Around the year 200, Bishop Palut was an important leader of the church in Syria. Unless you study the church history of that region, there is no reason why you would or should have heard of him, nor of the weird-sounding sect of the “Palutians” that is mentioned in the mid-fourth century. But as I will argue, that Palutian name is actually critical for how we write Christian history in any time and place, right up to the modern day. The Palutians, you see, are us.

In the first Christian centuries, Syria and Mesopotamia were booming centers of Christianity, but virtually all those local forms of the faith were suspect in the eyes of later orthodoxy. There were (broadly) Gnostic believers like the followers of Bardaisan; there were Marcionites, who rejected the Old Testament and the God it preached; and there were Jewish-Christian baptismal sects. There were also believers who were none of the above, and who followed the orthodoxy taught by what we would think of as retroactively as the “mainstream” churches of Rome or Antioch. These orthodox or catholic believers were a small minority, so much so that the other Christians of the region dismissed them as following the “sect” of Palut. They were called Palutians, and it was not a compliment. Logically too that same demeaning term would apply to every other Christian before or since, who happened to be neither a Gnostic or Marcionite. It would apply to every Catholic, Protestant or Orthodox believer who accepted such weird ideas as accepting the Old Testament as well as the New.

We know the term from an angry denunciation written by the great Syriac Father Ephrem of Edessa, who complained about the label in a letter that used several puns on the Palut name, and its p-l-t root:

Their hands have let go [plt] of everything. There are no handles to grasp. They even called us Palutians, but we have spewed [plt] them out and cast away [the name]. May there be a curse on those who are called by the name of Palut, and not by the name of Christ. . . . Palut too did not want men to be called by his name. If he were alive he would curse with all curses, for he was the disciple of the Apostle [Paul] who suffered pain and bitterness over the Corinthians when they abandoned the name of the Messiah and were called by the names of men.

Ephraim was protesting that people like himself weren’t Palutians, a term that suggests a cranky sect, they were orthodox! So why did those enemies not recognize that fact? The answer is that they were doing what most Christians have always done when dismissing critics or rivals. You give them a name, ideally that of a specific person, and you pretend that they are a sect. Whenever we read or write Christian history, then consciously or otherwise we follow the same practice. We write about how THE CHURCH (imagined in such upper-case terms) confronts the various troubling -isms and -ists and -ites and -ians. Depending on the era, they are Valentinians and Sabellians and Arians and Nestorians and Novatians and Priscillianists and Wycliffites and Hussites…. Oh dear, why could all those -ists and -ites and -ians not just realize that they were heretics, schismatics, and sectarians, so foolishly cut off from the true church?

Of course, most of those -ists and -ites and -ians would think of themselves as “orthodox” or “Christians” or “faithful believers.”

Why does this labeling happen? It’s obvious enough.

First, when you label enemies in that way, you suggest that they their ideas stem wholly or chiefly from an individual, a human being who is necessarily flawed, and who is presumably urging those principles to promote his (usually his) interests and his vanity. Equally of necessity, he cannot be a team player, one who acknowledges the wise consensus of the church throughout the ages. You do not believe these things because you have thought them through, but because you have fallen under the spell of a heretical leader. And in the early centuries, that idea of a “spell” was taken very literally, often in a demonic sense.

Attributing those ideas to an individual also means that they cannot have any deeper roots, any historical authenticity. In the case of the Palutians, we can see this is absurd because we know (or believe) that our own Christian orthodoxies were not all cooked up by one ambitious deviant around 200AD. But surely we should apply a similar tolerance to understanding other ideas that are conventionally termed heretical, and wonder whether they too might represent opinions that were once widespread and accepted.

As a tendency, this goes back to almost the origins of the Christian faith. Even in the Book of Revelation, in the 90s AD, the church at Ephesus is praised for rejecting the evil teachings of the Νικολαϊτῶν, the Nicolaites, presumably followers of some Nicolas (the church at Pergamos was more favorable to them). I wonder what those mysterious Nicolaite believers thought of the author of Revelation, and what kind of dreadful -ism they attributed to him?

Oh, did you see me commit this same sin that I am presently denouncing at the beginning of this column? I spoke of “Marcionites,” which is the term applied by the victorious church that defeated that rival tendency. Marcionites just called themselves “Christians.” I should properly have said “so-called Marcionites.”

The best instance of this labeling process is perhaps Arius, who is generally and misleadingly thought of as the founder of the Arian heresy around the year 310. In reality, most of Arius’s ideas had been very standard among the most venerated church Fathers over the previous century or two, including Tertullian and Origen. Alexandre Dumas famously wrote that “The difference between treason and patriotism is only a matter of dates,” and very much the same thing can be said of heresy and orthodoxy. Adam Renberg did an excellent summary at this site on the theme of “Is Arianism Real? On Name-Calling and Othering in the Church.” It deserves to be widely read.

When Arius was successfully labeled as “Arian,” then the associated ideas seemed to stem from his personal whims and evil tendencies, and Arius became the sinister model that the later church used to frame all later heretical thinkers – and I use the term “framed” advisedly. Many modern scholars would refuse even to call Arius an “Arian” in any later sense of the term, which was so escalated and distorted in successive polemics. Nor, by the same standards, was Nestorius a Nestorian.

Clarence Darrow famously observed that “Every advantage in the world goes with power.” In historical writing, one vital aspect of that power is the ability to determine the language used for respective sides in a controversy, to decide who gets labeled as the dissident, the breakaway, the sectarian, as opposed to the normal and faithful. To use a sectarian label, such as Arian or Sabellian or Nestorian, automatically implies that the opposite position must be that of the One True Church, which stands far above the indignity of needing any such sectarian label. Even to use the label has hopelessly prejudged the issue, and conceded the sectarian quality of the supposed dissidence – even when in fact the dissidence represents an older orthodoxy. Exactly the same is true of the concept of “Gnostic” or “Gnosticism.”

As an ancient joke declares: Ah, you and I are both doing the Lord’s work! You in your way, I in His.

You will note that sects and schisms never ever triumph, because when they do, they cease being regarded as sects and schisms, and they become too powerful to cross or criticize. They also acquire power to label their own rivals as -isms and -ists. If it prosper, none dare call it heresy. The best example of this is probably the fringe Jewish sect originally known as the Jesus Movement.

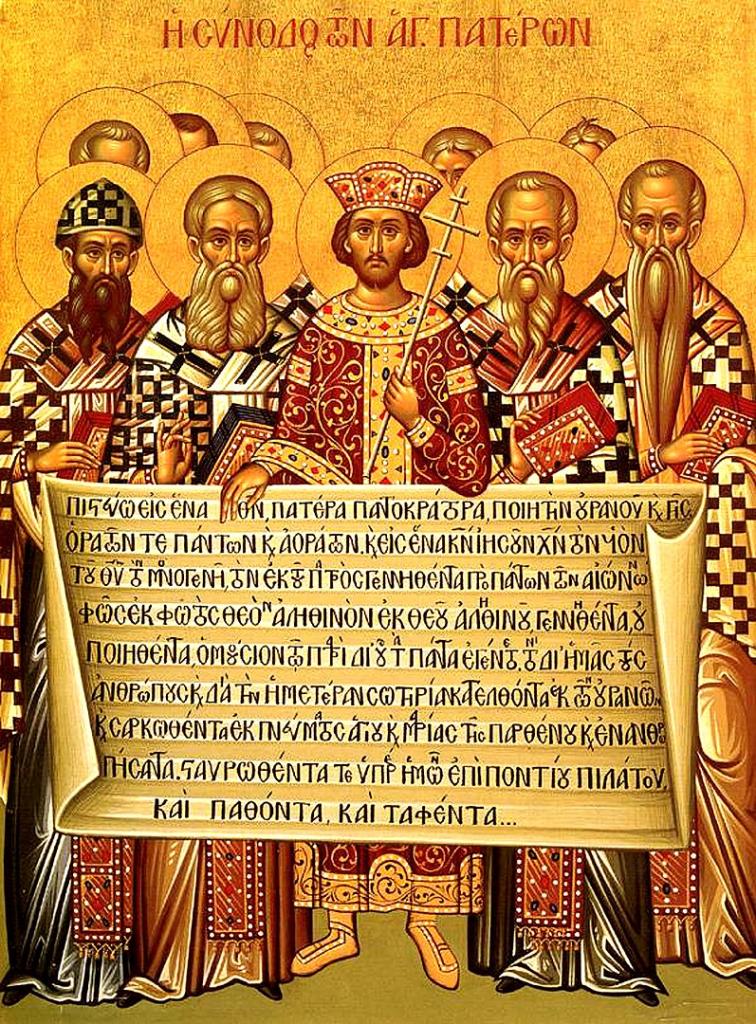

This all affects what we know (or what we think we know) about the history of particular movements, and about Christian history as a whole. When a particular position was defeated, that had immediate consequences in terms of the systematic and near-total destruction of documents that expressed its views. When the Council of Nicea condemned Arius in 325, not only were his writings to be destroyed, but anyone refusing to hand over such texts faced the death penalty. In consequence, we have lost most of the writings of Arius and his allies and supporters, and his precise views are just not recoverable. Yet modern scholars insist on narrating such controversies as if they can somehow provide any kind of balance. To take another example, later generations remembered and cherished the Cappadocian Fathers of the fourth century as warriors for orthodoxy, whose brilliant rhetorical skills had driven the Arians to defeat. We would have a much better chance of scoring the two sides in their respective bouts if later church authorities had not destroyed virtually all of the documents from the Arian side, leaving the Cappadocians to win retroactively by default.

So we know nothing about what a given heresy actually believed? No matter! When they wrote the history of heresy X, partisan scholars and heresiologists inevitably described it through the stereotypical characteristics already formulated against the earlier movements A, B, C, D…. This links to a rhetorical tactic by which some new school of thought is being stigmatized as being more or less overtly a subset of some previous heresy that everyone thinks is horrible. Inevitably, all heresies start to look alike. That tendency encourages scholars, even in modern times, to think that they can write about common themes in heresies, or in heretical leaders. In fact, all those movements had in common was that they lost.

Imagine a world in which what we call the heresies won, and our “orthodoxy” was today remembered only as the eccentric teaching of the Palutians, ideas concocted by the ungodly Palut around 200 AD, in violation of the authentic traditions of the faith promulgated by Marcion and Bardaisan. Scholars might try to discuss these historical battles as fairly as possible, but once you have started accepting pejorative labels like “Palutian,” the battle is over. Just why could those Palutians not have realized they were a sect inspired by the vain ambitions of one man? Why were they so stubborn, so deluded?

In summary, when you read church history, always remember that those -ites and -ists and -ians might well have ended up being judged very differently, and more positively.

Maybe we are all Palutians. Or it would help us to remember that someone once thought we were.