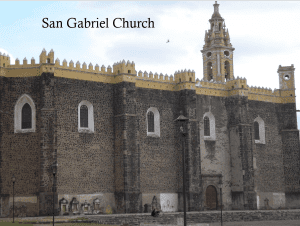

May my body be buried in the Church of San Gabriel in the said

city of Cholula in the tomb that the father guardian or president of

the said convento will indicate to me…. Bury me in the habit of the

blessed one, San Francisco; it is for the said effect that I ask it.

– doña María Tlaltecayoa, 1596

Archivo de Notarías, Puebla (AN-P), Cuaderno 18, No. 1276, folio 8r. Full document: folio 7r-9v

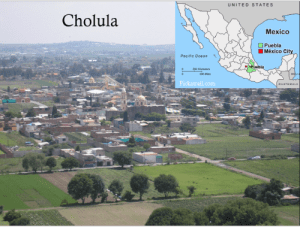

In my February post, “Death, Judgment, Heaven, and Franciscan Habits: The Art of Dying in Late Sixteenth-Century Spanish-Indigenous Cholula,” I opened with these lines from the last will and testament of doña María Tlaltecayoa, an india principal, or a high-ranking native woman whose lineage dated to the pre-contact period. Married to Juan Cardoso, a Castilian labrador, or low-ranking farmer who owned lands and the right to native labor to work it, they lived on the marshy boundaries of Cholula’s jurisdiction, a city in the modern Mexican state of Puebla. Like nearly everyone in the collection of 25 Spanish-language wills I discussed, doña María Tlaltecayoa requested interment in Cholula’s Franciscan church wearing a Franciscan habit, a medieval European tradition prompted by St. Francis himself, who on his death bed removed his habit so that he could die humbly without attachment to material goods. A fellow friar, so the story goes, lent him a habit so that he could enter heaven properly attired (Carlos Eire, From Madrid to Purgatory: The Art and Craft of Dying in Sixteenth-Century Spain, 110). I ended that post with a bit of a teaser, asking if the pious tradition of requesting a friar’s habit meant something different to doña María Tlaltecayoa, being that she was an india principal bridging two traditions. I’d like to explore that question now.

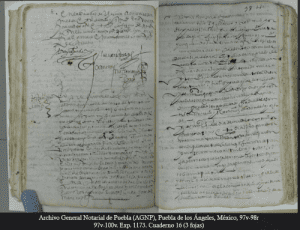

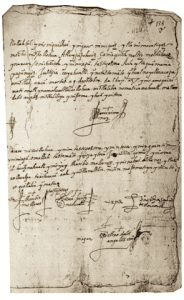

On May 23, 1596, in the city of Cholula, New Spain, Juan Cardoso appeared before the corregidor, or supervising Spanish official, to request that a notary be sent to his home because his wife was ill and desired to dictate her las will and testament. Accompanied by the alguacil mayor, or high constable, and a Nahuatl interpreter, the scribe ventured to the marshy boundaries of Cholula’s jurisdiction to assist doña María Tlaltecayoa, india principal. Despite being the will of a high-ranking native person, the resulting Castilian-language testamento closely adheres to the Early Modern Spanish model, varying little in substance from the Spanish wills of her European contemporaries in Cholula. Where her will does vary is its narrative style, being the only testament in the collection with preliminary material contextualizing its composition, a stylistic technique reminiscent of the Nahuatl, rather than the European, testamentary tradition (I explore the Nahuatl tradition below). Among the wills in the Cholula corpus, doña María is the only testator to self-identify as a native person.

By requesting burial in a Franciscan habit, doña María, like her contemporaries, was conforming to Castilian custom. But she may have also been maintaining continuity with pre-contact Nahua death ritual, a negotiation predicated upon her ability to converse in two cultural and spiritual languages. As a Christian, being vested at death in the discarded robes of a local friar provided her with the “said effect,” that is, she accessed Cholula’s Franciscan economy of grace, taking the holy, seraphic founder of the Order, St. Francis, as spiritual insurance, if you will, against her own personal sin. Within a Christian context, such a death bed request functioned as a symbolic rejection of the world and an aspiration towards personal sanctity. But to a Nahua-Christian like doña María, being wrapped at death in the habit of St. Francis would have resonated with her ancestral practice of shrouding a corpse to protect the soul from angry gods in the underworld. She may have viewed the similarity of the two traditions as an opportunity to imbue her Christian future with her native past, thus preventing a complete eclipse of her indigenous identity within her sixteenth-century Nahua-Christian self.

Let’s examine this further.

Doña María’s Death Bed Narrative

In addition to Juan Cardoso, the notary, the alguacil mayor, and an interpreter, three witnesses stood at doña María’s bedside on May 23, 1596. Now, the presence of an interpreter does not necessarily indicate that doña María did not speak Spanish. It’s not clear from the will whether the notary and alguacil mayor spoke through the translator or merely spoke in his presence. Doña María may have requested or even hired the interpreter to add a layer of protection between herself and the Spanish colonial system, someone who could help her safeguard her interests and those of her community.[1] In the presence of the interpreter and witnesses, the alguacil mayor asked doña María if she wanted her husband to remain present or if they should escort him out of the house to leave her at her liberty, and she made clear that her husband was to remain during her dictation because she had already communicated to him her last wishes.

The notary follows custom by writing the will in the voice of doña María, recording her declaration that she is the legitimate daughter of Diego Tlaltecayoa and Isabel Tlapapaltze, his legitimate wife, both indios principales from the cabecera of Santiago and both native to the city of Cholula, and the legitimate wife of the Castilian Juan Cardoso. Following Spanish formula, doña María acknowledges that though she is ill of body she is sound of will and possesses all of the sense and understanding and natural judgment God gave her.

Like her fellow European Catholic testators in Cholula, doña María opens her will by entrusting her soul to Our Lord God, and requests burial in the Franciscan church of San Gabriel with “the habit of the blessed one, St. Francis (“un hábito del bienaventurado San Francisco;” see AN-P, Cuaderno 18, No. 1276, folio 8r). As I discussed in my previous post, by this point in the 1590s, Cholula was a thriving Franciscan center with over twenty friars in residence, some of whom were trained as Nahuatl preachers.

It’s interesting to note that the Franciscan chronicler, fray Gerónimo de Mendieta, records in his 1596 chronicle the love native peoples had for the habit of St. Francis. According to him, if a friar could not be assigned to an indigenous town the native inhabitants would request that at least they be sent a habit to elevate on a pole on Sundays and holydays and pray that it preach to them (Gerónimo de Mendieta, Historia Eclesiástica Indiana [1596], México, D.F.: Editorial Porrúa, 1993; 330-331). We must be careful, of course, to accept the Franciscan interpretation of indigenous desire for a friar’s habit without considering that the native people may have been motivated by reasons other than Christian piety.

Title page of Book Two of Gerónimo de Mendieta’s History of the Indian Church that treats of the rites and customs of the Indians in New Spain in their infidelity

The section of doña María’s will dealing with spiritual concerns is not at all remarkable. Because of the Spanish notary, her testament contains standard European formulae also present in the other Cholula wills. As a member of the cofradía del Santísimo Sacramento (Confraternity of the Most Blessed Sacrament), for example, she requests that the confraternity oversee her interment. She instructs her executors to give the convento de San Gabriel one hundred pesos in alms to cover the cost of a habit, her funeral procession, her burial, an unspecified number of open casket Masses, and so that the friars, moved by charity, might commend her soul and the souls of her parents to God. She also leaves alms for Masses in Puebla and for the souls in Purgatory. The will goes on to outline her debts and properties.

The preamble to doña María Tlaltecayoa’s will provides some insight into the transatlantic transfer of the intricate Spanish death ritual to colonial Mexico. Much like in Spain, her husband summoned the notary to her bedside during her final illness, indicating, perhaps, a tenderness between them as well as his concern that she produce this important religious document before her death in order to receive the Masses, prayers, and friar’s habit that they believed would ensure the repose of her soul. On a practical level, both doña María and her husband would have wanted to ensure that her property was appropriately distributed after her death, her debts paid, and her bills collected, so as not to inhibit her repose in the afterlife.

Unlike the custom in sixteenth-century Spain, doña María’s cofradía brothers and sisters did not appear at her side during her death throes. Rather, she and her contemporaries in Cholula requested in their wills that their cofrades accompany their corpse in a funeral procession on the day of their death. Nor did friends, the poor, or additional family crowd around doña María’s death bed, not even her brother Francisco, who lived in an adjoining lot in Cholula’s periphery. The prologue does not mention the recitation of prayers for the dying, the reading aloud of devotional literature, or the chanting of pious hymns, as customary in Early Modern Spain. Whether the customs differed in Cholula or these activities would occur after the departure of the colonial officials is unclear from the document.

Last Will and Testament of María de la Paz, 23 October 1595, a contemporary of doña María Tlaltecayoa

Importantly, in colonial Mexico there was no direct connection between the writing of a testament and the priest’s administration of Last Rites (Susan Kellogg and Matthew Restall, Dead Giveaways: Indigenous Testaments of Colonial Mesoamerica and The Andes. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1998; 20). In fact, notaries in New Spain were not obliged to notify a religious authority of a testator’s imminent death, which explains why the preamble to doña María’s will does not mention a priest or reference the sacrament of extreme unction. Neither does the notary mention bell-ringing in any of Cholula’s churches or chapels on May 23, 1596 to mark the imminent passage of one of its faithful, as was customary in Spain. And despite the popularity among native testators in central Mexico of leaving alms for bell-ringing upon one’s death, doña María does not request that bells be rung to signal her passing. Even so, her will reflects the Nahuatl testamentary tradition in other ways.

Nahuatl Testaments

Nahuatl wills first appeared in New Spain in the 1540s and quickly gained popularity among native peoples, deviating more and more from Spanish models as the colonial period advanced. European friars introduced the practice during the first decades of evangelization, since the religious nature of testaments offered an opportunity to concisely transmit Christian concepts while reinforcing the basic tenets of Catholic belief and practice. Although no examples of pre-contact wills survive, it is possible that a Nahua oral tradition existed whereby a dying native person would give final commands to an audience (Rebecca Horn and James Lockhart, “Mundane Documents in Nahuatl,” Sources and Methods for the Study of Postconquest Mesoamerican Ethnohistory, 2010; 2). This may explain why the European testament genre was accepted so readily and became so widely-used among colonial native peoples.

Perhaps because of this pre-contact tradition, colonial Nahuatl wills differ from the Spanish model in several ways. In addition to being considered primarily an oral transaction carried out before an audience of listeners, Nahua testators often spoke directly to those present, unlike Spaniards who would always reference others in the third person even as they dictated their wills in first person (Horn and Lockhart, “Mundane Documents in Nahuatl,” 4). Though doña María follows the Spanish tradition of speaking about those in the room in the third person – namely, about her husband – her desire to dictate her will before an audience of listeners may reflect her desire to adhere to Nahuatl testamentary traditions, despite executing her will in Spanish. Having three male witnesses also follows Spanish custom, though their presence throughout the dictation of the will was not required in Castilian law.

Another related indigenous strategy was to seek out the highest local indigenous authorities to serve as witnesses, thus representing the enforcing power of the community more officially than the other, often numerous, native witnesses could. This might explain the presence of the alguacil mayor at doña María’s deathbed. Despite being a Spanish authority, his witnessing and signing of her will could reflect Nahua custom since, as a fellow labrador, he may have worked with doña María’s husband and lived among the indigenous community on the edge of Cholula’s jurisdiction, possibly quite near to doña María. Perhaps the two families had developed more than a strictly professional relationship and his attentiveness to her final hours reflects that friendship.

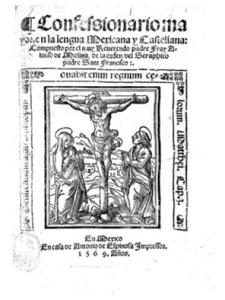

Title page of Alonso de Molina’s 1569 Confession Manual in the Mexican language and Castilian

The only known sixteenth-century model for Nahuatl testaments appeared in a 1569 Nahuatl-Castilian confession manual penned by the Franciscan fray Alonso de Molina. Designed to aid European mendicants in administering sacraments and providing pastoral care to native peoples in central Mexico, the Confesionario mayor en lengua Mexicana y castellana also contained a detailed set of instructions outlining the format and structure for recording Nahuatl wills that a priest was meant to provide to a notary (the full Spanish-Nahuatl text of the Confesionario Mayor is available online at http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/servlet/SirveObras/02585175333505284454480/index.htm). The directions and the model testament underscore the religious nature of will-writing while also providing insight into Spanish attitudes towards native peoples in this period.

According to Molina’s instructions, a good notary was known by his personal qualities and capabilities for performing his responsibilities properly, not by his racial or cultural identity. (Sarah Cline, “Fray Alonso de Molina’s Model Testament and Antecedents to Indigenous Wills in Spanish America,” in Dead Giveaways: Indigenous Testaments of Colonial Mesoamerica and the Andes, ed. Susan Kellogg and Matthew Restall. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1998, 19.) In fact, Molina’s directions asked the notary to carefully consider his personal qualifications since he was obliged to faithfully execute his office. This responsibility included ensuring that the testator remained lucid of mind and judgment, given that testaments dictated by an unsound person held no legal or spiritual force. Among colonial Nahuas, little expectation existed for healthy individuals to produce a will, another departure from the Early Modern Spanish recommendation of producing a will as a pious act while in good health.

Gathering the witnesses was another of the notary’s duties and for this Molina provided strict guidelines regarding the types of individuals who could or could not fulfill this function. For example, neighbors and kin of the dying person were forbidden to serve as witnesses. Instead, six, eight, or ten individuals who lived further away from the testator and who were mature men should fulfill this role. Molina was insistent that those living in the same home as the testator should remain apart from the bedchamber so as not to hear the dying individual’s words. This was to ensure complete freedom for the testator to speak without pressure from prospective heirs (Sarah Cline. “Fray Alonso de Molina’s Model Testament and Antecedents to Indigenous Wills in Spanish America,” Dead Giveaways, edited by Kellogg and Restall, 20). This notarial caution might explain why Cholula’s alguacil mayor asked doña María if she would like him to escort her husband out of the room before she dictated her will. As you will recall, she insisted he remain present, which conforms more to the Nahua tradition than to Molina’s instructions, since native peoples often included their family members and spouses as witnesses. As Sarah Cline has noted, the familial natural of Nahuatl testaments was clearly at variance with the European standard outlined in Molina’s Confesionario (Cline, “Molina’s Model Testament,” 20).

Page from the 1607 Nahuatl testament of doña María Ximénez, Cuernavaca, México

Prior to European arrival, high-ranking native peoples had supervised the functioning of the pre-conquest temple (James Lockhart, The Nahuas After the Conquest, 206), such as the Quetzalcoatl Sanctuary in Cholollan (as it was known). Depending on her age in 1596, doña María may have witnessed the construction of the Franciscan church dedicated to San Gabriel on the site of Quetzalcoatl’s temple, completed in 1552. It is more likely, however, that her parents, who were small children when the friars arrived, participated in its building program. As indios principals, they may also have become involved in overseeing the new church’s operations like their pre-contact counterparts. As their daughter, doña María herself may even have been involved in some capacity with the San Gabriel church.

In what other ways did native traditions prevail?

Nahua Funeral Ritual

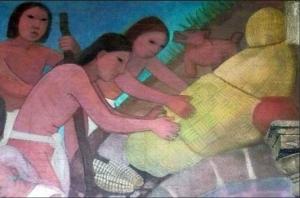

In my previous post, I mentioned a pre-conquest ceremony known as miccaquimiloa or the “shrouding of the corpse,” suggesting that as a Nahua-Christian, doña María Tlaltecayoa may have understood Christian death ritual in this context (León García Garagarza, “The Year the People Turned into Cattle: the End of the World in New Spain, 1558,” Centering Animals in Latin American History, edited Martha Few and Zeb Tortorici, 2013; 31-61). During this rite, the deceased’s body was carefully dressed in various layers of ritual vestments meant to serve as protection during each stage of the soul’s harrowing journey in Mictlan, the Nahua underworld. Importantly, the Nahuas had no binary between good and evil, and thus no equivalent concept for heaven and hell, since in their world view, all things – people, animals, plants, and gods – possessed both good and evil characteristics (Louise Burkhart, “The Solar Christ in Nahuatl Doctrinal Texts of Early Colonial Mexico” Ethnohistory 35, no. 3 (1988): 238).

During the miccaquimiloa ceremony, the body would first be wrapped in a tequimillolli, or a cloth shroud, meant to protect the soul from the itzehecameh or bitter flint-winds in Mictlan, as described by fray Gerónimo de Mendieta. Next, Nahua specialists known as amatlamatque would dress the body in paper vestments specially fashioned with symbols directed at the deities to whom the corpse was dedicated, and useful, as well, to appease other, dangerous gods in Mictlan. During this process, the amatlamatque, or the paper-cutters, would give speeches, instructing the soul about the use of each of the paper pieces they were placing upon him or her (García Garagarza, “The Year the People Turned into Cattle”).

These paper vestments had particular functions distinct from the protection offered by the cloth shroud, namely, they were meant to ward off treacherous gods in Mictlan so that the soul would not be devoured or transformed into an animal. Before the last part of the rite, which was cremation, the native priests would wash the corpse’s head, provide the body with drinking water for its journey in Mictlan, and then place a piece of jade – or a less valuable stone if the individual was poor – into the mouth of the deceased. The Franciscan chronicler fray Toribio de Benavente Motolinia mentions this custom in Memoriales (García Garagarza, “The Year the People Turned into Cattle”). This act was meant to ensure that the person’s heart-soul (yolotl) continued in the afterlife. The entire funeral bundle – bound in a shroud and then wrapped in paper vestments – was then tossed into the ceremonial fire with all the possessions of the deceased. In essence, the Nahua tradition of shrouding a corpse was a protective measure, meant to ensure the soul’s safe passage in Mictlan by wearing the appropriate symbolic garments necessary to appease the deities. For doña María, a Nahua-Christian dying seventy years after Spanish contact, requesting a Franciscan habit meant she would have an advocate in heaven much as she would have been protected from the perils of the under-world in a pre-conquest burial shroud.

A shrouded corpse properly prepared for the (possibly lengthy) journey to multi-layered Mictlan, Land of the Dead.

Detail of a mural by Antonio González Orozco, Hospital de Jesús Nazareno, Mexico City

In addition to being properly attired for Mictlan, Nahua tradition also specified a particular burial location based on one’s status or cause of death. For example, women who died in childbirth and drowning victims were not cremated but buried directly, for their destination was not Mictlan. For everyone else, however, the ashes would be buried in homes, temples, oratories, or at the bases of mountains. Tlatoque (singular: tlatoani) or Nahua leaders, had the right to be buried in front of the image of Huizilopochtli, the Mexica war god, at the base of the Huey Teocalli, or Great Temple. As a high-ranking native person, doña María’s ancestors may have been buried in places of honor inside or at the base of a temple, possibly the Quetzalcoatl Sanctuary, now replaced by a new sacred structure – the church of San Gabriel. For doña María, then, being buried in Cholula’s principal Catholic church would have resonated with her indigenous past, for as a high-ranking Nahua she would have deserved a prestigious location for her burial.

Is it any wonder that native peoples throughout colonial Mexico embraced the Christian practice of burial in the church or the camposanto? This is especially true because in the Spanish colonial world, even a poor, humble macehualli – or indigenous commoner – could find him or herself buried in the polity’s premier sacred structure, the analogue to the pre-conquest temple that had once been reserved only for burial of the indigenous elite. In the same way, native peoples wrote testaments, since it allowed the poor to achieve an equal status with the rich. (Cline, “Molina’s Model Testament,” 25).

But what of doña María Tlaltecayoa? Though her Christian faith may have motivated her to request a Franciscan habit as burial dress, its meaning may have been multi-layered for her. Rather than function merely as a symbol of her rejection of the world, it may have also served – like the tequimillolli shroud of her Nahua ancestors – to protect her soul as it entered the unknown, the Christian afterlife for which there had not been a word in her language, much less a concept. Like the paper vestments with which the pre-conquest corpse would be adorned during the miccaquimiloa ceremony, the Franciscan habit functioned as an apotropaic device meant to appease the God she would encounter in her soul’s journey through heaven, purgatory, hell – or Mictlan. By wearing the symbolic attire of a representative of God, doña María knew that the perils of the underworld would not affect her, and that she would safely reach her resting place in the afterlife. By merging her two identities, she created for herself a spiritual cloak with both Christian and Nahua fibers.

Whereas to the friars, to her Castilian husband, and to even to herself, she may have appeared to be following strictly-mandated Christian death ritual, her reasons for requesting a habit may have been more nuanced. Although the available materials do not allow us to speak definitively in this matter, it appears that by adhering to the Christian practice of burial in a Franciscan church wearing a Franciscan habit, doña María operated seamlessly within both of her spiritual and cultural traditions, re-imagining an afterlife that took into account her complicated identity as a Nahua-Christian.

[1] We have at least one example of a Spanish-language testament from a colonial native woman in the Toluca region whose ability to speak Spanish is undeniable. This 1703 will states: “Even though she is competent in Castilian… he executed the office of interpreter.” See Miriam Melton-Villanueva, “On Her Deathbed: Beyond the Stereotype of the Powerless Indigenous Woman,” in Documenting Latin America: Gender, Race, and Empire, ed. Erin O’Connor and Leo Garofalo (Prentice Hall, 2011), 171.