Twenty-one percent of white mainline Protestants do not believe in the virgin birth of Jesus, a Pew research survey found. By contrast, only 1 percent of white evangelical Protestants say they don’t believe this story.

This division among Protestants over the virgin birth, as well as other biblical miracles, is not new. For more than a century, American Protestants have been debating these questions – and for more than a century, some seminary and college professors of the New Testament have said that the historical evidence does not support the facticity of the virgin birth or other traditional beliefs of the church.

Those who don’t believe often cite the evidence of historical criticism of the Bible as a reason to assume that stories such as the virgin birth were early Christian legends that developed over the course of several decades rather than factual accounts based on first-hand testimony. Theologically conservative Christians who continue to believe in the virgin birth or the resurrection are ignoring the historical evidence, they claim.

Yet on closer inspection, it seems that this claim is based on philosophical assumptions rather than historical evidence. In fact, when American college professors of the New Testament first encountered historical criticism of the gospels in the early nineteenth century, they rejected it on the grounds that the evidence for it was lacking. It was only a half century later, after they had acquired a new philosophical framework, that they accepted historical criticism of the Bible. The evidence for (or against) historical criticism of the Bible had not changed, but their view of it did, because their philosophical frame of reference had shifted.

Historical criticism of the Bible (that is, the attempt to reconstruct the history of a biblical text’s formation and examine it as a product of a particular historical era) began at least as early as the late seventeenth century, when the skeptical Dutch Jewish philosopher Baruch Spinoza critically examined the Torah and concluded that there were at least some parts that Moses could never have written, since they described events that occurred after his lifetime. He could never have written the last chapter of Deuteronomy, for instance, since it describes his own death.

Spinoza’s work influenced several British deists, who repeated some of his arguments, and it also sparked critical study of the Bible in France. At the end of the eighteenth century, German scholars began imitating some of his methods and expanding them into a scientific discipline that covered not only the Old Testament but also the New.

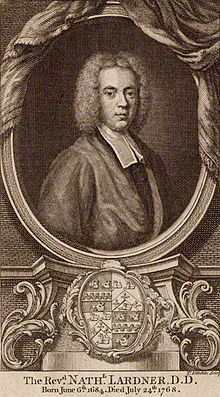

British and American college professors, ministers, and Christian apologists almost never referenced Spinoza or other practitioners of historical criticism of the Bible directly, but when they encountered the arguments of the historical critics through the writings of contemporary deists, they issued rebuttals that they thought were convincing. In the mid-eighteenth century, the Dissenting church minister Nathaniel Lardner wrote a 17-volume defense of the historicity of the four gospels that addressed every argument he could find against the historical accuracy of any episode of Jesus’s life recorded in the Synoptics or the gospel of John. He spent 86 pages on the census of Quirinius, ultimately concluding that while an empire-wide census in the year of Jesus’s birth was unlikely, there was no reason to believe that a local census in Judea had not occurred that year.

Lardner approached his project with different assumptions than the historical critics had. For Lardner, the question he faced with every recorded episode in Jesus’s life was: Is there anything in this biblical account that is impossible to reconcile with what I know from the other gospels and from extrabiblical sources from the ancient world? If the answer was no, the account should be believed, he thought.

But this was not the question that guided historical critics in early nineteenth-century German universities as they examined the biblical text. They did not ask whether the biblical accounts could be harmonized with information from other sources. Instead, they approached the text with a much greater suspicion of the miraculous than Lardner had had – and they believed that if miraculous accounts were legends, they must have evolved over the course of several generations.

Lardner was in many ways a liberal in his day. He was far more willing than his American contemporary Jonathan Edwards was to subject the Bible to the test of human reason. In his quest to weigh each episode in the gospels against the historical evidence from other sources, he was engaged in an Enlightenment project that Calvinist ministers of a previous generation would have been unlikely to attempt. But ultimately, he thought that the Bible could be harmonized with other sources, and that if that were the case, the Bible should be accepted as historically trustworthy until proven otherwise. Miraculous accounts should not be rejected a priori – and if they harmonized with other historical evidence and were based on eyewitness testimony, they should be treated as credible as long as the witnesses themselves were trustworthy.

This reflected the views of the two British philosophers who had the greatest influence on eighteenth and early nineteenth-century Anglo-American thought: John Locke and Thomas Reid. Locke believed that one could use reason to know God’s existence from the evidence from nature, and that one could likewise use reason to evaluate the evidence of the testimony of miracles contained in the gospels and know from that evidence that Jesus was a man like no other and that his message had a divine origin. Reid’s common-sense realist philosophy expanded on that argument with a lengthy philosophical defense of the legitimacy of evidence from testimony – an argument that was largely a refutation of the skepticism of David Hume, the eighteenth-century Scottish philosopher who rejected all testimonies of the miraculous out of hand.

The German historical critics of the early nineteenth century, by contrast, were not Lockeans or common-sense realists. Instead, they were Kantians and Hegelians. From Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), they learned that the realm of the spiritual was separate from the realm of reason; one could not use natural evidence to prove the existence of God or the reality of miracles, as John Locke had thought. From Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831), they learned that history was progressive, and that all of civilization – including religion – was evolving from more primitive to more advanced stages.

While early nineteenth-century American professors of the Bible were using comparative historical study of the text to demonstrate the historical credibility of biblical miracles, German historical critics of the Bible during the same period were dismissing these miraculous accounts as implausible on philosophical grounds and were embarking on a quest to determine the evolution of the biblical text using their Hegelian assumptions about religious and cultural progress. The best known of these Hegelian-inspired German critical scholars was David Strauss, whose The Life of Jesus, Critically Examined created an international sensation when it was published in the 1830s.

The New Testament gospel accounts – filled as they were with implausible accounts of fantastic miracles – were myths, Strauss argued, and myths take time to develop. The gospel accounts were therefore probably written in the second century, many decades after Jesus’s crucifixion.

Strauss’s book had an enormous influence in Europe. The skeptic Mary Ann Evans (better known by her pen name George Eliot) helped translate the work into English. In the United States, some of the Transcendentalists, such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, found the arguments of Strauss and other German historical critics persuasive.

But when Harvard New Testament professor Andrews Norton read Strauss’s argument, he was aghast at its lack of supporting evidence. Although he was a Unitarian who did not believe in biblical inerrancy, he did think that the historical evidence supported the general historical credibility of the gospels, including the gospels’ miraculous accounts. And he thought that there was no evidence at all for Strauss’s suggestion that the gospels could not have been written in the first century.

In the multivolume defense of the gospels’ historicity that Norton produced as a refutation of Strauss and other German critics, he pointed out that early second-century early Christian writers, such as Clement of Rome and Ignatius of Antioch, quoted from the gospels as authoritative apostolic sources. And if the early Christians were quoting from the gospels at the very beginning of the second century, they must have been produced no later than the late first century.

Because Kant and Hegel were mostly unknown in the United States at the time, most American scholars of the antebellum era saw no reason to dismiss credible historical testimony simply because of a philosophical assumption that miraculous accounts were legendary or that the accounts of Jesus’s life in the canonical gospels must have evolved over the course of several generations. Strauss’s book therefore had very little influence on college or seminary curricula in the United States when it first appeared in German in the 1830s or was translated into English in the 1840s.

But that changed in the late nineteenth century. After the Civil War, a new generation of American biblical scholars traveled to German research universities to study for a Ph.D., a degree that barely existed in the United States at the time. (The first Ph.D. in the United States was not granted until 1861, when Yale awarded the degree to three students). With the expansion of American higher education after the Civil War, there was a new interest in research degrees and in learning from the leading scholars in the world – which, in the case of biblical studies (as well as many other fields) meant studying in Germany.

The American students who traveled to Germany for graduate study learned not only the particular arguments of historical critics of the Bible but the larger philosophy of historicism – that is, the belief that history is progressive and that the present is very different from the past. They learned a Kantian separation of religious truth claims from scientific truth claims – and thus became suspicious of history that tried to blend the supernatural with the natural, as American biblical scholars had previously done when treating Jesus’s miracles as historical events. While there were a handful of holdouts, most of the American biblical scholars who studied in Germany in the late nineteenth century returned to the United States with a view of scripture that very closely paralleled the views of the German historical critics who had been universally dismissed by American educators in the 1830s and 1840s.

Yale church history professor George Park Fisher was dismayed at this development, because in his view, the evidence was still in favor of the Bible’s historicity – and especially the historicity of the gospels. In his Manual of Christian Evidences, published in 1892, he systematically demonstrated that the gospel writers were familiar with the language, customs, and geography of first-century Judea and Galilee. They could not therefore have been written much after the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE. The fact that the second-century Christians considered these works authoritative and apostolic must have meant that they had already been circulating in the churches for years by the beginning of the second century.

The only reason that people dismissed the historical evidence for the gospels’ early composition was because they found the miraculous accounts implausible, Fisher said. Because they insisted that the miraculous accounts were legends, they had to give the legends enough time to develop, which meant that they had to move the composition of the gospels to the second century, as Strauss had. But the objection to the miraculous was a philosophical, not a historical one, and in his view, it had already been conclusively answered in the eighteenth century, when Christian apologists were arguing against David Hume.

Hume’s “fundamental error consists in arguing the question on the tacit assumption of atheism. He ignores the existence of a cause adequate to work miracles, and, of course, the existence of any motive or occasion for them to be wrought,” Fisher declared. In other words, if one assumed the existence of a God capable of effecting miracles, and if one assumed that this God might have good reason to perform miracles at particular junctures in human history, one no longer had reason to dismiss testimonies of miracles out of hand – especially when dismissing these testimonies required one to ignore good historical evidence.

Christian apologists lauded Fisher’s arguments, but they did not influence many seminaries or college religion courses. Instead, with only a few exceptions, American Protestant colleges and seminaries in the early twentieth century embraced liberal Protestant assumptions about the Bible’s composition. They became wholesale converts to the type of historical criticism of the Bible that was taught in German research universities of the time.

Perhaps that was largely because the entire American research university model, along with the new discipline of historical criticism of the Bible, was an import from Germany, and German scholarship on the Bible was widely considered to be the best in the Western world. To repudiate the foundational assumptions of German scholarship would have called into question the entire discipline of critical biblical studies, as well as some of the fundamental assumptions of the modern research university. Few scholars at American research universities or research-oriented seminaries (such as the University of Chicago) were willing to do that.

Nevertheless, throughout the twentieth century, evangelical scholars pushed back against the critical views that defined the mainstream. In addition to repeating Fisher’s arguments, they also pointed to twentieth-century archaeological evidence that supported the historicity of the biblical text. Archaeological confirmations of the existence of Pontius Pilate and Caiaphas the high priest, along with several other figures mentioned in the gospels and the book of Acts, seemed to suggest that these books were composed by people familiar with early first-century Judea. Mid-twentieth-century Wheaton professor Joseph Free, for instance, was convinced that information about biblical archaeology was the best antidote to historical criticism of the Bible. In addition, new biblical manuscripts discovered in the twentieth century – such as the John Rylands Library’s fragment of the gospel of John, dated to the second century CE – made it seem highly unlikely that the gospels could have been composed much later than 100 CE, as Strauss had claimed.

Today even many liberal New Testament scholars who accept the assumptions of historical criticism believe that some or all of the gospels were composed in the first century, because the historical evidence for a first-century date for this material is too compelling to ignore. But the philosophical presuppositions against the historicity of the Bible’s miraculous accounts, along with the belief that the gospel accounts must have evolved over time (even if that time frame is now believed to be shorter than Strauss assumed) have continued. Bart Ehrman, for instance, continues to argue that the virgin birth and many other stories from the gospels are fictional legends – but because of the manuscript evidence for a first-century date for the gospels, he argues that these legends developed in the first century rather than the second, as Strauss had believed. Yet the belief that some or all of the miraculous stories of the New Testament are legends is rooted more in philosophical assumptions than in historical evidence.

In Britain some conservative scholars, such as N.T. Wright and Richard Bauckham, have won international recognition for scholarship that doesn’t rest on these philosophical assumptions – because they have shown that when we’re not tied to the philosophical assumption that Jesus could not have risen from the dead, the historical evidence for the countercultural nature of early Christian belief in the resurrection can raise fascinating questions that scholars who are tied to the philosophical presuppositions of nineteenth-century German scholarship might never think to ask. There is compelling textual evidence to indicate that at least some of the gospel accounts were based on the recollections of eyewitnesses, they argue.

Why does all of this matter? As we enter into the Christmas season this year, we may at some point be confronted by the question of how we can continue to believe in a literal virgin birth or a literal incarnation after so much critical New Testament scholarship has been produced casting doubt on all of those beliefs. For a while, I was troubled by those questions myself. But if I know that this scholarship was based not on a dispassionate reading of the historical evidence but on philosophical assumptions that I don’t have any reason to share, I’m not as likely to find those questions very troubling. There’s good historical reason to believe that the gospel accounts of Jesus were not merely legends or myths – provided, of course, that we’re not distracted by the philosophical presuppositions that led nineteenth-century German scholars to believe that they were.