My recent work has concerned the Byzantine world in its last days, and that exploration of Midnight in Byzantium, has introduced me to some wonderful stories and fascinating individuals: just how this will end up in published form remains to be determined. But here, I focus on one person who was amazing even by the standards of his age, and who has attracted a sizable scholarly literature – although I have occasionally been startled to meet scholars of Early Modern European history and culture who have never heard of him. If you have ever heard of Erasmus or Thomas More, then you should be aware of George Gemistos, known as Plethon (c.1360-1452). He really did go where no (or very few) thinkers had gone before, or at least had not done for several centuries. His story raises some fascinating questions about tracing the history of very radical religious thought in medieval and Early Modern Christian societies. Can we actually write a history of these deep religious undergrounds?

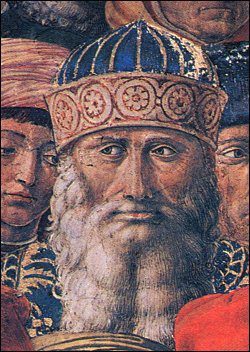

Plethon was a brilliant Neoplatonic philosopher, who flourished in the very rich intellectual life of the later Byzantine Empire, a time that was otherwise marked by so many political disasters and defeats. In fact, the empire’s last couple of centuries are marked by a Palaeologan Renaissance, from the name of the ruling dynasty at the time.

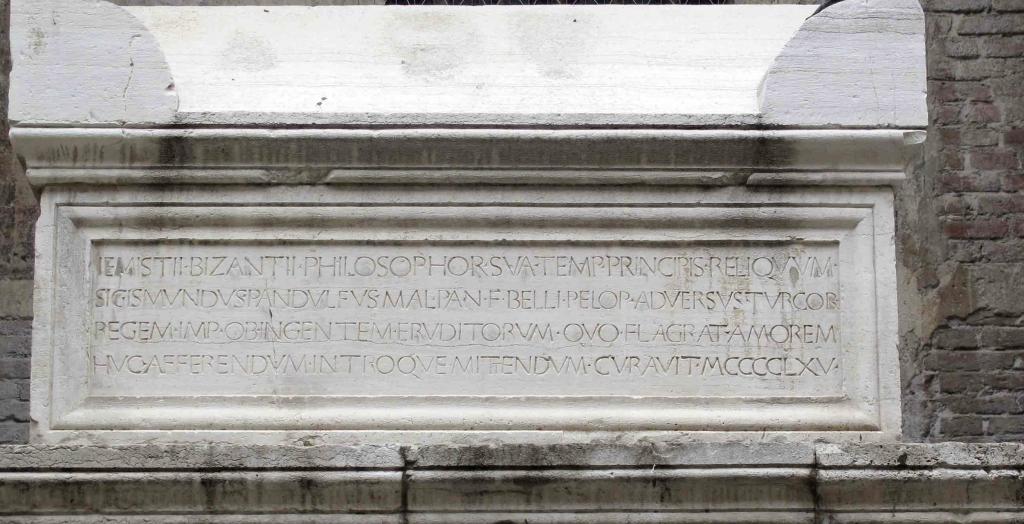

Around 1410, the emperor exiled him from Constantinople to Mystras, in the Peloponnese, in what is now the far south of Greece. Plethon made Mystras a vital intellectual center, at which he trained a generation of key scholars, many of whom would go on to transmit Greek culture and thought to Latin Europe (I described this process in my last posting). When the leaders of the Byzantine church traveled to Florence for the Church Council that would unite Eastern and Western traditions, Plethon’s pupils were very well represented, notably the later Cardinal Bessarion and Mark of Ephesus. Plethon himself spent time in Florence, where he and his teaching created a sensation, spurring a dramatic new interest in all things Hellenic. He was a mighty influence on the burgeoning Italian Renaissance, especially on thinkers like Marsilio Ficino, and did much to introduce the writings of Plato to the Latin world. Edward Gibbon notes how “After a long oblivion, Plato was revived in Italy by a venerable Greek, who taught in the house of Cosmo of Medicis.” Gibbon sharply contrasts the valuable lessons that could be learned from such study with the (what he regards as) sterile Christian nonsense that was so hotly debated at the Council of Florence. Although Plethon died in Mystras, his disciples removed his remains to Rimini, in Italy.

Among other activities, Plethon formulated a scheme for an ideal new Greek nation-state, which has led to him being called the founder of modern Greek identity. His vision has been described as utopian, which is an even more appropriate term than we might assume, as his ideal society probably influenced More’s Utopia (1516).

All these achievements were remarkable enough, but most striking was his rejection of essentially all the religious assumptions of his age. The important thinker George of Trebizond records a conversation at Florence:

I myself heard him at Florence … asserting that in a few more years the whole world would accept one and the same religion with one mind, one intelligence, one teaching. And when I asked him “Christ’s or Muhammad’s?,” he said, “Neither; but it will not differ much from paganism.” I was so shocked by these words that I hated him ever after and feared him like a poisonous viper, and I could no longer bear to see or hear him. I heard, too, from a number of Greeks who escaped here from the Peloponnese that he openly said before he died … that not many years after his death Muhammad and Christ would collapse and the true truth would shine through every region of the globe.

When he died around the time of the Fall of Constantinople – we cannot be sure whether he died occurred before or after that calamity – he left a manuscript called the Nomoi, Laws, which was so daring in its views that the Patriarch of Constantinople commanded that it be burned. Even so, enough survives to suggest the (literally) incendiary contents. Plethon drew on Stoic, Platonist, and Zoroastrian ideas as well as Hellenic paganism, and various occult and esoteric elements. He accepted a divine pantheon, which presided over the eternal transmigrations of human souls, and which directed every aspect of existence. He taught that

These are the principal doctrines that ought to be acknowledged by one who will be prudent.

The first of these is one about the gods: that they are….

Concerning the universe, first that this universe is eternal. Both the second ranking and the third ranking gods are in it. This universe was begotten by Zeus; it was neither begun in time nor will it come to an end. Next that from the many universes it was joined into a unity. Next that the best out of those possible has been made, precisely because it was made by the particularly best being. Once it had been made, it was such that nothing had been left out and anything added to it would be excessive. …

Concerning we ourselves, first that our soul, being of like kind to the gods, is immortal and remains in this universe the whole time and is eternal. Next that the soul is sent down for the purpose of partaking in a mortal body here each time by the gods, at one time in one body, at another in another, on account of the harmony of the universe. That, even though we have a share in mortal things, one thing in us is from the immortals and this is our form.

(Translated by Darien C DeBolt).

Plethon wrote about Olympian gods with such archaic names as Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, and Helios, and also enumerated Tartareans and Titans. He proposed a new state religion for the Byzantine empire, dedicated to the worship of the Hellenic deities.

This whole story raises critical questions of evidence that run far beyond the specific case in question, or indeed of the Renaissance era. Historians are well used to religious controversies where one side denounces the other as having abandoned the faith, of making arguments that are anti-Christian, or even pagan. That is the standard fare in such debates. For the sake of argument, assume that the Protestant Reformation had failed, and that the Reformers’ own writings had largely been consigned to the fire. We would probably remember Martin Luther through the worst lies devised by his enemies, as some kind of Satanic sorcerer who tried to destroy Christianity, and at least some later writers would presumably argue that there was no smoke without fire. Wise historians know to treat such claims with an industrial-scale dose of salt.

Assume for the sake of argument that in Plethon’s case, we did not have all the materials that were undoubtedly from his own pen. If we read a polemic in which some foe accused him of seeking to restore the pagan gods, we would immediately dismiss that as empty rhetoric, or blatant propaganda. Yet that was neither more nor less than he really was trying to accomplish. In this particular case, then, such caution is not called for. His writings are explicit. Arguably the greatest European scholar of his day, who was sought out by emperors for his counsel, was a pagan, who thought that Christianity was in its dying days.

We can make what we like of this, but the Rimini church in which Plethon was buried was the family shrine of the warlord Sigismondo Malatesta, and it was famous for its abundance of pagan and neo-Platonic imagery. Sigismondo himself was regularly denounced for his alleged contempt for Christianity, and we all know how skeptically we should treat such claims …. but thinking back to Plethon’s example, maybe we sometimes protest too much? Maybe outright pagans were not as rare as we assume.

When we look at pre-modern societies, we tend to assume that people largely accepted the conventional religious orthodoxies of the time, and we may think that they were too weak-minded or ill-informed to think differently. It is always interesting to come across those people who genuinely did hold radically deviant or speculative ideas, and such expressions are not hard to find. Early Modern Europeans not only knew very well about people who carefully concealed their authentically subversive opinions behind a normal-looking facade, they had a specific name for them, namely Nicodemites, and I have posted about them in the past.

The problem is how to assess seemingly radical statements or claims. Sometimes, you will find such alternative beliefs expressed in the records of inquisitions or church courts, although you are never too sure when torture is being used to force people to confess to strange notions. Or, we hear of daring and heretical opinions expressed at second hand. Think for instance of the explosive sentiments attributed to Christopher Marlowe around 1590, ”that St. John the Evangelist was bedfellow to Christ and leaned always in his bosom; that he used him as the sinners of Sodoma.” Did Marlowe really say such things, or was an enemy framing him in order to destroy him? Very rarely indeed do we find deviant opinions that we can credibly, indeed certainly, attribute to a particular person (See for instance my attempt to reconstruct the heretical beliefs of a man called Nazarius, a couple of centuries before Plethon’s time).

Plethon, as I have suggested, was a true radical. The question must arise: how many of his friends and pupils shared his views, but were far too cautious to write them down? How many of those who heard him regarded him not as a “poisonous viper” to be feared, but as the prophet of a new dispensation? How would we ever know for sure?

Also on Byzantine matters, I am happy to announce my forthcoming book A Storm of Images: Iconoclasm and Religious Reformation in the Byzantine World (Baylor University Press). Now available for pre-order!