities. My hope is that tracing such connections can give us additional avenues from which to imagine how conversations between U.S. Black Church History and World Christianity can, to quote David D. Daniels III, “spark our impoverished historical imagination” and “complexify the concept of race to strengthen multi-racial solidarity.”[1]

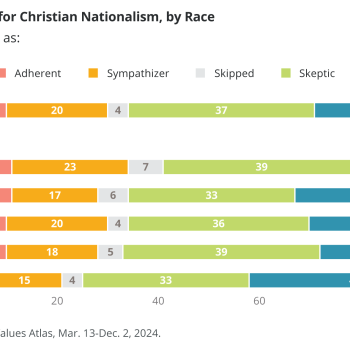

Daniels’s work building on Black North Atlantic Christianity has been an important move toward pushing boundaries and complexifying the notion of “the Christian West.”[2] This approach of redrawing maps and narrating cross-regional connections that aim to expand racial and ethnic solidarity is essential in general. However, such move is particularly important considering demographic projections which suggest that, by 2060, the U.S. population will be 9% Asian, 15% Black or A.A., and 30% Latinx (a number that includes many Latin American immigrants and their children). The work of strengthening narratives that connect the U.S. Black Church and the church in Latin America seems crucial for justice-seeking Christianity but also because of the strategic value of strengthening racial and ethnic solidarity during such significant demographic shifts.[3]

I am not a theorist, neither am I a historian whose work focuses primarily on U.S. Black Church history. However, researching U.S.-Latin American connections from the vantage point of the history of Christianity, both in terms of U.S. presence in Latin America and of Latin American immigration to the U.S., helped me notice connections that may help us continue to imagine different ways in which the intersecting trajectories of race, ethnicity, religion, and migration can be creatively explored.[4] I agree with scholars who argue that race and ethnic identities are, among other things, sets of contested stories that individuals and groups tell about themselves and others. Identity-making is, from this prism, also narrative-making or storytelling. And as such, history is central for any project that aims to image a reconfiguration of these identities.[5]

In terms of Latin American Christianity, I am particularly interested in the history of Brazilian Protestantism—and its relationship to race, missions from the U.S. to Brazil, and migration from Brazil to the U.S. I think that the Brazilian entry point offers an instrumental case study that touch on central aspects of this crucial conversation for several reasons. I will mention two of these significant reasons. First, Brazil can be considered the country with the largest number of Afro-descendants in the world. The Brazilian Black and Brown population in 2019—the overwhelming majority of them with significant African heritage—was around 110 million.[6] Because of how Brazilian racial imagination developed, not all of those individuals emphasize their African heritage.[7] As Henry Louis Gates popularized in his PBS series “Black in Latin America,” there are over 136 unofficial racial categories in Brazil, and racial and ethnic categories are highly contested in the Brazilian context.[8] However, Afro-Brazilian movements are growing in strength and popularity. The official categorization and racial self-understanding of Afro-Brazilians will likely continue to shift to include a more robust emphasis on Afro-descendance. Movements of “consciência negra” (Black consciousness) continue to work towards educating Afro-Brazilians to recognize their African roots and celebrate them.[9] Insofar as racial and ethnic identities are also a set of shared stories and memories, this work of conscientization opens room for new stories about who Brazilians with African heritage believe they were, are, and can be.

The histories of the U.S. Black Church and Brazilian Protestantism have points of contact that could be fruitful for constructing a hemispheric Afro-descendant Christianity. These points of contact can be revealed in at least two ways: 1-via stories of Black religiously informed resistance in Latin America that resemble moments in the histories of the U.S. Black Church and, perhaps paradoxically, 2-by revealing overlaps between the religiously informed White supremacies that also connect religious communities across the hemisphere. I will reflect on those in my next post.

[1] Quoted from the “Being Black and Christian in America: The Black Church and New Vistas of Race in the U.S.” panel, in which I responded to David D. Daniels III’s presentation. See here for more: https://aviary.ecds.emory.edu/collections/1305/collection_resources/40067

[2] David Daniels III, “Reterritorizing the West in World Christianity: Black North Atlantic Christianity and the Edinburgh Conferences of 1910 and 2010,” Journal of World Christianity 5, no. 1 (2012): 102–23.

[3] Jonathan Vespa, David M. Armstrong, and Lauren Medina, “Demographic Turning Points for the United States,” The United States Census Bureau, accessed April 7th, 2021, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2020/demo/p25-1144.html.

[4] For examples, see João B. Chaves, Migrational Religion: Context and Creativity in the Latinx Diaspora (Waco: Baylor University Press, 2021); João B. Chaves, O Racismo Na História Batista Brasileira (Brasília: Novos Diálogos, 2021); Joao Chaves and C. Douglas Weaver, “Baptists and Their Polarizing Ways: Transnational Polarization between Southern Baptist Missionaries and Brazilian Baptists,” Review & Expositor 116, no. 2 (2019): 160–74; Joao B. Chaves, Evangelicals and Liberation Revisited (Eugene: Wipf and Stock, 2013).

[5] For a recent manuscript that considers the role of religious and national mythologies in the construction of ethnic identities see Jonathan E. Calvillo, The Saints of Santa Ana: Faith and Ethnicity in a Mexican Majority City (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

[6] Bloomberg recently focused on this statistic, pointing out the drastic underrepresentation of Black leadership in the Brazilian market. See Cristiane Lucchesi and Felipe Marques, “Brazil Has 109 Million Black People. Not One Runs a Big Bank,” Bloomberg.Com, accessed May 1, 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-07-17/brazil-has-109-million-black-people-not-one-runs-a-big-bank.

[7] Edward E. Telles, Race in Another America: The Significance of Skin Color in Brazil (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), 1–2.

[8] Henry Louis Gates, Black in Latin America | Brazil: A Racial Paradise? | Episode 3, https://www.pbs.org/video/black-in-latin-america-brazil-a-racial-paradise/.

[9] See Vítor Miranda, “A Resurgence of Black Identity in Brazil? Evidence from an Analysis of Recent Censuses,” Demographic Research 32, no. 59 (2015): 1603–30; Allan Charles Dawson, In Light of Africa: Globalizing Blackness in Northeast Brazil (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014); and Tianna S. Paschel, Becoming Black Political Subjects: Movements and Ethno-Racial Rights in Colombia and Brazil (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016).