This post concerns a painting I first encountered many years ago, and which has remained something of a guilty pleasure. It’s not necessarily a great work of art, but it is very revealing for the religious and cultural thought of the world from which it comes, namely the mid-nineteenth century. It says a great deal about how Protestants and Catholics defined and demonized each other in that era, and long afterward, and how religion spilled over into understanding global affairs. It also illustrates how we have to unpack some art works to understand their full meanings. To put it crudely, there is a lot more going on here than immediately appears.

Understanding a Painting

The painting in question is “Burying the Bible” (1861), by Joseph Severn (1793-1879) and it is located in the Russell-Cotes Gallery in Bournemouth, England.

At first glance, it tells a simple and dramatic story. It is Naples in 1540, and a Protestant couple are burying their greatest treasure, a vernacular Bible. They are doing this because of fear of Catholic authorities, and the Inquisition. In the background, we see a Catholic religious procession, with images of saints or the Virgin. The man is trying to seize one last glance at the precious Bible, while his wife is urging him to hurry: if they are found in possession of this sacred contraband, then their lives are forfeit.

On closer examination (which is not possible in the image I reproduce here) you discover some deeper dimensions. The Bible text that the man is reading is Leviticus 26:

Ye shall make you no idols nor graven image, neither rear you up a standing image, neither shall ye set up any image of stone in your land, to bow down unto it: for I am the Lord your God.

The large thistle bush recalls Matt 7. 15-16:

Beware of false prophets, which come to you in sheep’s clothing, but inwardly they are ravening wolves. Ye shall know them by their fruits. Do men gather grapes of thorns, or figs of thistles?

Putting these elements together, we get a very grim picture of Catholicism, combining the two main aspects of contemporary anti-Catholic and anti-clerical rhetoric in England and the USA alike. Catholicism is dominated by clergy who are vicious deceivers of the people, who use any violence or fraud to conceal the Christian truth from their gullible flocks. At every stage, Catholic practice violates the basic Old Testament prohibitions of idolatry, and elevates lesser figures like the Virgin Mary to something like divine status. Both the Bible verses alluded to were mainstays of anti-Catholic polemic in this era, and especially the Leviticus one.

As I have often stressed, so much of the appeal of Protestantism throughout its history has been based on these principles, rather than any detailed intellectual appreciation of the theologies of Martin Luther or John Calvin. Historically, iconoclasm was as much a part of traditional Protestant appeal as justification by faith. (Discuss!) In a larger sense (according to this vision) Catholic power relied wholly on repression, persecution, and armed force.

Anti-Catholicism

If you want to know what ordinary Anglo-American Protestants thought about Catholics and Catholicism in the mid-nineteenth century, you could do a lot worse than examining “Burying the Bible.” To take one example, this was why American Protestants were so nervous of allowing rival Catholic Bible translations in schools: without the Bible in its pure Protestant form, Christianity would be subverted, and ultimately destroyed. You might just as well bury the true Bible in the ground.

But if the views expressed are what we might call generically Protestant, is there any specific reason why they should appear in a painting at this date? Why 1861? And why the Naples setting? Like other major Italian cities, Naples did indeed have an authentic history of indigenous Protestantism in the sixteenth century (which was duly eradicated), but it was no more noteworthy than many other Italian centers. But as I will show, the city had a special political and religious resonance precisely in and around 1860: it was very much in the news.

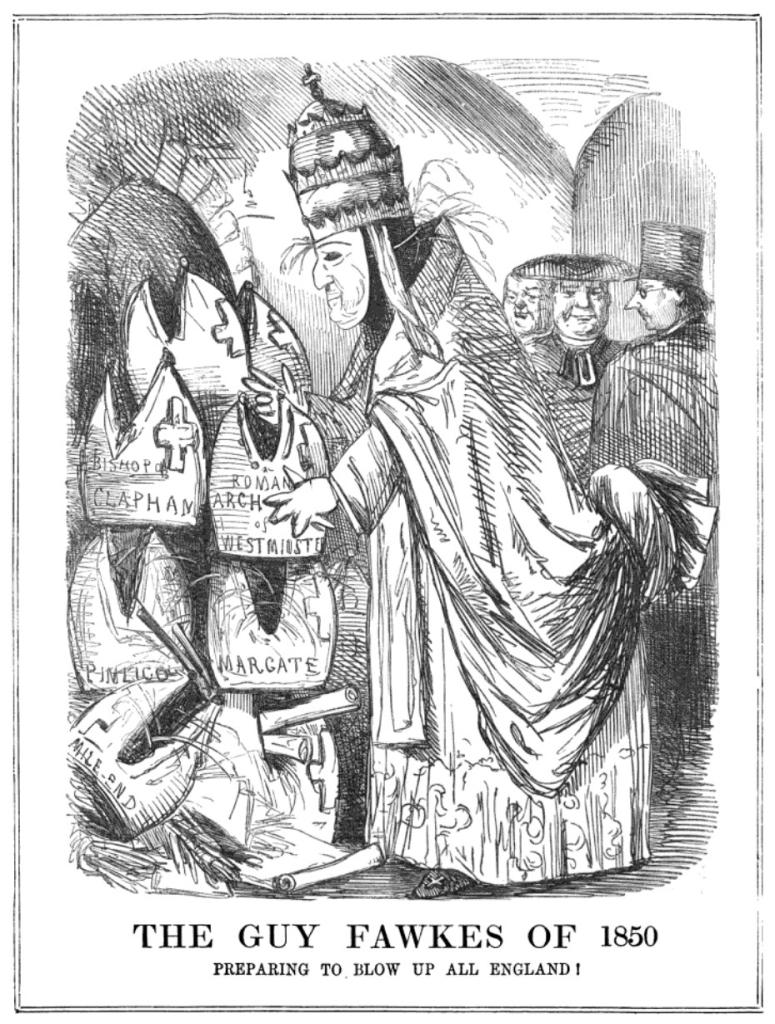

Two distinct but related stories are in play here. In the English context, we have to think of the “high church” movement in Anglicanism, the Oxford Movement, which emerged in the 1830s. In a series of controversial Tracts, the movement advocated the restoration of many practices and devotions that were traditionally regarded as Catholic, leading critics to denounce its followers as crypto-Catholics. Such charges became ever more plausible with the publication in 1841 of Tract 90, which advanced quite extreme positions. In 1845, the leading Tractarian John Henry Newman sensationally converted to Catholicism, fulfilling all the worst fears of subversion, and other conversions followed. In the same years, mass Irish migration to Britain and the USA created very large Catholic populations. Anti-Catholicism ran rampant.

But more precisely, there was also an Italian dimension. This was the era of the movement for national unification, the Risorgimento, the Rising Up Again, or Resurgence. The movement was led by heroic figures such as Giuseppe Garibaldi, who became a global revolutionary superstar. On the other side, the forces of reaction had two notorious capitals, respectively in Rome and Naples. In Rome, Pope Pius IX was the deadliest foe of Italian nationalism, and of any and all progressive or vaguely modern causes worldwide. Naples, meanwhile, was the capital of the absolutist Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, under the Bourbon dynasty. Although there were many candidates for the title, perhaps the most notoriously reactionary sovereign of the day was King Ferdinand II of the Two Sicilies, (1830-1859), who in 1848 had mercilessly bombarded his subjects during a liberal insurrection at Messina. Ever afterwards, he was known as Re Bomba, King Bomb. “Bomba” himself died in 1859, but he was succeeded by his highly conservative successor, Francis.

That context explains why the events of 1860 were so transformational. In a spectacular victory, Garibaldi captured Naples, and then pressed on against the forces of the Papacy. In 1861, the Sardinian monarch Victor Emmanuel II was proclaimed King of Italy, a state which claimed Rome as its capital, although that city was not formally captured until 1870. These events created something like a messianic mood not just in Italy, but among liberals and progressives across Europe, who were overjoyed to see the overthrow of Papal power, and of absolutist tyranny.

Naples, I should explain, had a special place in anti-Catholic rhetoric, because of the annual miracle in which the blood of the city’s patron saint and martyr, Januarius, liquefied in a public spectacle. Protestants, obviously, believed this was outrageous trickery of the sleaziest kind, and they ruthlessly mocked anyone who took it seriously. Believing in saints and healing miracles was one thing, but miracles on demand were several bridges too far. This was Catholic superstition on steroids. Ideally, Garibaldi’s liberation of the city should mark the end of such nonsense. That theme is perfectly illustrated in the Punch cartoon here of Garibaldi kicking Januarius out of Naples in 1860: the revolutionary Hero confronts the trickster Saint. Do check it out (I am not sure about copyright rules for reproduction, so I will err on the side of caution). The same applies to a couple of other British cartoons on Italian affairs from the same year on related themes, on the evils of Popery and tyranny.

These Italian events had a profound impact on the Anglo-American cultural figures who so loved the country, most famously the Brownings, who did so much to shape British views of Italy, past and present. Others included Nathaniel Hawthorne, Margaret Fuller, Arthur Hugh Clough, and related topics appear in the writings of other key figures of the 1850s and early 1860s, such as Charles Dickens. The Italian struggles of these years had a worldwide influence comparable to that of the Spanish Civil War of the 1930s.

Joseph Severn

To get back to our painting. This was the work of Joseph Severn, who was famous as one of the dearest friends and supporters of legendary poet John Keats, and who cared lovingly for Keats in his final days. Severn was very well connected in English literary and artistic circles. In that critical and very sensitive year of 1861, he also received the post of British Consul to Rome, where his superiors desperately wanted him to avoid major controversy or embarrassment. Severn repeatedly violated his orders, supporting liberal and nationalist activism, and he was repeatedly rebuked by the British government.

It was at this point that he created “Burying the Bible,” which in the context of the time has to be regarded as a very provocative anti-Catholic and specifically anti-Papal polemic. Although it could have been set notionally anywhere in Italy, the precise named setting is Naples, as Truth was being laid in the ground, ready to be excavated and restored in some distant future age – a time of Risorgimento, or even of Resurrection. For anyone seeing the painting at the time, “Naples” would immediately summon images of Garibaldi’s victory the previous year, and the triumph of the anti-Papal Italian cause. Of course, Severn was under no illusions that Garibaldi and the national leaders were Protestants, but in the world view of British liberalism at the time, the causes of liberty, democracy, and the Gospel were indissolubly intertwined, just as thoroughly as Catholicism was inextricably bound up with autocracy and obscurantism.

For Severn, Bible Truth was buried in Naples in 1540, but was restored in that same venue in 1860. That link between religious and civil liberty, with the Bible as central symbol, would resonate wonderfully with Baptists of any era.

And Longfellow Too

Some years ago, I blogged at this site about a poem from this very same time, which has substantial areas of overlap with “Burying the Bible” in theme and approach. This was “The Sicilian’s Tale: King Robert of Sicily,” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, dating from 1863. You can link to my post easily enough, so I won’t say much about it here, except that the poem likewise uses a historical (medieval) setting to celebrate the cause of Garibaldi and the nationalists, and the overthrow of the tyrannical regime in Naples specifically. As I wrote in that earlier post:

As a good liberal New Englander, Longfellow sympathized totally with the rebels, whom he saw as fighting for progress and enlightenment – distant allies in the wider cause that the North was fighting for in the ongoing American Civil War. In 1861, indeed, Garibaldi had modestly volunteered to become commander in chief of US forces in that conflict. The fact that the Italian nationalists were fighting against what was perceived as oppressive Catholic tyranny was an added bonus.

Taken together, poem and painting tell us a great deal about liberal and Protestant ideas in that era, and the historical mythologies that they created to support them.

SOME SOURCES

Gioele de Bartolomeo, “La Bibbia “seppellita”, metafora dell’Italia in un quadro di Joseph Severn” (2021)

Sue Brown, Joseph Severn – A Life: The Rewards Of Friendship (Oxford University Press, 2009)

C.T. McIntire, England Against The Papacy, 1858-1861: Tories, Liberals, And The Overthrow Of Papal Temporal Power During The Italian Risorgimento (Cambridge University Press, 1983)

Danilo Raponi, Religion And Politics In The Risorgimento: Britain And The New Italy, 1861–1875 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014)

Grant F. Scott, ed., Joseph Severn: Letters And Memoirs (Ashgate, 2005)