On May 3, 1973, the body of J. Edgar Hoover lay in state in the Capitol Rotunda. The coffin holding the long-time FBI chief rested on the catafalque that had held Abraham Lincoln’s coffin over a century before. President Richard Nixon intoned, “Today is a day of sadness for the American people. America’s pride has always been in its people . . . of great men and women in remarkable numbers, and once in a long while, of giants who stand head and shoulders above their countrymen, setting a high and noble standard for us all. J. Edgar Hoover was one of those giants.” And he invoked the words of Scripture: “Great peace have they which love thy law.”

It was a dignified scene. And completely misleading.

The President and the FBI chief had a terrible relationship. Nixon privately called Hoover “that old c _ _ _ sucker.” And outside the Capitol Building, chaos reigned. Rumors began to spread that 500 long-haired antiwar protesters were planning to storm the Capitol Building and desecrate Hoover’s coffin. In response, Nixon enlisted the help of one of his henchmen: Roger Stone.

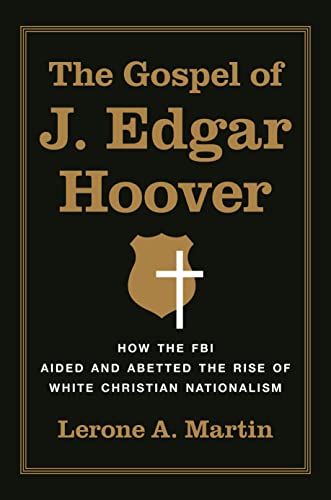

I promise I’m not making this up. I got it from the epilogue of historian Lerone Martin’s terrific book The Gospel of J. Edgar Hoover: How the FBI Aided and Abetted the Rise of White Christian Nationalism.

Yes, the same guy who formed Stop the Steal and threatened “Days of Rage” if Republican leaders denied Trump the nomination. The same guy who threatened to publicly disclose the hotel room numbers of delegates who worked against Trump. The same guy who said that if Trump lost the 2020 election, he should consider declaring martial law and confiscate ballots in Nevada. The same guy who said he had “learned of absolute incontrovertible evidence of North Korean boats delivering ballots through a harbor in Maine.”

Yes, the same guy who formed Stop the Steal and threatened “Days of Rage” if Republican leaders denied Trump the nomination. The same guy who threatened to publicly disclose the hotel room numbers of delegates who worked against Trump. The same guy who said that if Trump lost the 2020 election, he should consider declaring martial law and confiscate ballots in Nevada. The same guy who said he had “learned of absolute incontrovertible evidence of North Korean boats delivering ballots through a harbor in Maine.”

These sordid activities, it turns out, are nothing new. As Hoover’s body lay in state back in 1973, Stone organized a staged counterdemonstration. It was just the latest in the young man’s questionable political activities. Stone, a student at George Washington University, had left college the year before to work for Nixon’s reelection campaign (CREEP). He was officially hired as a “scheduler,” but one of his first assignments was to contribute money to one of Nixon’s rivals in the name of the Young Socialist Alliance and then slip the receipt to a newspaper in New Hampshire before that state’s primary. He also spied on rival presidential campaigns. By day he might be a scheduler. But “by night, I’m trafficking in the black arts,” he bragged.

For Lerone Martin this incident–in which discourses of religion and power and violence and any-means-necessary-politics intersect–captures the persistent reality of “white Christian nationalism in the nation’s body politic.” You can draw a pretty straight line from Trump backward to Hoover and Nixon through Stone.

It’s a counterintuitive argument, especially since white Christian nationalism has been so closely associated with evangelicalism. After all, Hoover (like Trump now) wasn’t an evangelical himself. He grew up a Presbyterian of the mainline variety. He never gave a testimony of conversion. And he cooperated closely with Catholics in an era when evangelicals didn’t do that.

Martin’s case for the Hoover being such a foundational figure rests on the thick ties he nevertheless cultivated between the FBI and midcentury white evangelical institutions, especially Christianity Today.

The relationship began when editor Carl F. H. Henry read Hoover’s 1958 Masters of Deceit: The Story of Communism in America and How to Fight It. The immensely popular book topped the bestsellers list for ten weeks in a row. It sold 250,000 hardback copies and then two million in paperback.

A Cold Warrior himself, Henry published a summary of Masters of Deceit as the lead article in the March 1958 issue of Christianity Today. Then he asked Hoover to write a stand-alone article for the magazine. Henry wrote Hoover, “No other journal has the access to the Protestant ministry that Christianity Today does, and it would please us immensely to carry a forceful essay from your pen at this strategic time.”

Hoover complied—mostly. He enlisted Special Agent Fern Stukenbroeker to ghostwrite the article, just like with Masters of Deceit, also written by Stukenbroeker under Hoover’s name. The article—entitled “The Challenge of the Future”—said that youth crime and communism threatened the soul of the nation.

It was a big hit, and so the collaboration continued. Five articles “by” Hoover proceeded between 1958 and 1960. Each one was immensely popular and said that America was God’s chosen nation. One title insisted that Americans had to make a choice between “Communist Domination or Christian Rededication.”

These articles did exactly what Henry had hoped. They suggested that the FBI and the Department of Justice were lending their authority to the fledgling magazine and the young neo-evangelical movement it spoke for. After the essays were published, the FBI even reprinted them on Department of Justice letterhead with the FBI emblem.

As is always the case when church-state lines are blurred, it’s not just the church using the state. The state uses the church. With a circulation almost five times that of the National Review, Christianity Today was a fertile field for FBI recruitment. It ginned up Cold War anxiety and reinforced the power of Hoover and the security apparatus.

This relationship, according to Martin, cemented the place of Christian nationalism within white evangelicalism. It became not just a bug, but a feature.

Martin is quick to offer a qualification: It wasn’t just white evangelicalism. The same dynamics were at play within mainline Protestantism and American Catholicism. Hoover had a very tight relationship with Jesuits.

But it does explain recent evangelical realities. First, it makes evangelical support for the decidedly non-evangelical Trump more intelligible. There was a precedent in Hoover. Christianity Today praised his “legendary stature.” The Pentecostal Evangel lauded his Christian witness. In the end, the gymnastics required to make Hoover (and Trump) palatable, says Martin, are really just evidence for an evangelical practice of any-means-necessary politics. He writes, “This pragmatic ‘ends justify the means’ ethos is the very cunning creativity that led to the collaboration with J. Edgar Hoover and his FBI, and it remains a robust tradition within the movement. White evangelicals remain willing to compromise their stated morality and theology in exchange for the maintenance of whiteness and access to political power, all to bring America back to their God.”

Second, as suggested by Martin in the quote above, Hoover implicates evangelicalism on race. “Hoover’s gospel was focused on the individual soul,” he writes. “The best way to fix America’s race problem was not violence, protest, or legislation. Rather, individual and group piety was the best way for Black Americans to earn white respect and the eventual prize of equality.”

That’s the less toxic version. Martin shows that some evangelicals nodded right along (or looked the other way) when Hoover bullied and threatened Martin Luther King, Jr. When Hoover said that civil rights legislation (the 1964 Civil Rights Bill and the Voting Rights Bill) was the result of a coalition of “bleeding heart” judges and politicians. When he used extralegal measures to surveil and violate the civil rights of college students, Black activist organizations, and antiwar protesters. When he called King’s nonviolent activism “anarchy” and “a disservice to his own race and our country.” And when he confessed that “the thing which has irritated me more than anything else has been the unreasonable demands of the extremists of the right and left—the Klan on the right, and Martin Luther King on the left.”

Sound kind of familiar? History may not repeat itself, but it sure does rhyme.