Evangelicals in the States like to have the Reformers and Puritans on their side. However, an undiscerned retrieval of the theology and piety of Reformers and Puritans is ill advised. Wrested from their cultural and historical context, this literature doesn’t hit the same way that it did when it was written. While there is much that might be soberly retrieved for the sake of godly living, caution ought to be exercised.

Pious theology inevitably leads to public theology, and no small amount of pious theology, throughout history, has been crafted with its cultural and political underpinnings in mind. Whether it be the Definition of Chalcedon in the Early Church, the role of the Munus Triplex or the Communion disputes among Protestant Reformers, or the Priesthood of Believers among the Puritans—politics and piety are indelibly entangled. We are creatures of the Word and the sword. We are citizens of two cities, the city of God and city of men. That said, appropriation of the past must be done with care lest retrieval becomes haphazard and sloppy.

I am concerned that too many U. S. Protestants embrace the pious ideas of Reformers and Puritans without giving due consideration to how they will consequently shape their public theology. The public theology of Douglas Wilson, Wayne Grudem, William Wolfe, Ben Sasse and TGC, et al. has not occurred in a vacuous state. While there is a range of consequences and interpretations that may occur, the reality is that it is risky to seek to have the Reformers and Puritans on our side. If our aims are to preserve democracy, then let us not practice undiscerned retrieval.

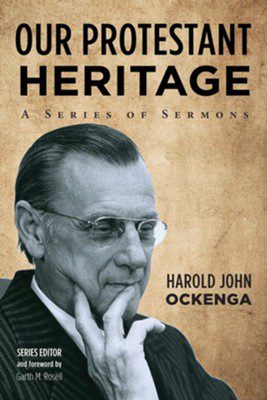

Harold John Ockenga’s Undiscerned Retrieval of Reformers and Puritans

Perhaps the undiscerned retrieval of Harold John Ockenga is worth considering. In the late 1930s, Ockenga felt the rise of Nationalism in the spirit of his age, and he attempted to appropriate the Reformers and Puritans on his side in order to preserve democracy.

Zondervan published an eight-sermon series from Park Street Church of Boston pastor, Harold John Ockenga, in 1938. The series entitled Our Protestant Heritage argued that the political trajectory of Protestantism moved inevitably to dissent, independency, and soul liberty, which were all principles that undergirded healthy democracy. In his preface, Ockenga claimed, “In the proportion that Protestantism dies, the cardinal principles of American Democracy die and we may expect the end of our present government, for America is the product of Protestantism.”[1]

While I am not able to fully address this here, this statement is quite fraught. It already assumes a superiority of Protestantism to Catholicism and it is laden with a deep sense of antipathy towards American Catholics. Considering how Anti-Catholicism has been a perennial failing and feature of Evangelicalism in the U.S., this should come as no surprise. Furthermore, Ockenga’s notion of “America” would be challenged by many of the Latina/o community in the Southwest of the U. S. let alone all those who call themselves Americans, in the broad sense, who live South of the States. Ockenga is only describing a certain kind of America—a White, Male, Protestant dominated breed of America—which had long protected its legacy and supremacy.

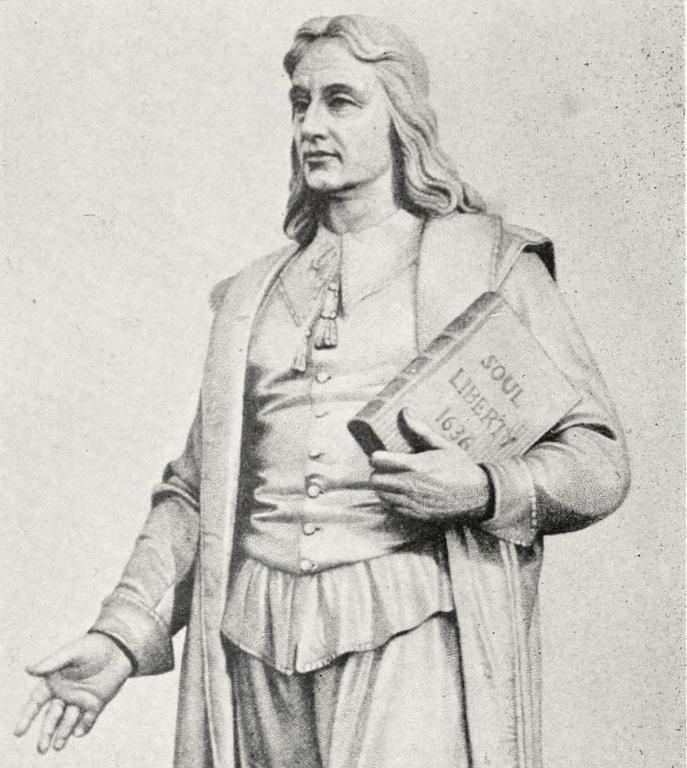

Setting Protestant superiority aside, there are other causes for alarm from the undiscerned retrieval found in this series. The first six sermons are designed and executed with the seventh sermon in mind. Ockenga knew his objective and had to trace a pathway from the superiority of Protestant theology in Germany to its culmination in the political philosophy of Roger Williams in the British Colonies. The first three sermons treat the emerging history of Protestant political philosophy by looking to doctrinal principles from three of the chief ministers of the Protestant Reformation: 1) the reformation truths of Martin Luther in Germany, 2) followed by the Swiss reformer Ulrich Zwingli’s reformed doctrine of communion, and 3) then turns to the predestination doctrine of John Calvin. The second set of three sermons are studies on 1) William of Orange’s employment of Christian Liberty, 2) the power of conscience in the efforts of John Knox of Scotland, and 3) the providence of God in Oliver Cromwell’s England. Overall, Ockenga provides a subtle and seamless narrative from Luther to Williams. Yet, much of it is sophistry that is full of counter-factual historical problems.

Most glaring of which is that Ockenga credits the Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell for the birth of the spirit of independent religion and religious toleration in Britain.[2] This is giving Cromwell far too much credit for a notion that emerges nearer in proximity to the Glorious Revolution when Parliament recognized a mixed-establishment of religion, which included the Church of England, Presbyterianism, and Congregationalism.[3]

If we were to credit any one individual for the merits of toleration, it seems most likely the case that the honor ought to be bestowed on John Locke, who published his Letter Concerning Toleration in 1689, alongside his Two Treatises on Human Government and his Essay Concerning Human Understanding that same year—all as a result of his newfound freedom to safely return to England out of exile in France and back into the patronage of the Earl of Shaftesbury, Anthony Ashley Cooper, who, too, had found himself back into the good graces of England’s new Co-Sovereigns.

However, bestowing this honor upon its rightful heir does not fit conveniently within the golden chain of political developments that Ockenga wished to trace from Martin Luther to Roger Williams. Cromwell fills an essential role as a humble farmer and pious Puritan whose high political aspirations are attained.

As exhibited by Cromwell, in each of these sermons, Ockenga highlights the intersection between the historical subject and that person’s involvement in political and pious affairs. Each sermon demonstrates the argument and claim I’ve already asserted that pious theology is entangled with public theology. Those that produce the former are inevitably implicated in the latter. This is not a claim that needs to be refuted, nor is it a problem that must be undone. This is simply the way of being, thinking, and living in the world. Our identity, rationale, and practice is one of a body/soul composite that has political and spiritual consequences. The problem isn’t that we are political and spiritual creatures. The problem lies in the kind of political and spiritual creatures we become and how we become those creatures. Since we become what we consume, undiscerned retrieval of past political and spiritual creatures might reproduce problems from the past.

Harold John Ockenga’s Fear of Christian Nationalism

The motive for Ockenga’s program of retrieving the Reformers and Puritans to be on the side of democracy becomes apparent in sermon seven on Roger Williams. The anxiety that underlies the whole sermon series is the rise of Christian Nationalism in the U. S., the phenomena of which Ockenga indicates parallels the rise of nationalism in other places, such as Germany. After arguing for Williams’ view of soul liberty, the idea that individuals should have freedom from compulsory and State enforced religious belief, Ockenga asks whether this principle is endangered today.

He goes on to quote a statement from Dr. Samuel M. Shoemaker, the American leader of the Oxford Group Movement, which concludes with an endorsement that the State be empowered to control the Church. “We really want the state to take the responsibility for keeping things in order, so that we may continue our religious practice as we wish.” Ockenga then pairs Shoemaker’s comments with Frank Buchman’s “praise of Hitler as the Savior of Europe.” Ockenga then appeals to the response of “a brilliant religious editor” whom he quotes at length:

What does this mean? Only one thing, if it is logically carried out, namely, the rule of the churches and of religion by the state, and that is precisely what is being attempted in Germany, in Spain, in Mexico, and in Russia. To give the state authority to decide what is good religion and what constitutes a good church is to throw civilization back in benighted monarchism, which is what we have as a matter of fact in present day dictatorships.

Ockenga goes on to make his own comments on the situation of the U. S.:

A few years ago such state control of religions was on the wane, but now voices in favor of it are rising on every hand. At the close of the last century the greatest amount of tolerance that the world has seen existed, but today it is being repudiated. Liberalism today is on the wane. Soul liberty is greatly in danger. Roger Williams’ thesis, ‘Live and Let Live,’ is being rapidly discarded.[4]

While it is admirable that Ockenga went to such lengths to defend democracy from the rise of Christian Nationalism, he failed to do so in a prudent way. If you carefully read the prior six sermons, you encounter logical fallacy after fallacy that indicate that having the Reformers and Puritans on your side is not the look Ockenga really wants. For some, such as Ockenga, it seems de rigueur to have the Reformers and the Puritans on your side, whether it’s the first half of the twentieth century or the first half of the twenty-first century. But let me show you how problematic undiscerned retrieval really is by turning to the notable interpretation of an expert interpreter of Roger Williams and an outstanding, careful, detailed historian of religion in America, Edwin Gaustad.

Edwin Gaustad on Williams

Roger Williams was one among several early Bostonians who created diasporic communities of dissent from the Boston politic they contested. As John Winthrop consolidated his power from 1636–38, in short order various men peeled off Boston to settle other areas. These men’s departure from Boston were either prompted by exile or ambition. Thomas Hooker and Samuel Stone were among the first. They set out in 1636 to found Hartford. From this Hartford settlement, came the earliest democratic constitution in the world, The Fundamental Orders. Prior to its ratification, Thomas Hooker famously preached, “The foundation of authority is laid in the free consent of the people…As God has given us liberty let us take it.” Anne Hutchinson’s brother-in-law, John Wheelwright, departed in November of 1637 after his fast-day sermon led to an ecclesiastical trial that concluded with his exile to Hampton, New Hampshire and ultimately Maine. Next in the Boston exodus were John Davenport and Theophilus Eaton, who departed in 1638, on their own initiative, to settle the New Haven colony.

Why did these people depart from Boston? Gaustad indicates that the Bostonian leaders, under the propitious power of John Winthrop, had simply recreated the same political dilemma that existed in Britain. Rather than the political corruption deriving from the Stuart monarchy, the same corrupting impulses emerged from among the Church Elders and General Assembly Counsel Members, nearly all of which, if not all, had dual appointments in both spheres. Even when others peeled away from Boston, the Bostonian Counsel repeatedly attempted to over-reach their ecclesial and political power by interfering and intervening in the affairs of these other fledgling colonies. Simply reading some of the letters and overtures of Boston ambassadors to Rhode Island reported in David Hall’s documentary history of the Hutchinsonian Controversy substantiates this over-reach.[5]

The story of the first to depart from Boston, Roger Williams, has its own intriguing backstory that demonstrates this over-reach. Williams and his wife Mary left England aboard the Lyon in late 1630 and arrived in Boston in February, 1631. He was eagerly welcomed as “a godly minister” by Governor Winthrop and offered to be Boston’s minister. Noting the Boston governor’s and charter members’ commitments to the Crown and Church of England, Williams determined they were not separatist enough for his tastes. Roger summarily turned down the offer, and he and Mary headed to Salem. After a stint in Salem, the couple journeyed to the decidedly religious separatist Plymouth, where they settled until 1633. Williams’ reputation for “radicalism” got him in trouble in Plymouth and so he returned to Salem. However, Boston could not simply leave him be in Salem. In Salem he tussled with John Cotton, Boston’s minister, over women being veiled during prayer, and he was implicated in an episode where Salem’s John Endecott came under fire from Boston for desecrating the British National flag; the papal cross had been cut from the flag. Roger Williams’ resistance to the status quo persisted when he protested to Natives being deprived of their land without due compensation.[6]

The breaking point that led to exile was when Williams criticized the Massachusetts policy that all male inhabitants, under the age of 16, must swear an oath of allegiance to the colony and Crown, concluding with “so help me God.” Williams’ protest to this policy ostentatiously concerned his views of religious tolerance and freedom and subtly displayed his views on freedom of speech and conduct. Suppose someone did not believe in God. Imposing such an oath upon a person would cause him to speak against his conscience. Williams had not long before been appointed to pastoral duties in Salem, elevating the status of his opinions and providing a public platform for his ideas.

Boston officials, seeing the imminent danger to the status quo, brought him to court in Boston in July, 1635. This action encroached on affairs in Salem and breached what Williams thought was charitable and respectable behavior between government and church. As a result, Williams sent a letter to the “Elders of the Church at Boston,” indicating his belief that this should be handled in the sphere of the church. Doing so would leave open the possibility that the Boston church might respect the independency of the Salem church’s practices, preventing political over-reach of Boston into Salem and ensuring the independency and autonomy that might have its locus within the churches. By October, the Salem church had become split in its views and Boston government officials decidedly took action, summoning Williams to court on October 8. Williams was given a final day to recant. Returning to court on October 9 of the same mind the court so ordered “that the said Mr. Williams shall depart out of this jurisdiction within six weeks.”[7]

Ad Fontes, Bypassing the Danger of Undiscerned Retrieval

Gaustad’s interpretation of the Williams events demonstrates how out of sync and radical Williams’ ideas, as well as the Plymouth separatists, were from Magisterial Reformers like Martin Luther and Thomas Cranmer; Republican-minded reformers like Ulrich Zwingli, John Calvin, and John Knox; or pious political figureheads like William of Orange or Oliver Cromwell. All of the aforesaid did not have such a radical notion of separation of Church and State. Rather, all of these figures, in their given place and time, to one degree or another, permitted much permeation and convergence between the State and the Church relation, and they were all quite rigorous proponents of a Church established by the State. Roger Williams’ perspective was quite radical at the time and the consequences of it would not be articulated with clarity until Isaac Backus became sharpened, as iron sharpens iron, by his publication war interlocutor, Joseph Fish, in the 1760s and 70s.[8]

It’s altogether too simplistic to argue for a streamlined evolution of political thought from one individual to another, such as Ockenga attempted. The geo-political context of each of these people contributed unique features. While some borrowing and exchange took place, we have to compartmentalize the advancements of each of these figures and hold the body of literature they produced and represented within their own contexts.

I have a fond appreciation of the Reformers, the Puritans, and the Neo-Evangelicals. My library is filled with primary and secondary works on all these subjects of history, which I’ve cursorily discussed here. This is not a takedown of Reformed, Puritan, and Neo-Evangelical thought. It is a critical re-assessment that suggests we should employ discernment and deep study on these subjects before cherry-picking, ransacking their writings, or weaponizing them for our own ends. I propose that people today can prevent undiscerned retrieval by taking seriously the notion of ad fontes.

Rather than receiving an interpretive history handed down from generation to generation, we should go “to the sources” themselves and re-evaluate them. The legacy of our interpretive history alone existed in a context itself that slanted in some direction, and we ought to be weary of that slant. Before we appropriate Great Thinkers and Great Books, for the purpose of enlisting them to be on our side, we should first read these people and works and study their historical and social context in depth. Doing so will prevent undiscerned retrieval and foster a studied and rich appreciation of the past.

Furthermore, we might be saved from naïve or ignorant employment of their ideas to support our own arguments. We might then see how indelibly linked their pious reflections were to their public theology and also perceive how those in our own day have been shaped by the undiscerned retrieval of Great Thinkers and Great Books they have consumed, such that, it seemingly has led them to appropriate the same tyranny, of which Revolutionary patriots and Early Republic citizens were so weary, the tyranny of a State regulated Church, which today is known as Christian Nationalism.

[1] Harold John Ockenga, Our Protestant Heritage (Eugene: Wipf and Stock/Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1938), vi.

[2] Ockenga, Our Protestant Heritage, 101, 104–05.

[3] On the mixed-establishment of religion in the British Empire, see Katherine Carté, Religion and the American Revolution: An Imperial History(Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2021).

[4] Ockenga, Our Protestant Heritage, 120–21.

[5] David Hall ed., The Antinomian Controversy, 1636–1638: A Documentary History (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1968).

[6] Edwin Gaustad, Roger Williams (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 6–9.

[7] Gaustad, Roger Williams, 10–13.

[8] Joseph Fish, The Church of Christ a Firm and Durable House (New London, 1767); Isaac Backus, A Fish Caught in His Own Net (Boston, 1768); Joseph Fish, The Examiner Examined (New London, 1771); Isaac Backus, An Appeal to the Public for Religious Liberty (Boston, 1773); Isaac Backus, The Nature and Necessity of an Internal Call to Preach the Gospel (Boston, 1792).