During Covid, when churches across the country moved their services outside, some might have considered this a novel way to worship. For me, attending Holy Mass or Divine Liturgy under a tent or in a church patio linked me across time and space to the colonial Mexican native peoples I have been studying for two decades, whose sheer numbers necessitated outdoor worship.

I was reminded of this historical moment recently while working on my children’s book, which is set in 1530s Mexico City. I had a lot of time to write last week because my daughter and I spent Spring Break at a cabin in Sonoma County owned by friends at Ignatius Press.

Writing my book as my daughter reads nearby

While there, I wrote a scene where my protagonist, a Nahua reed mat seller named Juan Diego, walks to Mexico-Tenochtitlan (as the Nahuas, i.e. Nahuatl speakers, continue to call it) to speak to fray Juan de Zumárraga, the “priestly-ruler,” the bishop-elect of the newly-formed diocese of Mexico City. Juan Diego passes a small church built from stones taken from the rubble of the nearby Huey Teocalli, or Great Temple, the center of the Mexica (Aztec) universe, which had been destroyed during the final siege of the Mexica-Castilian War in 1521. This little Catholic church stands near the center of Mexico-Tenochtitlan in a section known as la traza española, or the Spanish Layout, a series of streets designed in a grid pattern where Castilians had been living since 1524 encircled by native residences. I have Juan Diego pause in front of this church to cross himself as the friars taught him, but he does not dare to enter, for as a native person, he is not allowed inside; when he does “see Mass,” (a Nahua expression), I have him do so in an open-air chapel in the nearby polity of Santiago Tlatelolco. The irony, of course, is that native workers built the homes in the Spanish traza as well the European church.

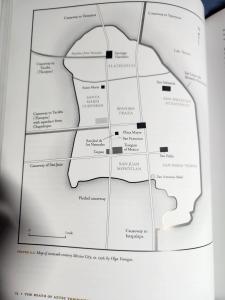

Map of the island upon which Mexico-Tenochtitlan was located, showing the Spanish traza in the sixteenth century. From Barbara E. Mundy’s The Death of Aztec Tenochtitlan, the Life of Mexico City, p. 74

Would colonized Nahuas have been resistant or resentful because they had to build Christian sacred structures? Not really. As the late historian James Lockhart points out in Nahuas After the Conquest: A Social and Cultural History of the Indians of Central Mexico, Sixteenth Through Eighteen Centuries (Stanford U. Press, 1992), local peoples would have enthusiastically constructed these churches because they served as an analogue to the pre-conquest temple and represented communal identity. In indigenous codices, the glyph of a burning temple signaled conquest, so that the (re)building of a sacred structure would, in a way, represent the rebirth of that same polity. I’ve discussed this concept in previous posts: Will the Real Juan Diego Please Stand up? Europeanizing an Indigenous Saint (Dec. 2022), When the Cholulteca Folded onto the Earth: Contested Commemorations of the 1519 Cholula Massacre (Nov. 2022), and in a guest post: The “Histories” of St. Francis in Mexico (Oct. 2021). In addition, as Jonathan Truitt points out in his introduction to Sustaining the Divine in Mexico Tenochtitlan: Nahuas and Catholicism, 1524-1700 (U. of Oklahoma Press, 2018): “[t]he arrival of foreigners did not change [Nahua] understanding of how they engaged with religion, it just changed the religion with which they interacted” (5).

For this post, I will briefly examine the importance of the outdoors for New World evangelization, which officially began 500 years ago this year, in 1524, with the arrival of the so-called Twelve Apostles, a group of Franciscans from Castile led by the saintly Martín de Valencia. In addition to offering Holy Mass in open-air or native chapels, capillas abiertas or capillas de naturales as they were called in the colonial period, early friars used the patios attached to these chapels for catechesis. At the four corners of these patios could often be found posa chapels, or chapels of repose, a New World architectural invention.

One of the earliest examples of outdoor evangelization is fray Pedro de Gante’s Capilla de la Enseñanza [teaching chapel] in Texcoco. A lay Franciscan brother and illegitimate relative of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, Pedro de Gante had arrived to New Spain, unofficially, in 1523 with two companions. He had roman letters carved into the columns outside the chapel so that he could instruct Nahuas, mostly the sons of nobles, in the roman alphabet. Eventually, the friars would develop a written version of Nahuatl, which up to this point was pictographic, and teaching elite boys their letters was the first step.

Fray Pedro de Gante’s Capilla de la Enseñanza in Texcoco with the left and right pillars and their embedded roman letters. Photos taken by the author circa 2007.

The earliest example of outdoor instruction we have in Mexico-Tenochtitlan is a chapel attached to the Franciscan convento of San Francisco el Grande known as the Colegio de San José de Belén de los Naturales [St. Joseph of Bethlehem School for Natives]. After relocating here in 1527, fray Pedro de Gante, now fluent in Nahuatl (indeed, he claimed to have forgotten his native Flemish!), would gather Nahua children in the mornings for instruction in reading, writing, and singing, the latter in Latin. In the afternoons, he taught Christian doctrine, with many of these children becoming regional catechists. Pedro de Gante also taught fine arts and offered workshops in the mechanical arts. Beloved by the Nahuas, they mourned him in the streets when he died.

San Francisco el Grande, the first Franciscan friary/school/garden in Mexico-Tenochtitlan, located in the barrio de San Juan Moyotlan.

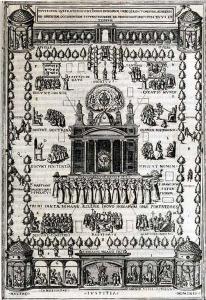

The most famous example of outdoor New World Franciscan evangelization is an engraving of an idealized church atrium in fray Diego de Valadés’s 1579 Rhetorica Christiana, published in Perugia, Italy (the town next to Assisi where Francis was imprisoned). Born in Tlaxcala, New Spain, Valadés was one of Pedro de Gante’s students who traveled throughout Europe and published in Rome and Perugia, writing, among other things, about mnemonic devices for preachers and evangelizers. Rhetorica Christiana was the first book published in Europe by an author born in Mexico.

Idealized atrium in fray Diego de Valadés’s 1579 Rhetorica Christiana

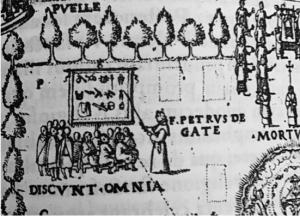

There’s no space to fully analyze this image, so I will simply point out “f. Petrus de Ga[n]te discunt omnia” or fray Pedro de Gante, outside with Nahua students, some of whom stand and some of whom appear to squat (a common indigenous position), discussing everything.

“f. Petrus de Ga[n]te discunt omnia”

When you think back upon those not-so-long-ago days when Covid raged and we felt so isolated from one another, consider how we were, at least during outdoor worship, historically connected to the origins of Christianity in the Americas.