It’s fair to say that most Christians are respectfully aware of the Talmud as something that exists somewhere out there, and they know that it has a sacred quality for Jews, but is not something that they themselves are likely to approach – nor do they have any great idea what it might contain. The same is true of the larger body of rabbinic writing and scholarship – the Mishnah, Midrashic interpretations, legal Halakhah, mystical Qabala, This post is not only to suggest some of the treasures that can be found there, but also to point to an invaluable online resource for doing so. I stress immediately that I am primarily writing for Christians, who might find at least some of what I have to say novel or surprising!

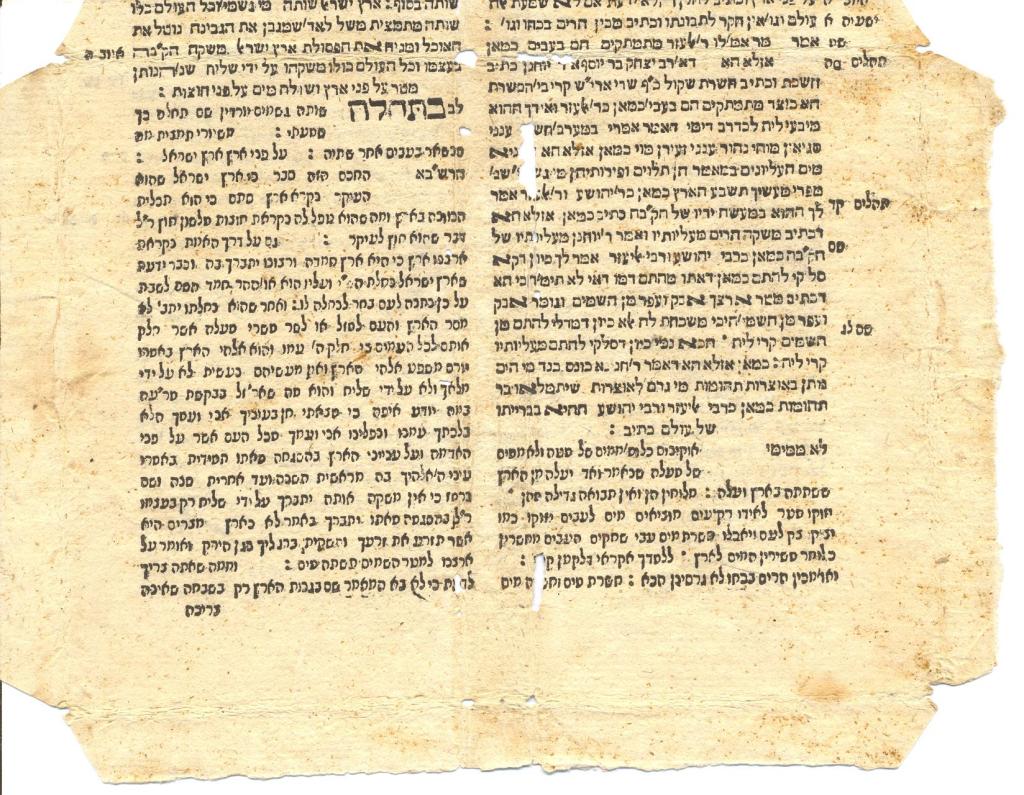

In my recent book on the many lives of Psalm 91, He Will Save You from the Deadly Pestilence, I naturally used such resources to examine how Jews had understood that text, about which they wrote a great deal. I will cite one example that I find truly evocative. In the sixth century AD, Jewish scholars in Babylonia, ancient Iraq, compiled a collection of legal and ritual decisions that were collectively known as “instruction,” or Talmud. Despite their relatively late date, these texts included much authentic material dating back to the time before the destruction of the Second Temple four centuries before, traced through a series of authorities.

One of these tractates, known as Shevuot or “Oaths,” hauntingly recalls the consecration of an addition to the old Temple’s courtyard, and the music that accompanied it, with harps, lyres, and cymbals. Drawing on the Mishnah, it records that after the psalms of thanksgiving and celebration, the clerical choirs sang Psalm 91, remembered as “the Song of Evil Spirits, which begins: ‘He that dwells in the secret place of the Most High.’ And some say that this psalm is called the Song of Plagues.” “The Song of Evil Spirits” is shir shel pega’im, and changing one letter makes it “the Song of Plagues,” nega’im, suggesting the dual purposes for which it was employed. It was meant both to fight demons, and to protect against plagues and disease.

Think about that. What we have here is a direct recollection of a scene in the Temple when it still stood, in – shall we say – 50 or 60 AD, when St Paul might have been visiting the building, and when the Essene house at Qumran was still operating. Further, we now appreciate the special connection that the Psalm had with the Temple. Now remember the scene in Luke 4 which Satan confronts Jesus in the Wilderness, and puts him at the pinnacle of the Temple. Throw yourself down, he says, and he actually quotes Psalm 91 – angels will lift you up in their hands, so that you will not strike your foot against a stone. What could be a more appropriate text in that time and place?

Before I proceed further, let me turn to the resource I mentioned for finding such material. Once you have a citation (and fine indexes are easily available) you can then go online to the user-friendly sefaria.org, “the largest free library of Jewish texts available to read online in Hebrew and English.” For instance, the line I quoted earlier can be found here, where you find both Hebrew text and English translation, together with access to multiple commentaries. Sefaria’s wonderful library includes all the major kinds of text available – the Bible, of course, the Tanakh, but also the rabbinic material I listed earlier, drawn from multiple translations, and all introduced with helpful guides. It’s a treasure house, and you can dip and browse until the last syllable of recorded time. You can get a Sefaria app for your IPad. (The site takes donations: they are an excellent cause to support!)

I offer a screenshot of the main offerings – the links are not live, but just go here for the real thing:

Pro tip: there are two Talmud versions, the Jerusalem (Yerushalmi) and Babylonian (Bavli). The two have some tractates with the same name, but which are utterly different in their content: Eruvin is an example. Citations will specify which version is meant with a letter y or b, so you know whether to look for y. Eruvin (Yerushalmi) or b. Eruvin (Bavli). Trust me, knowing those little letters saves you precious time in hunting down citations.

A World of Spirits, Demons, and Angels

Using such resources, I traced the history of Psalm 91 as it was interpreted by those rabbis, and the journey was fascinating. Much of the literature concerns what Christians call spiritual warfare, because, as Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi observed around 240AD, “the entire world is filled with spirits and demons.” Or to take another comment, “There is not a piece of ground which supports one roba of seed, in any part of the world, that does not contain nine hundred kabs of demons.” We do not have to translate the quantities too exactly to grasp the point that demons were ubiquitous and threatening.

Let me say right away that I don’t wish to suggest that such concerns are in any way central to Talmudic texts, which cover an inconceivably broad range of issues and topics: this just happens to be what I was working on at this particular time.

You can actually reconstruct a whole demonology from those rabbinic exchanges over 91. In reading the psalm, the sages regularly gave personal identity to the terms and concepts listed there, and then let their imaginations run free in describing what these monstrous creatures might actually look like and how they would behave. One popular use of personification was qeteb (ketev), or Destruction, as in the psalm’s “destruction that wastes at noonday.” Around 500 AD, one tractate in the Babylonian Talmud, Pesachim, notes:

There are two types of ketev demons, one that comes before noon in the morning and the other one comes in the afternoon. . . . The ketev in the afternoon is called ketev yashud tzaharayim [the destruction that wastes at noonday] . . . , and it appears inside the horn of a goat and revolves around inside it like a sifter.

A midrash on the Book of Lamentations harks back to 91 when it describes this qeteb as “full of eyes, scales, and hair . . . whoever looks at it falls down dead.”

The Midrash Tehillim expounds at length the various demons believed to be mentioned in 91. On the destruction that wastes at noonday, Rabbi Judah noted only that this was a demon active at that time of day. Rabbi Khunna was more creative in describing the demon Bitter Destruction as

covered with scale upon scale and with shaggy hair and he glares with his one eye and that eye is in the middle of his heart. . . . He rolls like a ball and from the seventeenth day in Tammuz to the ninth day in Av he has power after the fourth hour in the day and up to the ninth hour. And every man who sees him falls upon his face.

Is it just me, or do you agree that the rabbi was thoroughly enjoying himself in offering such descriptions?

Commentators debated what kind of evils the psalm was enumerating, and whether they involved literal demons or more metaphorical evils and sins.

Inevitably, 91 also inspired discussion of angels and their roles, and especially the appealing promise of a protective angel. The Midrash Tanchuma (seventh century AD?) explained the psalm’s v. 11 thus:

When a man performs one precept, one angel is assigned to guard him; when he performs two precepts, two angels are given to him; when he performs all the precepts, many angels are assigned to him, as it is said: For He will give His angels charge over thee. Who are these angels? They are the beings who will protect him from demons, as it is said: A thousand may fall at thy side, and ten thousand at thy right hand. . . . What is meant by may fall? It means that they force [their opponents] to surrender to him.

But those protective angels wielded a two-edged spiritual sword, threatening the ordinary believer who fell into sin. If one who sinned in secret hoped to escape the day of judgment, he would be disappointed. “The two ministering angels who accompany a person will testify against him, as it is stated: ‘For He will give His angels charge over you, to keep you in all your ways’.”

Against the Darkness

Most readers may have cherished the psalm’s protective qualities, but thoughtful commentators were troubled by the use of scripture as a form of magic or incantation. Talmudic sages respected the psalm’s power and used it freely themselves for protective purposes, especially for night prayer. Most agreed that it should be prayed on a daily basis. Even so, they warned that while defensive or “apotropaic” (warding off or turning away) uses were acceptable, there were strict limits. To pray for healing and protection was highly desirable. It was a very different matter to assert that repeating the words or letters of a particular text would somehow compel God or his angels to supply such protection.

Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi, whom I have already mentioned, indicates the fine line to be walked in such practices. He declared that “one is prohibited from healing himself with words of Torah,” which seems explicit enough, yet at the same time, we know that he used protective verses from Psalms 3 and 91: “[He] would recite these verses to protect him from evil spirits during the night and fall asleep while saying them.” That led to one of the exchanges that we often find throughout these texts, where one rabbi has to reconcile the seemingly contradictory opinions of an esteemed contemporary, or predecessor. When challenged to explain the apparent discrepancy, Rabbi Yehoshua replied that “to protect oneself is different, as he recited these verses only to protect himself from evil spirits, and not to heal himself.” Apotropaic uses were acceptable, but curative ones were not. Other rabbis were not as forgiving, and forbade any use of scripture either in healing or for protection.

Through Christian Eyes

Obviously, all these texts must be read totally in their Jewish context, but they can also provide valuable material for Christian scholarship.

Those centuries between roughly 200 and 800 AD cover large portions of the Early Christian Church and the Patristic Era, as well as late Antiquity. Throughout, Jews and Christians were often in close proximity and interaction, and they shared a very large number of assumptions and commonplaces. Still, at the end of the fourth century, a Christian leader like John Chrysostom was hectoring his Antioch congregations to urge them not to join in Jewish feasts and fasts, or to attend synagogues. (His homilies on these relationships still make for eye-opening reading). Jewish-Christian borders were still more porous in regions further east, where the Church of the East would prevail for long centuries. That church spoke Syriac, which was easily comprehensible to Jews who spoke Babylonian Aramaic. For interactions between the two faiths, see the books by Michal Bar-Asher Siegal in the list of references below. On spiritual matters, the kind of demonic material I explore here is very close indeed to what we find in Western Christian contemporaries, such as Cassiodorus.

I would argue that if we just look at such Christian materials, without the Jewish parallels, we are missing a large part of the Early Christian story. That issue runs far beyond notions of demons and spiritual warfare.

The available literature on these topics is of course enormous, but I will just list a few items I find especially valuable.

As an introduction, you can still do far worse than Adin Steinsaltz, The Essential Talmud (Basic Books, 1976, and many later editions).

A really useful academic starting point is Charlotte Elisheva Fonrobert and Martin S. Jaffee, eds., The Cambridge Companion to the Talmud and Rabbinic Literature (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Martin Goodman and Philip Alexander, eds., Rabbinic Texts and the History of Late-Roman Palestine (Oxford University Press/British Academy, 2011)

Richard Kalmin, Migrating Tales: The Talmud’s Narratives and Their Historical Context (University of California Press, 2014),

Hayim Lapin, Rabbis as Romans: The Rabbinic Movement in Palestine, 100-400 CE (Oxford University Press, 2012).

Shai Secunda, The Iranian Talmud: Reading the Bavli in Its Sasanian Context (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013)

Michal Bar-Asher Siegal, Early Christian Monastic Literature and the Babylonian Talmud (Cambridge University Press, 2013)

Michal Bar-Asher Siegal, Jewish-Christian Dialogues On Scripture In Late Antiquity: Heretic Narratives Of The Babylonian Talmud (Cambridge University Press, 2019)

Moulie Vidas, Tradition and the Formation of the Talmud (Princeton University Press, 2014).

See also the (bit dated) bibliography here. From that same BBC site, you can also access on informative podcast on the topic.

Finally, the early twentieth century Jewish Encyclopedia is fully available online. It is of course very dated, but the general level of scholarship is stunning, and the work endlessly repays reading.