This is the first of two Halloween offerings from me this year.

Earlier this year I published a book on the reception of Psalm 91 through history: this was my He Will Save You from the Deadly Pestilence: The Many Lives of Psalm 91 (Oxford University Press). Over the past couple of millennia, that psalm has enjoyed a robust career as a protection against demons and evil forces. Depending on the translation, it has multiple references to evil forces, both literal (pestilences) and spiritual. In modern times, the psalm has enjoyed a whole new history as an inspiration for some impressive horror and Gothic fiction, which seems uniquely suitable for a Halloween post. If you are looking for seasonal reading, I will especially recommend one wonderful contribution, by E. F. Benson, “Negotium Perambulans.”

Fiction of all kinds often borrows Biblical phrases for titles or motifs in stories, but the Psalm 91 instance is notable because authors deliberately cite it in archaic ways, often in the Latin Vulgate. By doing this, they are deliberately trying to put the reader back into an imagined Middle Ages. They use demonic-sounding phrases, such as the daemonium meridianum, the Noonday Demon, which the King James renders as “the destruction that wasteth at noonday.” Also popular was the cryptic phrase that in English appears as “the pestilence that walketh in darkness.” In Latin that becomes the almost comically non-specific negotium perambulans, which comes close to referring to a wandering thingumajig.

One early example of such a usage was “The Botathen Ghost” (1867), by the once-famous English author R. S. Hawker. In his tale, a seventeenth-century clergyman who encounters the ghost of a woman is alarmed because she “might be a daemonium meridianum, the most stubborn spirit to govern and guide that any man can meet and the most perilous withal.” He duly exorcizes the presence, but not before she has fulfilled another task closely linked to the psalm, prophesying the great plague that would assail London in 1665. The cleric’s citation of Psalm 91—and in the outdated Latin—deliberately consigns the tale to a rural and superstitious past, impossibly remote from modernity.

Like many successors, Hawker used the Vulgate to medievalize the psalm and its thought-world. In 1895, the celebrated writer of supernatural tales M. R. James published the story “Canon Alberic’s Scrap Book,” one of his most popular creations. It imagines a seventeenth-century French cleric who records his encounters with the terrifying night demon that will soon claim his life. As Alberic approaches doom, he tries to invoke the powers of holiness, which naturally involves the psalm that he refers to under its Vulgate title of “Qui habitat.”

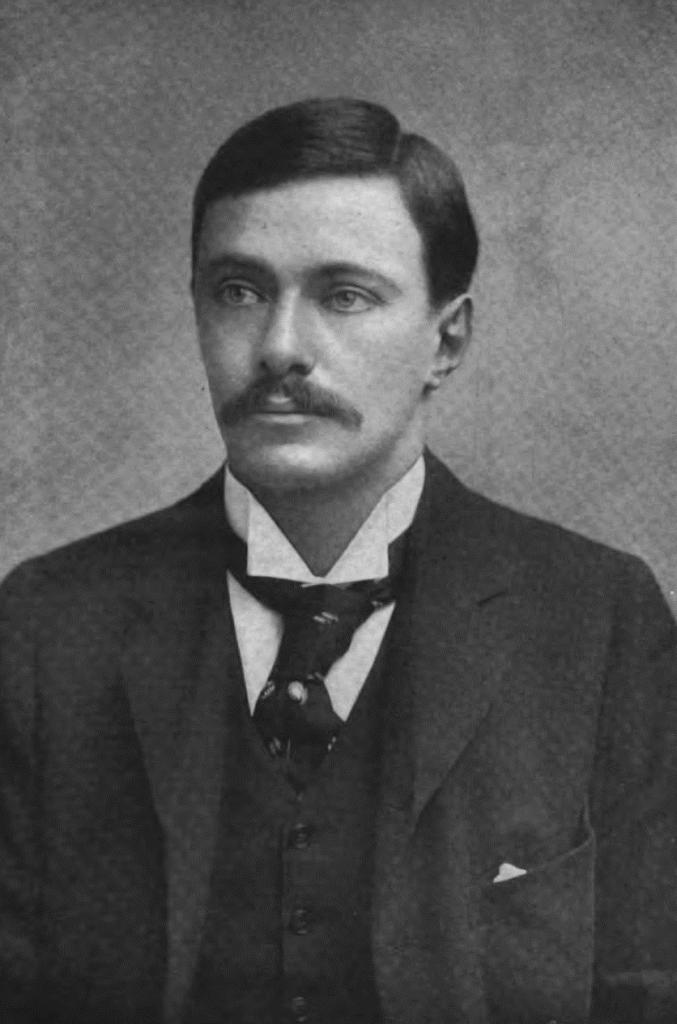

Particularly evocative was the idea that those older demonic forces could somehow, mysteriously, manifest into the modern world of science and reason. One of James’s rivals in the world of horror and fantastic fiction was E. F. Benson, scion of a great Anglican clerical dynasty. In 1912, he borrowed Psalm 91’s “The Terror by Night” as the title for a horror story, but his finest achievement came a decade later with his classic “Negotium Perambulans.” Benson’s story involves sinister paintings on the panels in an ancient church, which depicted a priest confronting a hideous monster:

Below ran the legend “Negotium perambulans in tenebris” from the ninety-first Psalm. We should find it translated there, “the pestilence that walketh in darkness,” which but feebly rendered the Latin. It was more deadly to the soul than any pestilence that can only kill the body: it was the Thing, the Creature, the Business that trafficked in the outer Darkness, a minister of God’s wrath on the unrighteous.

The psalm is used to suggest spiritual warfare in medieval times, the surprise being that those evil forces might in fact be dormant rather than dead. “Negotium Perambulans” is still a staple of vampire fiction anthologies (and here it is, full text). H. P. Lovecraft highlighted it as the best of “several stories of singular power” in Benson’s collection.

Benson was far from alone in his use of such consciously archaic references. When in 1929 Montague Summers published The Vampire: His Kith and Kin, which affected to take all such medieval lore with deadly literalism, the book’s epigraph was our psalm’s vv. 4–5, and of course, in the Vulgate.

Such invocations of the archaic past were by no means confined to the Gothic, strictly defined. In 1934, F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote a much-anthologized essay, “Sleeping and Waking,” for Esquire. He addressed the wakeful hours in the middle of the night, “a sinister, ever widening interval” between the early and later spells of comfortable sleep. “This is the time of which it is written in the Psalms: Scuto circumdabit te veritas eius: non timebis a timore nocturno, a sagitta volante in die, a negotio perambulante in tenebris [91:5–6].” He recalled the Vulgate text from his Catholic upbringing, but here he is offering it (untranslated) to a magazine audience that would find it exotic and even exciting, and that is the point. In the King James, the text reads:

His truth shall be thy shield and buckler. Thou shalt not be afraid for the terror by night; nor for the arrow that flieth by day; Nor for the pestilence that walketh in darkness

At these darkest times of night, he suggests, we enter a realm of fantasy and unrest that had traditionally been understood as sinister and demonic. He represents that not just by quoting the Bible, but by using the form in which it would have been quoted in the superstitious Middle Ages—although obviously we moderns understand these terms in completely non-supernatural ways. However humorous and self-deprecating the tone of the essay, the psalm offers an ideal way to discuss those primitive concepts in a rational modern world. By this point, many of his readers may have recognized the Latin words from their frequent invocation in horror and Gothic fiction.

I think that sets us in a mood for Halloween, does it not? More tomorrow.

I should explain one oddity this week. Normally, I blog once a week at Anxious Bench. However the powers that be at the blog rearranged matters to open up some slots for new faces, which is a worthy goal. As a result, I will be posting a block of items all at once, which means that I will have five posts – count them, five – in this coming week. Weird, I know, but bear with me!