Of all the holiday-themed romantic comedies that I consume in abundance this time of year, my favorite is Dash & Lily, a Netflix series about a budding romance between two teenagers who trade messages and dares during the Christmas season. There’s much to love about this series: its setting in the Strand (the best bookstore in the world) and in New York City (the best city in the world) during the holidays (the best season for cozy romantic comedies). But I especially love that it’s a show that features an Asian American heroine–Lily, a Japanese American teenager–who celebrates the holidays in a distinctly Asian American way, combining American Christmas traditions (caroling, hijinks involving the Santa Claus at Macy’s) with Japanese New Year traditions (making mochi, doing a family Oshogatsu ceremony at a Zen temple). As I argued in an Anxious Bench post I wrote back in 2020, Dash & Lily portrays a rich array of holiday rituals practiced by an increasingly multiracial and multireligious America and offers an opportunity to reflect on how Asian Americans do Christmas and New Year in distinctive ways.

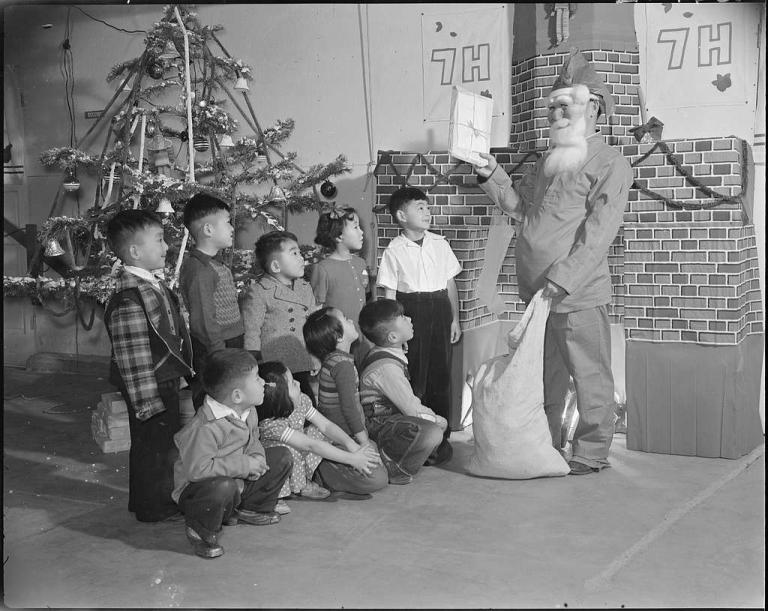

Today I revisit the theme of Asian American ritual life because we’re once again at the point of the year when I witness religiously diverse Asian Americans put values of pluralism and multiculturalism into practice and celebrate the Christmas and New Year in eclectic and creative ways. Asian American families who are Sikh, Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, and more often embrace Christmas with gusto, sometimes making the season’s rituals their own by merging them with their own religious traditions. NBC reported on how one Muslim South Asian American family, for example, created a “crescent moon-shaped Eid tree,” built gingerbread mosques, and embraced “Khadija, the first ever Muslim Elf on the Shelf.”

How do we make sense of these choices? New research offers some helpful context. This past year saw the release of two big reports about Asian American religious life–Exploring AAPI Experiences of Religious Identity and Diversity, a project by Interfaith America and The Asian American Foundation, and Religion Among Asian Americans, a report by the Pew Research Center–that suggest that the capaciousness, creativity, and combinatory character of Asian American holiday rituals is a feature of Asian American religious life more broadly. And while these reports are hardly the first effort to provide the general public with an overview of Asian American religious life–Pew, for example, published a large study about Asian American religion in 2012–the reports released this year mark a departure from previous work on the subject in a few main ways. For one, in recognition of the fact that so many Asian Americans are immigrants and have close ties to countries in Asia, the reports consider Asian American religious life through a transpacific lens and in relation to specific Asian cultural contexts. Rather than relying solely on surveys, they make space for Asian Americans to describe their religious life on their own terms through storytelling, interviews, and focus groups, methods that allow for a more complex and nuanced understanding of religious choices. Most significantly, they showcase how Asian Americans complicate the Western, Christian-centric understanding of religion that continues to shape the public conversation about religion in the United States. As the two reports reveal, Asian Americans embrace a religious and spiritual life characterized by multiple belonging, hybridity, and fluidity, as well as a skepticism and uncertainty about applying the label of “religion” to their beliefs, practices, and identities.

Asian Americans and the trouble with “religion”

Studying Asian American religion is a difficult undertaking because, as both reports explain, “religion” is a Western concept and a term that Asian and Asian American people do not always embrace, both in the context of the United States and Asian. In the Pew report, for example, the authors offer a lengthy discussion of the challenges of using the word to describe Asian beliefs and practices:

“In many East Asian languages, there is no single, literal equivalent of the English word ‘religion.’ The modern Chinese, Japanese and Korean terms for religion – zongjiao, shūkyō and jonggyo – were all created in the early 20th century by Asian scholars working with Western texts who wanted to translate ‘religion’ from Western languages and needed to invent a word. Their definitions of religion were influenced by Christian religious norms, rather than developing organically from Buddhist, Confucian, Shinto, Daoist or other religious traditions that are more common in those countries, as we noted in our 2023 report, ‘Measuring Religion in China.‘ To this day, the words for ‘religion’ in many East Asian countries and some parts of Southeast Asia refer primarily to organized forms of religion, particularly those with professional clergy and institutional oversight. The Chinese term zongjiao and its Japanese and Korean equivalents do not typically refer to some traditional religious beliefs and practices that are common in these countries. Across East Asia, there are many beliefs (such as in spirits) and practices (such as visiting shrines and making offerings to ancestors) that might be considered religious, broadly speaking. But there is little emphasis in these countries on membership in congregations or denominations, except among Christians and Muslims. These differences might lead Americans of East Asian origin to say they do not identify with any religion or that religion is not very important in their lives, because they do not consider their traditional spiritual practices – or cultural customs that have a spiritual underpinning – to be ‘religious’ in nature.”

The authors of the Pew report also discuss how the broad diffusion of certain beliefs and practices in Asian societies have made it difficult to distinguish between people who are in or out of specific religious groups:

“In many Asian countries, however, religion and religious identity are often understood differently. For example, the practices and beliefs associated with Buddhism, Hinduism, Daoism (or Taoism), Shintoism and Confucianism are often so infused in daily life in Asian countries that even people who do not identify with those religious groups may accept some of their beliefs and engage in some of their rituals. The lines between members and nonmembers, as well as between the religious groups themselves, can be fuzzy.”

Similarly, the authors of the Interfaith America report note that there is “[d]issatisfaction with a label or categorization extended to religious identities.” To illustrate, they share a quotation from one of their interviewees who expresses frustration with trying to classify Asian beliefs, practices, and identities as “religious,” a concept that, in the context of the United States, has largely centered on the needs and worldviews of Christians. “Religiosity … that asks you to identify a religious identity is a very particular and Western concept of religion,” the participant says. “How does America understand what religious identity means and what is valid religious practice?” The authors of the Interfaith American report thus urge Americans to reconsider how they think, talk, and write about religion. “We need to reimagine how to conceptualize and articulate religious identity,” they say. “For many Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, the frameworks and language we use to discuss religious identity in the United States are insufficient.”

Asian Americans as “multiple belongers”

For the authors of both reports, one of the primary reasons why Asian American religious life is misunderstood is the predominant assumption that people have single religious identities. In contrast, their research suggests that Asian Americans are often “multiple belongers” (to use Interfaith America’s term) who have a flexible and capacious approach to religious and spiritual life and practice or belong to more than one religious tradition. As the authors of the Interfaith America report note,

“…[T]here is often an assumption that people have a single religious or spiritual identity — yet many Asian American and Pacific Islanders’ beliefs are multifaceted. One participant, self-described as both Christian and spiritually fluid, belongs to a group that is exploring ‘what it means to reclaim our Indigenous practices’ and asking how to ‘[create] spaces for folks to live into those ancestral practices that we’re still in.’ It can be challenging in the U.S. context to freely express a multiplicity of religious identities, yet doing so appears to play a significant role at the intersection of AAPI race and religion.”

Similarly, the authors of the Pew report are aware of the multifaceted religious life of Asian and Asian American people and intentionally inquire about multiple religious belonging in their study:

“…[S]ome Asian Americans say they feel close to multiple faith traditions. The survey measured these ways of being religious with two questions. The first asked: ‘What is your present religion, if any?’ The second question asked: ‘Aside from religion, do you consider yourself close to any of the following traditions for other reasons (such as your family background or culture)?’ In total, 40% of Asian American adults express a connection to one or more groups that they do not claim as a religious identity. For example, 21% of Asian American adults do not identify religiously as Buddhist but say they feel close to Buddhism ‘aside from religion,’ while 18% do not identify religiously as Christian, yet say they feel close to Christianity aside from religion. And 10% express a similar connection to Confucianism. About two-thirds of religiously unaffiliated Asian Americans (63%) say they are close to at least one of these religious traditions.”

The authors of the Pew study explain that Asian Americans often feel connected to some traditions due to “ancestry or culture.” As they write,

“Many people we talked to, including those who are religiously unaffiliated, expressed a cultural connection to the dominant religious tradition in their country of origin. This sentiment was also apparent in the survey results, which show, for example, that Indian Americans who are religiously unaffiliated say they feel close to Hinduism aside from religion at much higher rates than do religious ‘nones’ of other Asian origin groups.”

At the same time, living in the United States, a predominantly Christian country, appears to have contributed to non-Christian Asian Americans feeling a connection to Christianity. As the Pew authors note,

“For some non-Christians we talked to in these conversations, feeling close to Christianity is an unavoidable result of living in the United States. One Indian American focus group participant who grew up in the U.S. and is not Christian, but who said she considers herself close to Christianity, explained: ‘My whole life I was exposed to Christmas and all this stuff. Even though I don’t believe in it, we had to give gifts … so it was always part of our culture, even though we don’t believe in it.’ In the survey, 34% of religiously unaffiliated U.S. Asian adults (representing 18% of Asian Americans overall) said they feel close to Christianity even though they do not identify as Christians.”

The example of the Indian American individual who feels close to Christianity and celebrates Christmas brings us back to Asian Americans and the winter holidays. As this and other examples reveal, Asian Americans have celebrated Christmas in a variety of ways, and it is but one instance of the broader trends discussed in the Pew and Interfaith American reports: that Asian American religious life contains multitudes, to the point that even using the word “religious” to describe their beliefs and practices doesn’t quite seem suitable.

As the authors of the Interfaith American study recommended, “[W]e should center the wisdom and experience of our AAPI [Asian American and Pacific Islander] friends, colleagues, and interfaith partners as we endeavor to create space for co-existing beliefs, traditions, and practices in the U.S. religious landscape.” I couldn’t agree more. In my view, studying how Asian American religious life is instructive not only for understanding and relating to Asian Americans, but for appreciating and thinking afresh about the religious innovations and imaginations of all people who are crafting creative religious lives, not only at Christmas, but all year round.