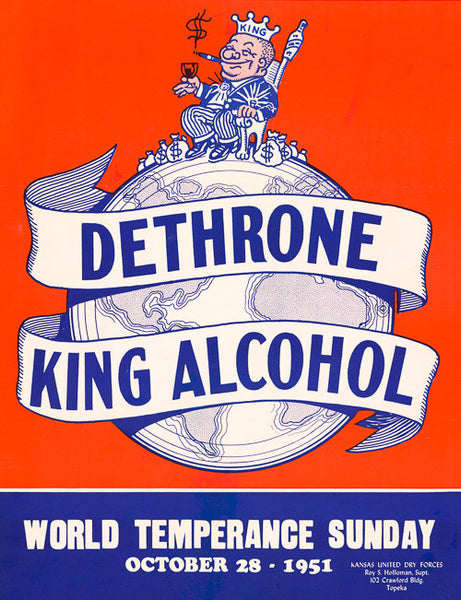

When even the most conservative of American evangelicals started drinking alcohol, they lost their movement’s philosophical foundation for social justice.

That’s an overly simplistic statement, but what I mean by that is that the decades-long evangelical campaign against alcohol – a substance that the Bible does not condemn as inherently sinful – schooled evangelicals in the art of weighing the morality of an action not merely by whether it was intrinsically wrong for an individual but by whether it had a positive or negative effect on society. That’s a socially oriented approach that trained evangelicals in a way to thinking that eventually led them to embrace a variety of other social justice campaigns.

To be sure, when people think today of great evangelical social justice causes of the past two hundred years, the movement to restrict the alcohol industry may not be the first one that comes to mind – precisely because in the view of many people, there’s not much social value in being the killjoy who tries to take away people’s beer, wine, or cocktails.

After all, a significant part of contemporary American evangelicalism is defined more by an enthusiastic endorsement of alcohol than by abstention from it. As one of the many recent indications of this phenomenon, Emma Green’s article about classical education in the New Yorker earlier this month mentioned in passing that one of her sources told her that a “theo bro” is a “conservative Protestant-theology fan who likes to smoke cigars, drink whiskey, talk theology, and has a beard.” And if regularly consuming a potent alcoholic beverage is a defining characteristic of a certain type of conservative evangelical, it’s probably also true of many evangelicals on the more moderate or progressive side. They might strongly detest the TheoBros’ patriarchal attitudes and not really care for their cigars, but when it comes to drinking alcohol, they’re often equally comfortable breaking this old fundamentalist taboo.

Even the Southern Baptist Convention, which for a long time was the largest bastion of anti-alcohol sentiment still left in American evangelicalism, is barely holding the line on its resistance to alcoholic beverages. It hasn’t passed an alcohol-related resolution in 18 years – an unusually long stint for a denomination that for most of the twentieth century averaged one anti-alcohol resolution every two or three years. Its last anti-alcohol resolution (passed in 2006) was hotly contested on the convention floor from messengers who insisted that a blanket opposition to all consumption of alcoholic beverages wasn’t scriptural. And since then, various articles have appeared that suggest that even some of the SBC’s most active and devout members are breaking with the denomination’s official opposition to alcohol.

So, with alcohol consumption enthusiastically celebrated in many Reformed, Anglican, and Lutheran circles – and at least tacitly accepted among a widening group of Protestants from other denominational (or nondenominational) traditions – the longstanding opposition to alcohol among American evangelicals is increasingly confined only to a few small subgroups on the margins of the evangelical movement.

In this context, we may find it easy to write off American evangelicals nearly 200-year campaign against alcohol as an embarrassing, misguided effort to legislate what God’s word didn’t mandate – an example of legalism at its worst, some might say.

But actually, the temperance movement (as the anti-alcohol campaign has generally been known) was a vitally important movement that served as the foundation for many other evangelical social justice campaigns. Most of what American evangelicals learned about social justice was learned through the temperance movement, at least initially. In the 19th century, it was very closely related to the campaign against slavery. Numerous antislavery advocates, including William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass, were also temperance advocates for at least a while. For Garrison, temperance advocacy led him to abolitionism, because he began to see slavery as an even worse social evil than alcohol. And for Douglass, strong antipathy to slavery based on his personal experience led him to also take up the pen against the evils of liquor, because he saw alcohol as a tool that white supremacists used to keep African Americans’ minds enslaved at the same time that their bodies were kept in bondage.

After the Civil War, temperance advocacy was often associated with several other progressive causes, including those related to women’s equality. Frances Willard, a nineteenth-century Methodist who became the Women’s Christian Temperance Union best known president, was an advocate of women’s voting rights and gender equality in pulpit ministry. Marie C. Brehm, a Presbyterian who served as president of the Illinois WCTU, lobbied Congress for the establishment of a Department of Education – an action she took twenty years before the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified and eighty years before the federal government created a Department of Education. If one looks at the religious groups and organizations that supported the temperance movement in the early 20th century, one will see a lot of progressive advocates of the Social Gospel included in the list. It’s no surprise, for instance, that the Christian Century, the leading liberal Protestant magazine of the 20th century, was a supporter of Prohibition for many years.

All of this has been well documented elsewhere in other histories, but what has not yet received much attention is that even in the most conservative denominations that embraced the temperance movement, anti-alcohol advocacy pushed those denominations to show a measure of societal concern that paved the way for other social justice causes. And now that that has been lost, a principal foundation for social justice thinking has eroded as well.

That is because temperance advocacy was based primarily on a social rather than individual concern. Indeed, what may have been the first American denominational resolution on temperance – a resolution adopted by the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the USA in 1811 – was motivated entirely by an observation about the negative social effects of alcohol. The resolution called on the Presbyterian Church to “devise measures, which . . . may have an influence in preventing some of the numerous and threatening mischiefs which are experienced throughout our country by the excessive and intemperate use of spiritous liquor.”

Even when the PCUSA shifted its stance from moderation to total abstinence (as it did in 1877), it continued to be motivated primarily by social concern rather than by a conviction that the individual consumption of alcohol was intrinsically evil. Christians had a duty to abstain “from all forms and fashions which would countenance to any extent the sin of intemperance,” the PCUSA declared. In other words, it was the concern about the societal effects of alcohol use and the potential to contribute to the sin of intemperance in others that led to the position of total abstinence.

This was also true for other late nineteenth-century Christians who took up the temperance denominations. They rarely began their temperance campaigns because of the belief that the Bible condemned all forms of alcohol consumption. Instead, as they looked at the total social effects of alcohol consumption, they concluded that the harm far outweighed the good, and that Christians could love their neighbors more effectively and reduce social evils both by abstaining from alcohol themselves (especially in order to keep others from stumbling) and by curbing the power of the liquor industry.

Indeed, many of the resolutions that the Southern Baptist Convention passed against alcohol in the second half of the 20th century were not primarily about personal consumption of alcohol (which they took for granted that at least the more devout members of their denomination were avoiding) but rather about reducing the negative effects of alcohol consumption in America, such as highway fatality deaths from drunk driving, by curbing the power of the liquor industry. The SBC devoted a lot of attention in the early 1970s to urging the federal government to restrict the advertisement of alcoholic beverages on television, for instance.

Regardless of whether one thinks this was a good use of evangelicals’ time or a misguided one, there’s good evidence to believe that it shaped the way that they thought about a variety of other social issues. When looking at a moral issue, evangelicals who embraced the temperance movement were not merely asking the question, “Does the Bible directly condemn this action?” or “Is this intrinsically wrong?” but rather, “Are the overall societal effects of this beneficial or harmful?”

It was on those grounds that the Southern Baptist Convention passed resolutions against pornography in the 1970s at the same time that it was continuing to pass anti-alcohol resolutions. Its anti-pornography resolution of 1976 was not a resolution urging Christians to avoid looking at pornographic magazines or films (though the denomination would have undoubtedly encouraged Christians not to view pornography); it was instead a socially oriented resolution expressing concern about the “corruption and dehumanizing” societal effect of pornography. Perhaps it was no surprise that this resolution also mentioned the denomination’s concern about alcohol and depicted pornography’s harmful social effects as analogous to the effect of liquor advertising on American society.

The Principles of the Temperance Movement Applied to Gun Control

Today, many American evangelicals have lost touch with this line of argument, and as a result, other social justice causes that made sense to mainstream conservative evangelicals in the 1970s no longer make as much sense to evangelicals in those same traditions today.

For example, it occurred to me as I was looking through some of the SBC resolutions on alcohol in the 1970s that if evangelicals applied the same reasoning to various social issues today as Southern Baptists applied to alcohol a half century ago, the arguments for gun control would probably make a lot more sense to them. As most Christians would acknowledge, it is not intrinsically wrong to own a gun. The Bible doesn’t say anything directly about guns, of course, and even what it says about swords suggests that there are positive uses for them, or at least there have been in the past.

In that sense, we might say that there’s a close analogy between owning a personal weapon and alcohol use; there are plenty of biblical proof-texts that advocates of either could cite in support of their position. But there are also larger biblical principles that some have appealed to in order to caution about the dangers of both personal weapons and personal alcohol consumption. And more than that, one can make the argument that when one looks at the net effect of gun proliferation, one can say – just as temperance advocates said in regard to alcohol – that the harm far outweighs the good.

This, in fact, was the argument that the British evangelical pastor Andrew Wilson made in his debate about gun control with American pastor Bob Thune. In a forum hosted by the Gospel Coalition, Wilson argued that even if the Constitution protected gun rights and even if some biblical verses seemed to allow for the possibility of self-defense, a Christian should support gun control legislation, because the net effect of widespread gun ownership was a greater number of gun deaths. A consistent respect for human life should thus lead Christians to support gun control, because social concern should matter more than one’s own individual rights. This was very closely parallel to the arguments that some American evangelicals in a previous generation had made against alcohol, but Thune seemed unfamiliar with this line of reasoning. Instead of attempting to refute Wilson’s arguments by making the case that increased gun ownership did not lead to a higher number of gun deaths, he merely went through a litany of verses that he said supported a Christian’s right and duty to defend oneself and others through the use of violent force – an approach that completely ignored the negative societal effects of widespread gun ownership, an argument that he seemed to consider irrelevant.

To those steeped in the temperance movement’s arguments, Wilson’s line of reasoning would not have seemed irrelevant – so the fact that it is today is a sign of how far evangelicals have moved from the temperance movement’s reasoning. An American evangelical temperance advocate from fifty years ago might not have necessarily accepted all of Wilson’s claims, but his basic premise – that Christians have a responsibility to restrict things that result in more social harm than good, even when those things are not directly forbidden by the Bible or inherently sinful – would have resonated with them.

And, in fact, in the 1970s arguments for gun control did appeal to some theologically conservative evangelicals who had for decades heard evangelical arguments for alcohol restriction. In 1977, Harold O. J. Brown, a professor at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, argued in his book Death before Birth that when we think about what is necessary to instill in our society an ethic that respects life, laws restricting abortion, alcohol, and handguns are all analogous. “What is at stake is whether society as a whole can tolerate a certain practice – be it the use of alcoholic beverages, abortion on demand, pornography, or handgun possession,” he wrote (Brown, Death before Birth, 77).

The Decline of the Temperance Movement’s Social Ethics in Evangelicalism

By the time that Brown wrote this, a few evangelicals in the movement’s conservative Reformed wing were already beginning to take a dim view of this sort of reasoning. Reformed Christians had once taken a leading role in the temperance movement, but many of them abandoned it by the end of the 1970s, if not before. When the Presbyterian Church in America passed a resolution on alcohol in 1980, it took a very different stance than American Presbyterians had adopted a century earlier, in 1877. Noting that abstinence from alcohol was not required by scripture, the PCA argued that to require a teetotaling stance, as some denominations had, would therefore constitute an unacceptable “binding of the conscience by the commands of men.”

The PCA acknowledged that alcohol abuse was a social problem, but instead of advocating any social or policy approach to the problem, it merely said that the church should “proclaim and embody the reality of the work of the Holy Spirit in the bond of vital fellowship within the body of Christ which is the biblical antidote to the intemperance and escapism of our day.” As best as I can determine, this was probably the last resolution on alcohol ever passed by a PCA General Assembly. And in the view of many evangelicals today (whether members of the PCA or not), that is probably the last word on alcohol that needs to be spoken, because in their view, alcohol is a creation of God and a matter of Christian liberty that no one should forbid. Abuse of alcohol can be addressed through individual regeneration and sanctification, not social policy. The temperance movement was simply wrong, they would say, and the Christian church needs to move on from that past mistake.

But this was not the view of the PCA’s more liberal mainline counterpart, the Presbyterian Church (USA). In 1986, the PCUSA issued an official report titled Alcohol Use and Abuse: The Social and Health Effects that, unlike the PCA resolution from six years earlier, treated alcohol abuse as a social issue and policy matter. Abstinence from alcohol was “encouraged,” but not mandated – yet even for those who chose to drink, the report suggested that alcohol abuse was a significant social problem that the church had a biblical and theological mandate to address. “In our own time Shalom is destroyed in a special way by alcohol use and abuse,” the PCUSA report declared. “This breaking of shalom not only has personal implications of enormous and tragic import for millions of Americans but also results in destruction and cost of catastrophic magnitude to the society. This crisis calls Christians and others to a new level of personal responsibility for Shalom; it also requires more effective public policies to minimize the danger, destruction, and tragedy.”

The report concluded with an exhortation directed to those who might argue that they had individual Christian liberty to consume alcohol. “As faithful stewards of God’s gifts,” the report said, “we must channel and balance personal Christian freedom with an acute and prophetic sense of social understanding and social responsibility to both the Christian community and society at large.”

It was this social responsibility that had given rise to the temperance movement and to so many other evangelical social justice campaigns. But as commitment to the temperance cause has eroded, arguments about limiting personal Christian liberty for the sake of “social responsibility to both the Christian community and society at large” may be eroding as well in evangelicalism.

As a result, we may be left with the contemporary conservative evangelical stereotype of the whiskey-drinking, cigar-smoking “TheoBros,” who know a great deal about theology but are not known for their commitment to limiting their own liberty in order to love their neighbor and seek the good of the community. Perhaps the decline of the temperance cause in evangelicalism affected more than merely attitudes toward alcohol. Perhaps a particular evangelical sense of social responsibility was lost as well.