by Janine Giordano Drake

Last November, I had the chance to visit the National Archives on Pennsylvania Avenue. From the special guest list at the entrance to the secret cafeteria in the basement to the giant shelf of old census data, there was not a detail in that building that I did not find thrilling. But perhaps the most fascinating experience of all occurred after a librarian handed me the giant hand-written record book which kept track of all the “free” land Congress gave away, starting in the 1860s. Hours bled into days as I read through every entry in that book, puzzling through the decisions made in each and every allocation. The book fascinated me as a historian, but it moved me on another level as well. The book read to me as a giant balance sheet of federal assets, but without any accounting for liabilities. The cost of this land, not to mention the responsibilities of the people who got this land, were not mentioned a single time in this giant book.

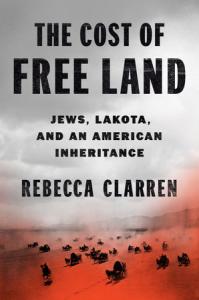

When I recently read Rebecca Clarren’s new book, The Cost of Free Land: Jews, Lakota, and an American Inheritance (Penguin House, 2023), I was happy to find a conversation partner on the moral consequences of homesteading. Clarren’s book is a side-by-side microhistory of two communities in South Dakota from the late nineteenth century to the present: the Lakota people, and the Jewish refugees who settled on this “free land” as homesteaders. The story of the Lakota people is a story of dispossession, enforced boarding schools, broken treaties, resource deprivation, disease, and neglect by the federal government. It especially emphasizes the tragedy of the Dawes Allotment Act, a law which broke up tribal lands into family parcels and invited settler families opportunities to “homestead” on unceded tribal land which ought to have been reserved for future generations of Lakota.

Meanwhile, the story of the Jewish refugees who came to “Jew Flats” is a story of rags to riches white prosperity. Clarren traces the story of the Moskowitz family escaping European pogroms to settle on the very cold Northern frontier in the late nineteenth century. The Moscowitz family uses this homestead like the little boy in Shel Silverstein’s The Giving Tree uses his tree. When one use of the land runs dry, they are already on their way to find another. When farming becomes less profitable, they run general stores. When alcohol becomes more valuable, they sell perfumes and cosmetics (legal alcohol) and participate in bootlegging on the side. When they get caught for bootlegging, oil is discovered under their old family lands, and they lease the land to oil companies. The Moscowitz family is hard-working and resourceful, and has little direct interaction with their Lakota neighbors. But, in Clarren’s telling of the story, her family’s failure to reckon with the cost of their “free land” is a theft for which they ought to make restitution.

In the act of doing research for the book, Clarren, a journalist from Seattle, participated in a study on ancient Jewish rituals of restitution and apology. She learned that this ritual was not that different from traditional Lakota understandings of repair. According to Maimonides’ Law of Repentance, Clarren writes, one who finds themselves guilty of injustice can follow the following six steps to make restitution. I quote her here in full:

“First: Stop doing the harm. Second: Confess as specifically as possible what harm you have caused, and, ideally, say this truth out loud in public. Third: Begin the work of transforming yourself from a person capable of causing such harm to one who isn’t. In ancient days, people changed their names. Today, it might mean therapy.) Fourth: Make financial restitution that reflects the size of the harm. Fifth: Apologize in a way that doesn’t necessarily anticipate being forgiven but that makes clear to the victim that you have heard them, and that you understand how you have caused them pain. Finally: When you face the opportunity to cause the same sort of harm, make different choices” (pp. 228-229).

In a way, Clarren’s whole book is an act of making this apology and imagining a way forward with different choices. She also makes a substantial financial act of restitution. I found the book both thought-provoking and moving. What is the cost of this “free land” which enabled so many of our settler ancestors to purchase property and gain the sense of satisfaction that they supported themselves? What do we owe the people whose land was stolen so that we might use it? Are you responsible for a theft if you find yourself in possession of stolen property? While Clarren’s book is about a little sliver of North Dakota, the questions she raises can be asked about any settler family living on any sliver of the United States. As a work of history, of religion, of accounting, I recommend the book very highly. I look forward to engaging the growing bodies of scholarship that follow up on these questions.