Jonathan Edwards is best known for his evocative description of hellfire. In “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” (1741), Edwards intoned, “This is the case of every one of you that are out of Christ: That world of misery, that lake of burning brimstone, is extended abroad under you. There is the dreadful pit of the glowing flames of the wrath of God; there is Hell’s wide gaping mouth open; and you have nothing to stand upon, nor anything to take hold of; there is nothing between you and Hell but the air.”

It was said that his listeners screamed in terror. Edwards had to stop several times to ask for silence.

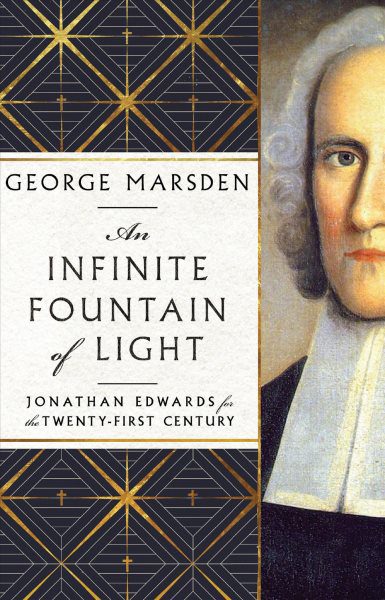

This sermon certainly happened, says historian George Marsden, but it was not representative. In his just-published book, An Infinite Fountain of Light: Jonathan Edwards for the Twenty-First Century, Marsden says that a much-less read sermon—“A Divine and Supernatural Light” (1733)—better captures the thrust of Edwards’s larger oeuvre. That sermon emphasized beauty and love. Edwards, contends Marsden, believed that the universe was, most essentially, a beautiful expression of God’s love. Edwards preached, “God is God, and to be chiefly distinguished from all other beings, and exalted above them, chiefly by his divine beauty.” He continued, “God’s light and love flow forth, that the infinite fountain of good should send forth abundant streams, that this infinite fountain of light should, diffusing its excellent fullness, pour forth light all around.”

This sermon certainly happened, says historian George Marsden, but it was not representative. In his just-published book, An Infinite Fountain of Light: Jonathan Edwards for the Twenty-First Century, Marsden says that a much-less read sermon—“A Divine and Supernatural Light” (1733)—better captures the thrust of Edwards’s larger oeuvre. That sermon emphasized beauty and love. Edwards, contends Marsden, believed that the universe was, most essentially, a beautiful expression of God’s love. Edwards preached, “God is God, and to be chiefly distinguished from all other beings, and exalted above them, chiefly by his divine beauty.” He continued, “God’s light and love flow forth, that the infinite fountain of good should send forth abundant streams, that this infinite fountain of light should, diffusing its excellent fullness, pour forth light all around.”

It wasn’t just heady doctrine and pretty words. Edwards felt it. He experienced it, particularly on horseback rides through the countryside on lovely days. That’s the context for this passage—and many other passages—in his collected writings:

So that when we are delighted with flowery meadows and gentle breezes of wind, we may consider that we only see the emanations of the sweet benevolence of Jesus Christ; when we behold the fragrant rose and lily, we see his love and purity. So the green trees and fields, and singing of birds, are the emanations of his infinite joy and benignity; the easiness and naturalness of trees and vines are shadows of his infinite beauty and loveliness; the crystal rivers and murmuring streams have the footsteps of his sweet grace and bounty (“The Miscellanies,” 1722).

He also experienced God’s beauty in relationships. In an early devotional, the romantic Edwards wrote of his wife Sarah, “When we see beautiful airs of look and gesture, we naturally think the mind that resides within is beautiful. We have all the same, and more, reason to conclude the spiritual beauty of Christ from the beauty of the world, for all the beauties of the universe do as immediately result from the efficiency of Christ, as a cast of an eye or a smile of the countenance depends on the efficiency of the human soul.”

Yes, there is death. Alongside fragrant roses, Edwards saw rotten carcasses on his rides through the meadows. There is human depravity. There is the possibility of hell, which he spoke so evocatively about in “Sinners.” But these realities should not dominate theological discourse. As Marsden puts it, “Unlike what it often seems in the bleak, materialistic world, evil does not reign.”

Marsden, like Edwards three centuries earlier, mourns the dominance of modern materialism. He contrasts Edwards to Benjamin Franklin, Edwards’s contemporary, whose materialist assumptions obscured transcendence. He also nods to Charles Taylor, who more recently has observed that an immanent frame encourages us moderns to perceive reality as made up of essentially impersonal forces.

But these impersonal forces are in fact personal. Marsden writes that “without God’s creative power sustaining the universe, things would cease to exist.” He continues, “For Edwards, the dynamics of the physical universe were to be understood and admired most essentially as beautiful expressions of the love of their Creator and Sustainer. And not just in the gaps, but everywhere.” Material things express God’s loving beauty.

This truth, Marsden concludes, should change how we live. God’s beauty should drive our actions. “The Christian will love what God loves,” wrote Edwards. Marsden further notes that Edwards often cited Colossians 3:12-13, in which St. Paul urges “mercies, kindness, humbleness of mind, meekness, longsuffering, forbearing . . . and forgiving.” Edwards also loved to cite a parallel passage in Galatians 5, which catalogues the “fruit of the Spirit”: love, joy, peace, longsuffering, gentleness, goodness, faith, meekness, temperance. The “lamblike, dovelike spirit and temper of Jesus Christ,” wrote Edwards, are fundamental Christian traits.

Clearly this is not just a book of historical recovery. In the vein of Marsden’s memorable “Concluding Unscientific Postscript” in The Soul of the American University (and his follow-up The Outrageous Idea of Christian Scholarship), this book gives spiritual advice. He gets prescriptive as he excavates Edwards on beauty and rightly ordered living. Indeed, this is the main project. “My central argument,” he writes, “is that Edwards’s core vision . . . has much of value to offer for renewal today.”

That vision differs dramatically from the so-called “theobros.” These self-appointed defenders of the faith often use their hero Edwards toward angry-God ends, to reinforce hierarchy, to emphasize divine judgment, to bolster a John Wayne-style ends-justify-the-means masculinity. Marsden writes, “Some of those who have most celebrated Edwards have also celebrated manly militancy in ways that are contrary to what Edwards sees as one of the fundamental qualities of a genuine child of Christ.” Even “most evangelical churches” seldom emphasize humility, love, and gentleness as evidence of being “born again.”

What’s so compelling about Marsden’s critique is that he practices what he researches. He says hard things with gentleness. That’s no surprise to those who have read his books and essays (like this one for an organization that has sometimes sheltered theobros). It’s also no surprise to those who know and love George in real life. As my doctoral advisor, he gently said hard things about my dissertation!

I’ll leave him with the final word. It’s true that “we are lost, feeling our way in a world of dark shadows.” But it’s also true that God’s transforming love is beautiful—that we, as the book’s last line says, “have the potential to become exquisitely wonderful flowers nourished by the sun.”