Today we welcome Dr. Michel Sun Lee, an Assistant Professor of History and Political Studies and Director of the Southern Scholars Honors Program at Southern Adventist University.

Today we welcome Dr. Michel Sun Lee, an Assistant Professor of History and Political Studies and Director of the Southern Scholars Honors Program at Southern Adventist University.

People sometimes ask, “What’s the most shocking thing you’re finding these days while doing research?” Just as often, I am bereft of a quick response. As any historian will attest, archival research and crafting a narrative can be ploddingly slow and sound even more so when described to those who don’t spend their time combing through nineteenth century church minutes.

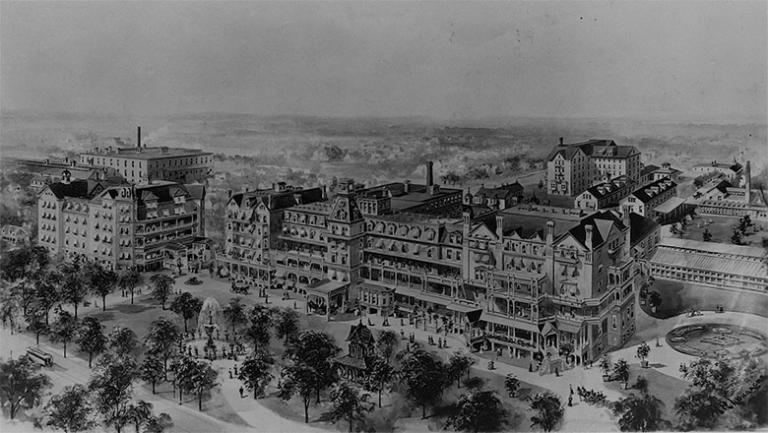

In the absence of discovering any gilded skulls in the archive that I suspect would garner the response I crave from non-historians, it feels rewarding when I do find stories related to my research about North American sacred timekeeping practices that excite them. One that has been particularly resonant when speaking to audiences in my faith community, Seventh-day Adventists, is the story of a Methodist woman who became a national leader in the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) in the 1870s. Decades later she joined the newly formed Seventh-day Adventist denomination after being cured at John Harvey Kellogg’s 19th c. medi-spa, the Battle Creek Sanitarium.

Having newly adopted convictions about keeping the seventh day sacred, she began to experience a great deal of discomfort about her post in the WCTU. At the time, the WCTU actively pursued the passage of legislation mandating Sunday observance, working with Sunday champions like Wilbur F. Crafts, who had a notorious dislike of Adventists. These efforts lay in direct opposition to the Adventist woman’s newly minted convictions and initiated a crisis of conscience. At one point, she seriously contemplated resignation from the WCTU altogether.

I’ll talk about how race figures into all this at the end of the blog post. But first: I think Adventist audiences resonate with this story because they too find themselves sitting in the tension of being minorities within a larger religious majority. I doubt R. Laurence Moore’s assertion that there was an “eventual complete accommodation of Adventism to the ‘American way of life.’” In North America, Seventh-day Adventists honor the Sabbath by stopping work, school, commercial activity, and/or other practices on Saturdays, which puts them at odds with Sunday-keeping Christians and the regular machinations of a Sunday-ascendant society.

An example: the SAT is normally administered on Saturdays. When I took it, I was able to register for accommodations that allowed me to take it on a Sunday. But I still had to drive 2.5 hours to a testing center that opened on Sunday, as opposed to a five minute trip to the local high school. And many Christians I meet have never heard of Christians who observe a seventh day, which adds to the awareness of being in a minority.

Historically, seventh day observant Christians seem to have more in common with Jewish Americans than they do with fellow Christians. Both were among those prosecuted for refusing to honor Sunday rest throughout the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries. In Tennessee, where I teach now, Adventists were placed in chain gangs for operating businesses on Sundays in the 1800s. (Of course, it needs to be said that Jewish and Adventist sacred time observances and beliefs also diverge in dramatic ways.)

Other Adventist practices and beliefs have set the community apart from the American Christian mainstream. They have hesitated to be involved in American politics, a far cry from the political alliances into which evangelicals have entered. To this, I add the denomination’s endorsement of vegetarianism and avoidance of pork, alcohol, and caffeine—which means that many Adventists do not eat the way that other American Christians eat, historically and in the present. This difference has generated various judgments over time.

In other ways, though, seventh day observant Christians are very much like other American Christians in 2023. While it is an incredibly racially and ethnically diverse denomination, some Adventists’ political and ideological alignments look like the most problematic parts about American evangelicalism today. They listen to Christian music, read Christian books, and hold church services that look like those of other American churches. And of course, if asked if they are Christians, Adventists will answer yes, which subjects them to both the privileges and pitfalls of identifying as such in twenty-first century America.

In some ways, it seems that Adventists are living in a version of their nineteenth century temperance paradox: they participated in a large movement led by White evangelicals (temperance), while also evidently feeling quite on the fringes of that very movement (conflicts with temperance and other moral reformers over the issue of Sunday observance). Certainly, Adventists who are observant in the ways described above do not wish to be other than they are. Nevertheless, my recent research forays have led me to some navel-gazing about how “minority” is an elusive and fragile concept.

Three days ago, a man asked me, “But where are you really from? Because you don’t look American.” I am Asian American, which means that I am part of a racial and ethnic minority in many parts of North American society. Backing discrimination and prejudice in the present day is a long history of racism directed at Asian and Asian-descended people in the United States. I am also part of a minority denomination whose history I have briefly detailed above.

The example of the WCTU woman isn’t really instructive about race in America. But it sure does raise questions for me as a historian of religion, as a person of faith, and as a person of color. Does the fact that I am a seventh day observant person who is a person of color snowball intersectionally into a double minority status? Or am I somehow both in minorities and majorities? What does it mean that I can give voice to those who have experienced the tensions of being a religious minority, while at the same time are part of a historic religious majority?

Exploring these intersections is a task for another time. For now, these are questions that I am ploddingly working through in the archives and in my everyday thoughts, gilded skulls or not.