May is my favorite month of the year, not only because it’s Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, but also because it’s a month we celebrate fresh beginnings, from new leaves brightening the branches of trees to new graduates celebrating their accomplishments and starting a new chapter in their lives.

This particular May marks a milestone for me: one decade since I was one of those graduates, a newly minted PhD who delighted in being able to call herself “Doctor” for the first time and who proudly paraded around Manhattan in a black velvet tam and a baby blue gown that had such splendid puffed sleeves that Anne of Green Gables would have surely been impressed.

A few weeks ago, I donned my doctoral regalia once again, this time to stand onstage and give the keynote address at the University of Michigan’s Asian & Pacific Islander Graduation Celebration. The students had chosen the graduation theme of “Up next—you get to decide,” and I had much to say about the “you get to decide” part because, honestly, I can think of few things more overwhelming. Deciding the direction of your life is incredibly daunting. More than anything, I spend my office hours talking with students about choices, not only about the topics for their research papers, but about their future careers and educational plans. Should I take this job after graduation? my students might ask me, and this question is usually a starting point for a longer discussion about more fundamental matters: What are my values? What is most important to me? And what do I want to do with my life? Around every past graduation in my life, from high school through graduate school, I remember asking the very same questions and finding my excitement about the future intertwined with just as much uncertainty about whether I was making the right choices or, instead, very grave mistakes.

Aware that there are probably many new graduates grappling with questions about life choices and inspired by Nadya Williams’ recent essay about “discerning vocation,” I’m sharing my graduation keynote address, which I’ve revised lightly for this blog post. My hope is that it can offer wisdom, encouragement, and reminders to be self-compassionate to those who are facing new beginnings and big choices this graduation season.

On Choosing Well

“Up next – you get to decide”: this is the theme of our celebration, and the musical playlist is the metaphor we are dwelling on today. It’s a very appropriate one, I think. Our entire lives are a lot like a playlist, a collection of songs we curate ourselves that reflects who we are and what we hope for, struggle against, dream of, and love. In many ways, a graduation is like the moment in the playlist of our lives when we shift from one song to another. There’s a lot of anticipation as we wonder: What will we dance to next?

And so I’m going to use this occasion to tell you about my first playlist, which I made when I was ten years old. I’m a historian by training, so I’m going to give you some history here. Unlike many of you graduating today, I was born in a long-ago era commonly known as “the late 1900s,” and in this far-off time, we didn’t have Spotify or streaming services, but mixtapes—physical, plastic cassette tapes. And to make my first mix tape, I loaded a blank cassette tape into my state-of-the-art tape player and recorded songs off the radio.

It was 1992. My favorite song was “End of Road” by Boyz II Men.

I loved that song so much that I recorded it ten times on one mixtape. This project took real dedication: an entire weekend of sitting by that tape player and waiting patiently for the song to come on the radio and then pouncing to press ‘record’ when it did.

The tape was an unusual mixtape because, well, there was no mix. It was literally a playlist with the same song, recorded ten times. My friends thought my mixtape was boring and obsessive. I thought my mix tape was glorious. It was exactly what I wanted. It was mine, something that reflected what I loved, a creation of my choice.

In the playlist that is our life, we need to make choices. It’s a responsibility we face all day, everyday. Not only do we need to make choices, but we need to make good ones. We’re constantly reminded—by our family and friends, by the news and social media, by our own conscience—that we must choose wisely because our individual and collective futures depend on it. In order to be healthy, we need to choose the right food to eat, the right type of exercise, the right amount of sleep. In order to be successful, we need to choose the right major, the right classes, the right internship. In order to be happy, we need to choose the right career, the right romantic partner, the right place to live.

The fact that we are faced with so many choices that shape the course of our lives is exhilarating and empowering. It’s also exhausting. Decision fatigue is a real thing! There’s a reason why Barack Obama had a closet full of suits that were all basically the same—the presidential wardrobe version of my Boyz II Men mixtape. As he explained, “You’ll see I wear only gray or blue suits. I’m trying to pare down decisions. I don’t want to make decisions about what I’m eating or wearing. Because I have too many other decisions to make.” And anyway, remember that time he tried wearing tan? It didn’t go so well. Sticking with navy: good choice.

Another reason why making choices is overwhelming is that it’s hard. To be sure, some choices are pretty easy. For example, suppose somebody is choosing between attending two colleges, the University of Michigan or Ohio State University. There’s clearly one right answer here.

But more often than not, we’re faced with decisions that don’t have an obvious right answer. Making choices is hard when there are a lot of unknowns, when there’s no clear best choice, when you have a lot of good options, when the consequences of your actions are overwhelmingly big, when you’ve never had to make such a big decision before.

Students in their final year of college often face all these challenges, and graduating seniors sometimes find their way to my office, seeking advice about what they should do next. Should they apply to graduate school? Move to Chicago? Travel abroad? Stay here and save up some money doing a familiar job closer to home?

Now, I’m a religion scholar, so I’m going to make a confession here: The truth is that, at forty years old, I’m often asking the same questions. Is this what I should be doing? Is this where I should be? These are the things I wonder.

But despite the fact that I’m continuing to figure things out, I do have some experience making choices, some of which have been good and wise, and others, less so. Throughout this process, I’ve learned a lot about the art of choosing.

So, while I acknowledge it’s a bit audacious because I’ve made my own fair share of mistakes, I’d like to share three rules for making good choices in life.

Rule number one: Approach every hard choice as an opportunity in itself.

Specifically, every hard choice is an opportunity to grow: to be in conversation with yourself and others and to learn about and reflect on your priorities, your values, and your needs, as well as those of the people you love. It’s a chance to know who you are and thus to create who you are.

In this regard, the chance to choose is a great gift. You don’t have to make a choice—you get to make a choice, and you get to be a wiser, more self-aware, and more intentional person because of the thinking and reflection involved with making that decision.

Sheena Iyengar, a social psychologist who researches choice, puts it this way in her book The Art of Choosing: “The chiseling, the carving out through our decisions, is what defines who we are. We are sculptors, finding ourselves in the evolution of choosing, not merely in the results of choice.” In Iyengar’s view, choosing is a “liberating act of creation.” She notes, “The writer Flannery O’Connor reportedly said, ‘I write to discover what I know.’ Perhaps we can take a page from her book and say, ‘I choose to discover who I am.’”

Rule number two: Always say YES.

This advice might be surprising, so let me explain. I’m not saying that you shouldn’t ever utter the word “no.” For example, I think that the advice from the late 1900s R&B group TLC is pretty sound: “no scrubs”—unless, of course, you’re a surgeon.

But what I am proposing is that when you say “no,” you reframe it as a moment when you are actually choosing to say “yes” to something that is deeply important to you. What I’m recommending is that you always strive to say what Lysa Terkeurst calls your “best yes,” which are the actions that reflect your most fundamental values and are in keeping with what you see as your personal mission.

Often a “best yes: and a lifetime defined by courageous, purposeful action emerges from a “no.” Here, I point to the lives of two fierce Asian American feminist activists whom I greatly admire, Grace Lee Boggs and Helen Zia.

For Grace Lee Boggs, the world said no, and that opened up the opportunity for her to say her best yes to something truer to herself. Born in 1915, Boggs graduated from Barnard College and earned a Ph.D. in philosophy from Bryn Mawr College. But there were few opportunities for academic careers available to women at the time. So she moved to Chicago and became involved in labor activism and Black civil rights organizing there, especially around fair hiring practices. She later recalled, “When I saw what a movement could do, I said, ‘Boy, that’s what I wanna do with my life.’” From there, she said her best yes to a decades-long career committed to a number of social causes: Black power, women’s rights, environmental justice, anti-war activism, Asian American organizing, and more.

Helen Zia, on the other hand, chose to say no, and that opened up the opportunity for her to say her best yes to an activist life that felt more authentic. Helen Zia studied at Princeton in the 1970s as a member of its first graduating class of women. As a student, she helped found the Asian American Students Association and was involved in anti-war and feminist movements on campus. But after graduating, she wasn’t sure what to do with herself, and so she pursued the default option: medical school. It was not the right fit for her. After two years, she said no to medical school, thus “spurning her path to respectability, wealth, and filial nirvana,” as she put it. Instead, she moved to Detroit, worked in an auto factory, became involved in labor organizing, and discovered journalism. When Vincent Chin was murdered in 1982 amid a rise in anti-Asian sentiment, Helen Zia was one of the leaders in the movement to call for justice for his killing. Today she is one of the nation’s most prominent Asian American leaders, and all this is possible in part because she said no to medical school and said her best yes to a career in activism that felt closer to her values and her mission.

Rule number three: Remember that your happiness depends not only on making the right choice, but on making that choice right.

After investing time and effort into making a good decision, you might think that your work is over and that your happiness is settled. But that’s not true! Making sure our decisions work out for the best requires continuous attention, effort, and care.

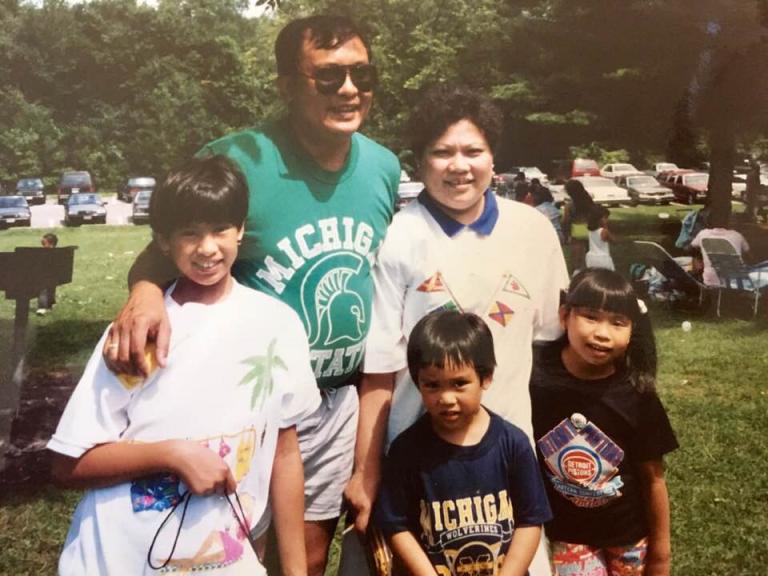

On this point, I think about the example of my parents, Frank and Eleanor, who, perhaps like many of you in the audience, are immigrants. They came to the United States from the Philippines in the early 1980s with big hopes and dreams for themselves and their children.

And where did they choose to pursue these hopes and dreams? Saginaw, Michigan. I love Saginaw. Some people call my hometown “Sagnasty.” I fondly call it “Saginawesome.”

I loved growing up in Saginaw, but let me be clear: Filipino family members thought my parents had made a strange choice. Everybody wondered why they had traded the tropics for the tundra. (The mangos are terrible in Saginaw!) And my Uncle Oscar, who lived in California, kept trying to convince my parents to move to L.A. so their daughter—me—could “become a star.”

Well, I never became a star because my parents felt good about Saginaw and stayed. They liked its down-to-earth atmosphere, friendly people, and affordable cost of living. To a young couple looking to establish themselves in America in 1982, Saginaw seemed like the best place for their young family to call home.

What they felt in 1982 turned out to be true: it was a great home, though not because there’s anything inherently special about Saginaw. It was a great home because over the past four decades, my parents made it a great home. They cultivated wonderful friendships and invested in the community. My dad served on the school board, and for years, my mom cheered for the high school football team, well past the time she actually had kids at the high school. In other words, Saginaw ended up being the right choice because my parents insistently and actively made it the right choice. And they were very happy as a result.

Well, friends, it’s your graduation, and to quote from the ever-insightful Boyz II Men: “we’ve come to the end of the road.” At this part of the journey, maybe, like Boyz II Men said, you can’t let go. Or maybe you’re really eager to move on. Or maybe you felt like I did on graduation day: excited but uncertain, because the world is big and beautiful, and you don’t want to waste a single second of the glorious gift that is your life. This is all okay.

My hope for you as you look to the future is this: that you take the time to embrace the opportunity to make wise choices that are the best for you. That you find a way to say your best yes. That you find a way to make the right choice, and to make that choice right. And that you find yourself in the process.