For those of us who are American, today is the Fourth of July: a day for fireworks, family, and celebrating (or reckoning with) the history of the United States of America. I have to admit, as a scholar of medieval history, I was tempted to ask a scholar of American history to write today’s post! Many scholars would say that nationalism as we think of it today didn’t exist during the Middle Ages. But after some thought, I wonder if a longer view of the history of the relationship between nation and faith might help us navigate a very modern conversation about Christian nationalism.

Christian nationalism, for those who are not familiar with the term as it’s generally currently used, refers to more than just being a Christian who is also a patriotic member of a nation. While there are heated debatesabout what the term is or isn’t, it broadly refers to the idea that America was founded as a Christian nation, and that the government should pass laws and act to bring the legislation and government of the US in line with “Christian” principles. Sociologists Samuel L. Perry and Andrew L. Whitehead have studied Christian nationalism extensively in their book Taking America Back for God, laying out six principles that define the movement along with the ramifications of these when put into practice. Now, I use “Christian” in quotes here because this is one of the tricky parts about Christian nationalism: no one quite agrees on what Christian principles are or should be.

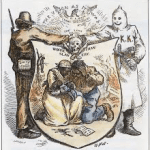

Others are certainly more qualified to discuss the relationship between Christianity and America’s founding or the complicated intersections between faith and politics in modern American history. But as a medievalist, I can’t help but notice some of the similarities between the language of blessing and defense of faith used in the modern Christian nationalist movement and the language used during the Crusades, a series of wars fought over the sites significant to the biblical narrative, particularly Jerusalem. What can we learn about our modern moment from looking at the medieval past?

The Crusades: Medieval Christian Nationalism?

The First Crusade started in 1095, launched officially by a speech from Pope Urban II at the Council of Clermont, a gathering of religious and secular leaders to address issues of church reform.

Multiple versions of the speech exist, recorded as many as twenty years after the original address, but the version recorded by Robert the Monk most explicitly connects national history, faith, and militant expansion. First, Urban II repeatedly sets Western Europeans apart as a group “chosen and beloved by God” and “set apart from all nations.” He encourages his audience to think of themselves as uniquely chosen to protect the church and the faith against “a generation forsooth which has not directed its heart and has not entrusted its spirit to God” (Robert the Monk, Historia Hierosolymitana, as quoted here). Second, Urban II urges medieval Christians to:

Let the deeds of your ancestors move you and incite your minds to manly achievements; the glory and greatness of king Charles the Great, and of his son Louis, and of your other kings, who have destroyed the kingdoms of the pagans, and have extended in these lands the territory of the holy church. Let the holy sepulchre of the Lord our Saviour, which is possessed by unclean nations, especially incite you, and the holy places which are now treated with ignominy and irreverently polluted with their filthiness. Oh, most valiant soldiers and descendants of invincible ancestors, be not degenerate, but recall the valor of your progenitors ((Robert the Monk, Historia Hierosolymitana).

Urban II, reminding his listeners that “God has conferred upon you above all nations great glory in arms,” urges them to go forth and conquer Jerusalem for God and for the remission of their sins.

Several elements of this speech sound like they could fit into modern campaign speeches or social media posts. The idea of a nation as uniquely chosen by God and as set apart to help bring about the spread and preservation of the faith, the encouragement to look to the past to see models of this sort of melding of faith and politics, the framing of past national leaders as heroes of the faith: plainly Christian nationalism has used the same sort of tactics to encourage the melding of state and church for at least a thousand years!

Faith and Fear

I think there’s one more important similarity to note here before we turn to some conclusions: the use of fear and imagined common enemies to centralize power and end internal conflict. In 1095, Europe was in the midst of a time of turmoil, as kings and nobles fought against each other to try to stabilize their kingdoms, expand their borders, and eliminate their enemies. This created problems for the church, as the constant infighting made it difficult to spread the faith, educate the laity, or really do anything! So, in encouraging the First Crusade, Urban II also encouraged an end to the fighting within Europe. He called the knights, kings, and nobles to respect the authority of the church, enforce peace among Christian leaders, and turn their attention towards being soldiers for God, fighting against enemies in the East rather than each other. Through pushing Europeans to imagine themselves as warriors for God fighting a common foe, Urban II helped increase the power of the Catholic church as well as lessened challenges to the power structures already in place within Europe.

It’s worth noting that Urban II did this largely through sensationalized and fear-filled language, referring to the persecution and execution of Christians, attacks on the faithful of God, and the desecration of holy places. Most of this wasn’t true: yes, Jerusalem was under Muslim rule, but it had been for quite a while, and both Christians and Jews had freedom to practice their religions. Furthermore, even during the Crusades themselves, there was sometimes coexistence and tolerance between the three different religions. But Western European sources hide these historical facts. Instead, by creating a monstrous “other,” Urban II solidified his own position and solved the challenges to the European status quo.

Past and Present

In thinking about what we can learn from this medieval example of Christian nationalism, I think it’s worth noting the damage that the Crusades did to the witness of the church. Whatever the articulated reasons for the Crusades, the indiscriminate slaughter and greed that often characterized their execution has been one of the dark stains on church history and a continuing point of tension today. And although there are clear differences both in the context and the events of this part of the medieval past and our own present political and cultural framework, I wonder if sometimes, in the no-holds-barred world of American politics, we are setting ourselves up for similar criticism from future generations. Are we massacring victims in a culture war of our own creation, killing imagined enemies in defense of a flawed understanding of protecting the faith? As Christians, we are called to spread the gospel, yes, but should that be through the political structures and models of our time? I think, looking at the teachings of Jesus in the Gospels, the answer to that is no. We are in this world, and in this nation, but not of it, which means that patriotism, nationalism, and faith should look distinctively different for us. We can be involved in government and politics, and we can advocate for what we believe is right, but I think we need to be careful to not make nationalism the priority rather than the gospel, which transcends nations and political divisions. As a general rule of thumb, maybe if we can see parallels between modern political arguments and Urban II’s crusade speech, it’s a sign that we should correct course and refocus not on power but on Christ.