by Janine Giordano Drake

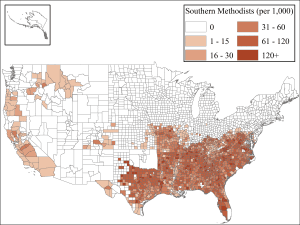

When Woodrow Wilson ran for president in 1912, he called himself a “Christian.” The man was a Southern Presbyterian aristocrat, accustomed to a world where wealthy churchgoers had to own expensive suits, dresses, and hats, as well as pay an annual pew rent, in order to attend church regularly. By 1890, the date of the map below, Southern Presbyterians represented some of the wealthiest, most well-connected people in every county in the South. Some Presbyterians contributed to their “Home Missions” committees at the local and national levels, even supporting “extension” missions in a few places. But, poor people were generally not welcome in churches of the wealthy. As I’ve written elsewhere, membership in a Presbyterian church signaled membership in an intentionally exclusive club.

I’m not sure Wilson would have called himself anything more than a “Presbyterian” before the turn of century. Socialists and other reformers used the term “Christian” to refer to their hopes of reforming the nation in the interests of the common good. Charles Sheldon’s In His Steps and Laurence Gronlund’s Cooperative Commonwealth got Americans talking about big questions like, “What does it mean to follow Jesus?” and “How do we design a Christian society?” In the Gilded Age North, to use the term “Christian” was to push the conversation toward ideals that did not quite exist on the ground. Edward Bellamy liked the term. Meanwhile, church leaders were fighting over minutiae. Presbyterians and Methodists were still fighting over predestination. Baptists sand Methodists were still fighting over the correct way to perform baptisms. Holiness -Pentecostal revivalists traveled circuits and held regular summer revivals which celebrated prophecy and the gifts of the spirit. Wealthy brick-and-mortar churchgoers would sometimes agree to disagree about predestination, but many did not even acknowledge these revivals as “Christian” worship experiences. When organizations used the term Christian–like the Women’s Christian Temperance Union or the Young Men’s (and Women’s) Christian Association–they made an aspirational statement about the possibility of overcoming denominational divisions in the interest of the common good. For some, these were radical ideas.

But in 1912 and again in 1916, Woodrow Wilson was determined to appropriate the term “Christian” for the Democratic Party. A Christian, as he defined it in his “New Freedom” campaign platform, was “more concerned about human rights than about property rights.” Wilson hoped that if he worked closely with the Federal Council of Churches’ and branded himself an acolyte of the Social Gospel, he could convince Northern evangelicals to break with the party of Big Business to support a particular reformation of industrial practices. He worked to earn the respect of the American Federation of Labor and went on to support the rights of collective bargaining during the first World War. Wilson worked hard to make the tenets of the 1908 Social Creed of the Churches–the principle that child labor was wrong and workers should be paid “as much as industry can afford”–into the foundation of the Democratic Party platform. He wanted this to be so because he thought it would be winning strategy. And it was.

As I wrote about in my book, The Gospel of Church, Wilson’s definition of “a Christian” was also intended as a cudgel against the many more radical definitions of the term “Christian” in the early twentieth century. Wilson had little respect for Christian pacifists, for Christian Socialists, for Christian anarchists, for Christian integrationists–not to mention Roman Catholics or Black nationalists. He worked with the Federal Council of Churches to make the term “Christian” equate to “respectable” white Protestants and their modest ideas for social change, label that implicitly labeled as “non-Christian” all those whose goals for social reform did not coincide with his own. Wilson’s Democratic Party appropriated and gentrified the ecumenical movement.

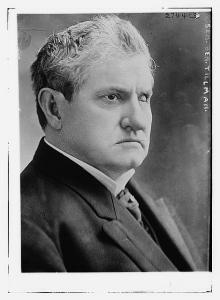

You might also say that Wilson’s “Christianity” did little more than put Ben Tillman’s violent, white supremacist Christianity of Gilded Age South Carolina into more refined clothing. Pitchfork Ben, as he was called, was rather open about the fact that he had every intention of disfranchising African Americans from voting and protecting and defending the “white republic” from “pollution” by “unfit” peoples. Pitchfork Ben had no problem with white vigilante violence on Black bodies, a phenomenon that pervaded his home state while he presided as governor. In 1899, Pitchfork Ben defended the principle of the White Man’s Burden on the floor of Congress (even as he acknowledged that the American execution of those goals was rather poor). Tillman used the concept of a “Christian” as a dog whistle for the “protection” of white power. When Wilson appropriated the term in his bid to make the Democratic Party popular in the North, he only slightly amended the substance of Ben Tillman’s Christianity. Moreover, to the extent he updated it, he also made sure to define it to put down what he understood as the urban revolts of the North (the prospect of socialism) as well.

This is not the first time that a major presidential election will be used as an excuse for politicians to redefine the term “Christian” to fit their political agenda. One might even argue that when denominations are weak and take the majority of their funding from the wealthy, political parties play this role more than any other stakeholder. Woodrow Wilson won two presidential elections because he convinced Americans that his definition of a Christian was the right one. But he did not have to do that much work—he did not have to articulate the racism and classism and nationalism in his terms–because that work was already done for him by the previous generation of Democrats. Wilson was no theologian and knew little of the prophetic tradition of Christianity. He was not even sure that Roman Catholics were Christians. But Wilson confirmed many Americans’ cultural projection of what a Christian looked like–he carried on the white nationalist tradition of his forefathers–and that was all he had to do to win a presidential election. His predecessors and allies did most of the work for him.