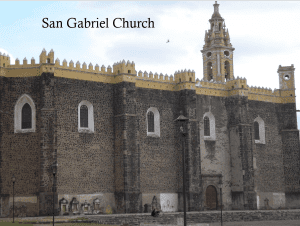

May my body be buried in the Church of San Gabriel in the said

city of Cholula in the tomb that the father guardian or president of

the said convento will indicate to me…. Bury me in the habit of the

blessed one, San Francisco; it is for the said effect that I ask it.

– doña María Tlaltecayoa, 1596

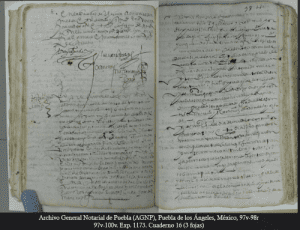

(Archivo de Notarías, Puebla, Cuaderno 18, No. 1276, folio 8r. Full doc: folio 7r-9v)

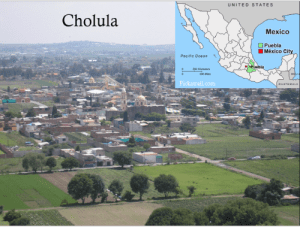

During my first summer researching in Mexico as a UCLA doctoral student, I came across a collection of twenty-five Spanish-language wills from 1590s Cholula at the Notarial Archive in Puebla de los Ángeles. In the usual mix of Castilian men and women was María de la Paz, a wealthy immigrant obrajera (textile mill owner), a Portuguese youth, and several native people, the most significant being doña María Tlaltecayoa, an india principal – a high-ranking native woman whose lineage dated to the pre-contact period – married to Juan Cardoso, a Castilian labrador, or low-ranking Spanish farmer who owned lands and the right to native labor to work it.

Last Will and Testament of María de la Paz, 23 October 1595

Last Will and Testament of María de la Paz, 23 October 1595

On May 23, 1596, several colonial officials crowded around the prone figure of doña María Tlaltecayoa, who lay on her death bed in her home on the marshy boundaries of Cholula’s jurisdiction. In addition to the notary, the alguacil mayor (high-ranking officer in the cabildo, or town council) and a Nahuatl interpreter were present to assist doña María in the execution of her last will and testament. Native to Cholula, she was the legitimate daughter of Diego Tlaltecayoa and his legitimate wife, Isabel Tlapapaltze, indigenous leaders native-born to Cholula, and the legitimate wife of Juan Cardoso. A member of the Confraternity of the Most Holy Sacrament, doña María requested that the cofradía oversee her interment in the Franciscan Church of San Gabriel, leaving 10 pesos in alms to the convento to cover her funeral procession, burial, an unspecified number of open casket masses, and a Franciscan habit. Of all her requests, only the last appears unusual. A married lay woman, doña María did not have an official affiliation with the Franciscans (she did not mention being Third Order). Why request a friar’s garb? To wear it to her grave. The pious practice of requesting burial dressed in the robes of a Franciscan – or indeed the habit of any religious order – originated in medieval Europe. By the sixteenth century, testators in Spain made wide recourse to this devout custom in their wills, as Carlos Eire outlines in From Madrid to Purgatory: The Art and Craft of Dying in Sixteenth-Century Spain. Like other aspects of Mediterranean Christianity, this pious custom traveled to colonial Mexico. What did it mean? What would prompt a lay person to request burial in a religious habit, why would friars accommodate this request, and what does this request reveal about attitudes toward death and the afterlife?

The pious practice of requesting burial dressed in the robes of a Franciscan – or indeed the habit of any religious order – originated in medieval Europe. By the sixteenth century, testators in Spain made wide recourse to this devout custom in their wills, as Carlos Eire outlines in From Madrid to Purgatory: The Art and Craft of Dying in Sixteenth-Century Spain. Like other aspects of Mediterranean Christianity, this pious custom traveled to colonial Mexico. What did it mean? What would prompt a lay person to request burial in a religious habit, why would friars accommodate this request, and what does this request reveal about attitudes toward death and the afterlife?

In early modern Spain, dictating one’s will while in good health was lauded as more meritorious than waiting for a final illness, not only for being a recognition of one’s mortality, but also an acknowledgement that one’s life and possessions were on loan from God. The act of writing one’s will in sixteenth-century Spain was, in fact, just one aspect of a highly ritualized process dating to the medieval period. When death appeared imminent, family and friends gathered to recite prayers or read aloud devotional material. Confraternity members often prayed for the sick person’s soul. A notary and a priest would be summoned to the home. After the priest heard the individual’s final confession and administered the last rites, the notary would sit bedside to record the last will and testament, a document believed not only to aid in the achievement of a good and holy death, but that could also mitigate one’s stay in purgatory, serving as a “passport to the afterlife” (Eire, From Madrid to Purgatory, 33-34). In this way, the notary – who served a political rather than a religious purpose – was drawn into the intimacy of the death ritual.

By the late sixteenth-century, the Franciscans were the only priests in Cholula, as there was no diocesan church until 1640 and no other religious order settled there, even to this day. The priest summoned for last rites would have been Franciscan, and burial in a Franciscan church would have been the only option for these testators. At the time these wills were composed – that is, the 1590s – Cholula was a thriving Franciscan center with over 25 friars in residence (see Gabriel de Rojas, “Relación de Cholula” [1585] Revista mexicana de estudios históricos 1, 1927). Founded in late 1528, the Franciscan establishment remained a simple collection of buildings for over a decade until native artisans completed an imposing church dedicated to the archangel Gabriel alongside the friary in 1552. With funding from the Crown and per Spanish custom, the new evangelization complex was deliberately placed on the site of the Quetzalcoatl Sanctuary using stones from the razed structure, capitalizing on Cholula’s pre-hispanic status as a Mesoamerican holy site and center of pilgrimage and political legitimization.

Prior to Spanish arrival, Cholula – or Cholollan, as it was known – was a flourishing indigenous altepetl (Mesoamerican city-state), pilgrimage site, marketplace, and center of learning, with a population ranging from 40,000-100,000 families (see Peter Gerhard, A Guide to the Historical Geography of New Spain, Revised Edition, 115). Due to a series of epidemics in the mid-sixteenth century, by 1585 the population had dwindled to about 9,000 vecinos or citizens (Gerhard, 115 and Gabriel de Rojas). Two of those epidemics occurred during the 1590s, the period of the production of these Cholula wills, though since I have so few wills it’s difficult to cite a correlation. What we do know is that by the late sixteenth century, the Franciscans in their habits would have been recognizable figures in regular contact with Cholula’s vecinos, both European and indigenous. Even though the Franciscans had settled in Cholula to Christianize the native peoples, their castle-like Convento de San Gabriel was the principal religious structure in town and accessible to everyone.

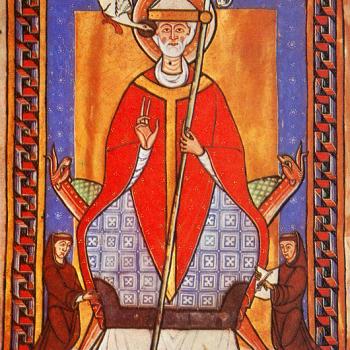

Twenty-two of the twenty-five testators in my collection request interment in the Franciscan habit, a tradition dating to medieval Europe when the mendicants gained prominence due to the popularity of two new orders – the Franciscans and Dominicans. According to early medieval monastic practice, one’s habit (or cowl) served as a physical manifestation of one’s vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, as well as an external sign of humility. The thirteenth-century Dominican, St. Thomas Aquinas, even believed that one’s habit was akin to a sacramental and in fact represented a second baptism (Eire, 109). In addition, in Bonaventure’s Life of Francis from 1260, he recounts a story about how the saint desired to die naked in order to fully embrace the humility and poverty of Christ. One of his companions, however – being inspired by God – convinced him to accept a habit as a loan, and Francis was thus able to enter heaven properly attired (Eire, 110). Taken together, these beliefs and pious stories led to the popular medieval belief that dying in a monastic habit meant preferential treatment in heaven.

Like requesting a religious habit as burial dress, requesting burial in a church attached to a religious order is also a tradition from Early Modern Spain. Because the only acceptable place of burial for Catholics was in consecrated ground, parish churches, monastery chapels, and cloisters became burial grounds. In this way, the vaults beneath parish churches became virtual cities of the dead. Early Modern Spanish priests recognized the profound psychological impact of surrounding parishioners with the buried dead to encourage their flock to ponder their own mortality. Because Cholula did not have a secular church until 1640, the Franciscan church of San Gabriel became the prime burial location for the city’s Catholics. Three testators request interment in San Andrés, which is the smaller Franciscan convento located in the nearby municipio of San Andrés Cholula, which became independent about 1585, that is, shortly before the composition of these wills.

Cord with three knots representing mendicant vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience

Cord with three knots representing mendicant vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience

Why would friars accommodate the request for burial in their religious habits? The simple answer is that the alms accompanying these requests provided supplemental income, because a bona fide habit could only be provided by the friars themselves. What does the request to be buried in a Franciscan habit reveal about attitudes towards death and the afterlife? For one, it indicates the persistence of the belief that wearing a religious habit upon one’s death would mean preferential treatment in heaven. But in order for that preferential treatment to take effect, the testators must believe that they would arrive at the gates of heaven wearing their religious habits. Or – at the very least – that God could, and would, look down into their coffins, see their burial dress, and grant them admission into heaven accordingly. Carlos Eire discusses these ideas in detail in the first section of his book.

In addition, by choosing the habit of the saint rather than of the order, testators are selecting St. Francis as their personal advocate in the heavenly court. With Christ sitting as judge on Judgment Day, having Francis – Christ’s beloved representative – as your defense attorney could only work in your favor. In this way, the Franciscan habit served to spiritually cloak the personal sins of the individual. Lying in the throes of their final illness and unable to avoid the inevitability of death, Cholula’s residents arranged their business affairs on earth so that their souls might expire in peace. To ensure a holy death and to increase their chances of avoiding eternal damnation or the fires of purgatory, these testators requested not only the customary requiem masses, but also the habit of St. Francis as their burial shroud. Functioning as a remedy both physical and spiritual, this garment’s power transcended this world, leading pious souls to the beatific vision in the next. Even today, pious Catholics in Cholula continue to request burial in a Franciscan habit.

Did this pious practice mean something different to doña María Tlaltecayoa, india principal? It’s difficult to say, since the friars had been in Cholula for over sixty years and it’s unlikely that she had known life without Christianity. Even so, she may have been familiar with pre-conquest funeral rites, which continued surreptitiously, including a ceremony known in Nahuatl as miccaquimiloa, that is, the “shrouding of the corpse,” during which a body was wrapped in various layers of ritual vestments to protect the soul from the itzehecameh or bitter flint-winds in Mictlan, the Nahua underworld. Native peoples also developed their own tradition of testament-writing in the alphabetic Nahuatl they learned from the friars. Doña María is an interesting case bridging two traditions. But alas, that is a post for another day.