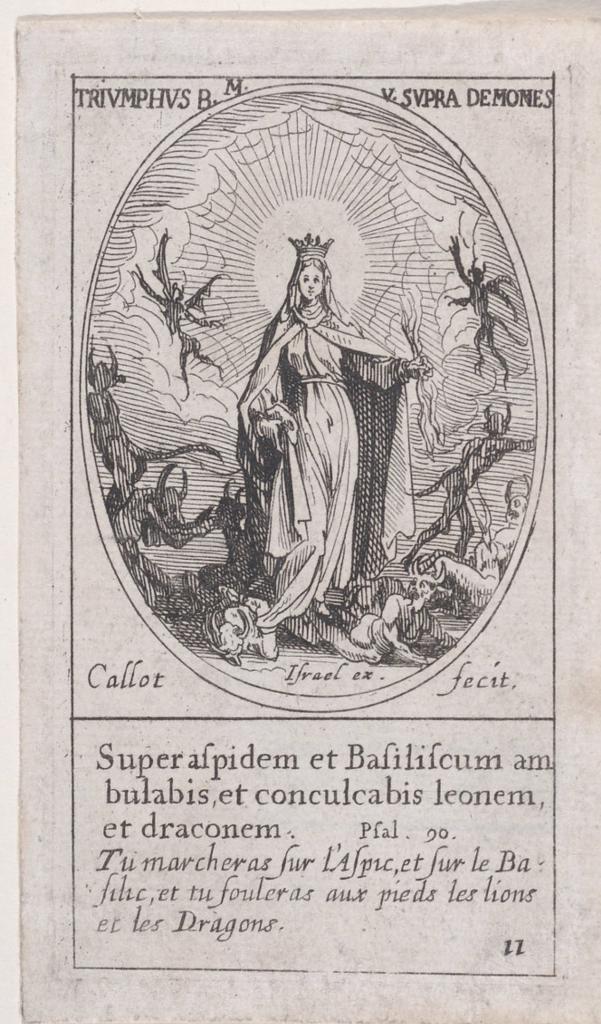

This is about a specific piece of art that powerfully illustrates the influence and reception of the Bible in Christian culture. It also gets to a much larger point about why we need to do a better job of incorporating the diverse aspects of that tradition, especially from Catholics, but also Orthodox.

My new book is a “biography” of the many lives of Psalm 91, a vastly influential and much referenced text in Christian history. One of the most quoted lines of that psalm is its verse 13:

Thou shalt tread upon the lion and adder: the young lion and the dragon shalt thou trample under feet.

which in the Latin Vulgate reads

Super aspidem et basiliscum ambulabis, et conculcabis leonem et draconem.

For the present, ignore the fact that the exact list of beasts varies between translations. This has widely been taken as granting the power to tread down demonic forces, which were commonly identified with political and religious enemies. Seriously, I can’t stress just how much that has been used, in political theory as much as exorcism, and in attempts to safeguard against plague and pestilence. You could write a whole book on the reception history of that one verse (although I don’t propose to do so).

One of the finest artistic examples (and there are many) comes from Munich, in Bavaria. In the seventeenth century, the Catholic duchy of Bavaria was a thriving center of European culture and art, as well as a key player in the political and military affairs of the day. During the Thirty Years War, Bavaria faced a deadly threat from the forces of Protestant Sweden, which occupied its capital city of Munich in 1632: plague struck the city in 1634 and again in 1636. When the grueling crisis had passed, Bavaria’s Duke erected a monument in the heart of Munich to thank the Virgin Mary for the city’s deliverance. Dedicated in 1638, that “Mary Column,” the Mariensäule, is still a proud Munich landmark, and one of the glories of European Baroque sculpture. It gave its name to the Marienplatz, the historic square in the city’s center.

The Mariensäule is an explicit invocation of Psalm 91. Surrounding the column on which now stands a golden statue of Mary are four figures of armored putti, each fighting and trampling a monstrous symbolic beast: the lion, dragon, basilisk, and serpent. These probably represent the evils of, respectively, paganism, heresy, schism, and Judaism, although a case can be made for the figures representing other menaces, such as war, hunger, pestilence, and heresy. Lest any observer be so religiously obtuse as to miss the scriptural origin, the putti’s shields each bear a phrase from the psalm – et basiliscum, et leonem, and so on. The Munich column, with its attendant warriors, inspired other spectacular examples in Vienna and Prague, and many lesser imitators. The Munich column is very well known in studies of Baroque art.

As in medieval times, Psalm 91 still asserted the triumph of the church and of faithful monarchs against their enemies. Nor was there anything new about depicting fellow Christians as monstrous beasts to be subjugated. What was distinctive about that era was the strong association that now existed between that psalm and the Virgin Mary. For Catholics, it became a thoroughly Marian Psalm, a theme massively reflected in all the arts.

But here is the point. The literature on Psalms is very large, but strikingly few of the commentators tend to pick up such post-medieval Catholic-rooted examples, which were heavily Marian in emphasis. That is true of Protestant scholars, but also of modern Catholics living in an age where Marian teachings and imagery are far less common than they were just a couple of generations ago. That neglect applies to 91, but also to the comparable accounts of many other psalms, and Biblical passages, although the available resources are beyond immense. Patristic and Medieval traditions are very well covered, but not those from the very substantial part of the Christian world that remained Catholic from the sixteenth century onward, and which, numerically, never ceased to a serious majority of the world’s believing Christians.

The same point is true not just of Psalms but of much of the Old Testament, and especially the prophetic books. Fearing charges of supersessionism, some Christians are nervous about mining the Old Testament for foreshadowings of Jesus, but throughout the centuries, it is often Mary who has attracted such a quest for veiled prophecies. If we try to understand Christian interpretation of the Old Testament over the past half millennium or so without paying proper attention to that Marian focus , we are making a grave error (and don’t get me started on the New Testament). If we write about those exegetical traditions from Protestant views alone – however broadly we range across Lutheran, Calvinist, and Anglican authors – we are missing the large majority of the literature that people actually produced and read at the time.

My takeaway is that histories of Christianity all too often focus on Protestant aspects and interpretations, leaving a great deal that remains to be said. The research opportunities are just enormous.