A couple weeks ago I saw the classic 1962 Western The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance for the first time. It made me think of grad school. Before you get too concerned, specifically it made me think of a book I read in my twentieth-century history seminar: The Deacons for Defense: Armed Resistance and the Civil Rights Movement.

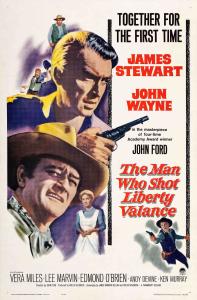

First, some background, in case you too are behind on your consumption of Westerns. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance—intentionally shot in black and white when color was available—is a meditation on the role of the Wild West in the American imagination and the genre of the Western specifically. It juxtaposes two ideals, civilization and frontier, through the two male leads, the powerhouse duo of Jimmy Stewart and John Wayne. Guess which is which.

Jimmy Stewart’s character Ransom Stoddard is a young law graduate headed out West to establish a practice. He literally wants to bring law and order to the Wild West. He encounters a road bump in the form of outlaw Liberty Valance who holds up his stagecoach, robs him of all his money, destroys his law books, and whips him, leaving him for dead. Stoddard is rescued and brought to the small settler town of Shinbone, where he is nursed back to help by an immigrant couple and their available daughter Hallie. Stoddard duly falls for her.

Upon learning that Stoddard is still alive, Liberty Valance wants to fight him, but Stoddard wants to use proper legal channels to bring him to justice. He teaches Hallie, and indeed a large portion of the town, to read. He spends a lot of the movie in an apron because he trades kitchen assistance for room and board until he can establish himself as a lawyer.

Tom Doniphon is the man who rescued Stoddard, and he has also fallen for Hallie. Doniphon is everything Stoddard is not. The town marshal is useless, so the only thing keeping Liberty Valance from completely overrunning the place is Doniphon, an experienced gunslinger and the one thing in town that intimidates Valance. Comparatively bad with words, he says “Pilgrim” a lot and can never quite manage to tell Hallie he loves her. He would not be caught dead in an apron.

For late adopters like me, I won’t spoil the resolution of the plot, but the movie intentionally raises questions around the use of violence. What do you do if you want to follow civilized legal procedures, but the law enforcement in town is incompetent or corrupt? What do you do if violence is used to abridge public discourse intended to change minds? (The Shinbone newspaper printed something unfavorable to Liberty Valance, so he smashed it to smithereens. The newspaper’s (drunk) owner responded, “Is Liberty taking liberties with the liberty of the press?”)

At the same time, it is uncontrolled violence that makes the West “wild” in the film. We learn that years later, when Shinbone developed into a fully civilized town, the incompetent man was no longer the marshal and Doniphon no longer carried a gun.

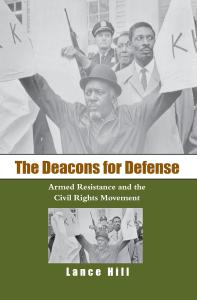

Which brings us to The Deacons for Defense. If you’re like I was when I entered grad school, most of what you have heard about the Civil Rights Movement centers on nonviolent protest against racial segregation and Black voter suppression in the South. This was the philosophical and theological position of its most famous leader, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. If you’re a bit broader in your knowledge of the Civil Rights Movement, perhaps you also know Ella Baker and Fannie Lou Hamer. These women too embraced nonviolent protest as leaders of SNCC—the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

Nonviolence could be either philosophical or pragmatic. It could be embraced as an embodiment of Jesus’s command to love your enemies and turn the other cheek. King and Hamer, for instance, had well-articulated Christian philosophies undergirding their style of activism—Hamer’s despite her limited schooling. Or it could be embraced because it worked: it made your opponents look bad when they attacked you and you didn’t fight back. The nonviolent protest movement was a big tent consisting of both types of participants.

But some civil rights activists did not embrace the philosophy or the pragmatism of nonviolence. The most famous was Nation of Islam member Malcolm X, who remarked that he was “nonviolent with everybody who is nonviolent with us.” In other words, he embraced armed self-defense.

The Deacons for Defense tells the story of a Black group organized for self-defense not associated with the Nation of Islam: The Deacons for Defense and Justice. Organized in Jonesboro, Louisiana in 1964, it soon had chapters throughout the South. The Deacons made it their mission to offer armed protection to movement workers. The book traces how they built on an earlier tradition of protestors who did not always hold the nonviolent line and fought back when provoked. The book argues that it was the combination of nonviolence and violence that led to greater racial justice in the South: Nonviolence called attention to the problem in a way that drew public sympathy. But the threat of racial violence erupting also motivated reform—and protected nonviolent activists.

The Deacons for Defense tells the story of a Black group organized for self-defense not associated with the Nation of Islam: The Deacons for Defense and Justice. Organized in Jonesboro, Louisiana in 1964, it soon had chapters throughout the South. The Deacons made it their mission to offer armed protection to movement workers. The book traces how they built on an earlier tradition of protestors who did not always hold the nonviolent line and fought back when provoked. The book argues that it was the combination of nonviolence and violence that led to greater racial justice in the South: Nonviolence called attention to the problem in a way that drew public sympathy. But the threat of racial violence erupting also motivated reform—and protected nonviolent activists.

The South in the 1950s and 60s was much like Shinbone: in many towns law enforcement refused to act against violations of Black rights and violence against protestors. Famously, in Birmingham, Alabama, Liberty Valance was the marshal: Commissioner of Public Safety Bull Connor unleashed fire hoses and attack dogs on protestors for civil rights. Eventually activists induced a higher legal power—the federal government—to step in to enforce justice.

Should nonviolence be principled or tactical? Is armed self-defense always, sometimes, or never appropriate? In historical fact, different members of the Civil Rights Movement embraced all these stances. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance does not offer a neat resolution to the quandary of the connection between violence, justice, civilization, and the rule of law, and neither will I.