I have been writing and thinking a lot about evangelicalism, the myth of evangelical consensus, and Mark Noll lately. (Hi Mark! We’ve never met, but you seem very nice!)

Most recently, I reviewed, again, The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind for ByFaith, the magazine of the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA). An original draft is printed below. Let me know what you think!

….

Admittedly, it’s a little odd to be reviewing a book that is thirty years old. But historian Mark Noll’s The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind, remains both pressing and prescient. He’s probably not happy about it.

Noll, an accomplished scholar and long-time professor at Wheaton, Notre Dame, and now Regent College, is an evangelical himself. The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind, then, was his “epistle from a wounded lover,” his “cri de couer.” In the preface, he describes the tension this caused him as a scholar and a committed Reformed Christian. “The thought has occurred to me regularly, that, at least in the United States, it is simply impossible to be, with integrity, both evangelical and intellectual.”

But Noll refused to give either up. And, of course, he’s right. Our faith can inform the deepest of questions and most cerebral of studies. “When we study something, we are of course learning about that thing,” Noll asserts, but even more we are “learning about the One that made that thing.” Evangelicals, he maintains, should push forward into science, the humanities, social sciences, political philosophy, with boldness and curiosity. This expansive faith, what twenty years ago might have been called a Christian worldview, should draw believers into wonder, into study in all sorts of academic disciplines, and ultimately into worship. Actually, Noll asserts, “to neglect…serious attention to the mind, nature, society, the arts–all spheres created by God and sustained for his own glory—may be, in fact, sinful.” (23) After all, as Jesus explained, we are to “love the Lord [our] God with all [our] heart and with all [our] soul and with all [our] mind.” (Matthew 22:37, emphasis mine).

This is certainly what I was taught at my Christ-centered college preparatory school. I studied European History and statistics and William Faulkner as well as Bible and apologetics. There was no contradiction. “All truth is God’s truth,” we were told repeatedly, encouraged to cultivate a “passion for learning.” It was this passion, this holy, fearless curiosity, that led me to graduate school and, ultimately, the professoriate. Still, my scholarly vocation and my belief in the gospel feel mutually sustaining.

So, why have modern American evangelicals historically been so averse to intellectual pursuits? Why, as Noll puts it, has there been a “failure to exercise the mind for Christ”? Why the huddling in fear?

Noll looks to the past. In elucidating how “the scandal came to pass,” he offers a sweeping history of Protestantism, finding a “rich heritage of fruitful intellectual labor,” from Luther to Calvin to Jonathan Edwards to John Winthrop, until the twentieth century. At this point, feeling besieged by theological modernism and cultural change, evangelicals opted to play defense. If the world was going to reject the supernatural fundamentals of the faith, they would simply “no longer pay attention to the world.” (123) They also adopted a simplistic, dogmatic literalism and dispensationalism, positing certainty and alienating dissenters. But their defense of supernatural truths of the faith (some of which, Noll admits, are important), meant that when they confronted the intellectual, theological, and cultural challenges of modernity “the cupboard was nearly bare.” (106) Even after the “intellectual disaster of Fundamentalism,” evangelicalism never recovered. Instead, Noll argues, evangelicalism held on to reductionist Biblicism and hysterical eschatology, with dire consequences for both politics and science. Which brings us to the present.

Noll wrote Scandal of the Evangelical Mind in 1994 with hope for intellectual renewal but also skepticism that evangelicalism could ever contribute to the life of the mind. “The recent past,” he admitted, “seems to point in no other direction.”(239) Again, Noll was right. And he is likely dismayed at how right. Modern American evangelicalism has doubled down on anti-intellectualism. And, unlike our historical forebears, this willful ignorance is not in service of any piety, but self-righteous anger and blind partisanship. Our “worst features” have remained our “methodological keystones,” leaving evangelicals woefully ill-equipped to face the pressing challenges of our day–economic inequality, technological change, globalization, climate change—susceptible to conspiratorial thinking, and lacking a winsome public witness.

There is some good news, though. And critiques of Scandal of the Evangelical Mind point the way, inviting big questions. First, the book has rightly been criticized for its exclusion of women as well as Black evangelicals. For instance, to the pressing question “Did American democracy have a place for one if one was Black?” Noll answers, “evangelicals gave little thought to the matter.” (74) Of course, Black evangelicals certainly did. Mary Beth Mathews’s Doctrine and Race and Daniel Bare’s Black Fundamentalists highlight examples of Black Christians who held evangelical theologies and devoted substantial intellectual effort to questions of racial justice. Why isn’t Dr. King, one of America’s great intellectual theologians, considered in the analysis? Isaac Sharp, in The Other Evangelicals, has shown how not only Black evangelicals, but feminist, liberal, and gay evangelicals were edged out, narrowing the story Noll tells. Another critique has to do with Noll’s geographical timeline. In his rendering, “evangelicals” in the Protestant Reformation, Scottish Enlightenment, American Revolution, and Early Republic made great intellectual contributions, only to be “hopelessly disfigured” by Fundamentalism. But, as historians–including Mark Noll!– well know, evangelicals made intellectual arguments for all kinds of nefarious enterprises, including slavery. Antebellum Southern evangelicals were evangelicals, too, invoking their Biblicism, their activism, to the cause of violence and plunder.

So what’s the good news here?

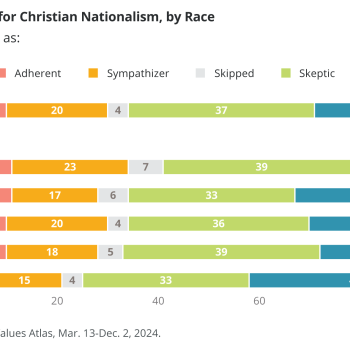

Matthew Sutton recently published an already field-defining essay, “Redefining the History and the Historiography on American Evangelicalism in the Era of the Religious Right.” In it, he traces the rise of a cadre of prominent religious historians, including Mark Noll, who developed an evangelical consensus school. These scholars, resisting what they saw a reactionary and anti-intellectual trends in the new Religious Right, created a more palatable “usable history,” first “retroactively” defining evangelicalism in broad and abstract terms, and then creating an unbroken lineage of both orthodoxy and orthopraxy throughout American history. This interpretation became very popular with historians and laypeople alike and remains so. But there is no “no multi-century evangelical throughline” at least not without a definition “so elastic you could stretch it to eternity,” and to invent one is to “decouple the movement from politics, race, class, gender and sexuality,” that is to say, historical and cultural realities. Modern evangelicalism, Sutton claims, is best understood less as the most recent iteration of a timeless theological lineage and more as a “religio-political coalition.” The term itself was adopted by a group of white Fundamentalists in the 1940s who were looking to rebrand and create an “effective political lobby,” one that would “represent the interests of socially and politically conservative Christians.” Sutton concludes, then, that modern American evangelicalism is best defined as “a white, patriarchal, nationalist, religious movement made up of Christians who seek power to transform American culture through conservative learning politics and free-market economics.”

Understanding evangelicalism this way helps make sense of the scandal of the evangelical mind and of the insistent anti-intellectualism that marks our current moment. It helps makes sense of the unreflective biblicism, the patriarchal heresies, the nationalist curriculum rewrites, the demonization of educators and professors and universities, of the slander and exclusion of evangelical scholars who transgress the cultural and political allegiances of evangelicalism—from Dr. Kristen Kobes du Mez to Dr. Jemar Tisby to Dr. Francis Collins to Dr. Tim Keller. Mark Noll seems to agree. See, while those who might theologically qualify as evangelical Christians can be found on both sides of the political aisle, doing science and writing history and theology, the lines of exclusion fall on purely political, reactionary grounds. In a new 2022 afterword to Scandal, Mark Noll admitted, “the word ‘evangelical’ is now next to worthless for serious investigation of questions about Christian faith and scholarship.”

It’s probably time to give up hope on the evangelical mind. Either its time has passed, or it’s been compromised in service to slavery and its afterlives, or it never really existed at all. But the good news is: we do not need to give up hope for the Christian mind. One that is not warped by partisan politics or degraded by seeking power. One that can hold wonder and mystery, that is humble and open, fixed on Jesus, and being renewed day by day.

When I walk into my classroom at a public, secular university, this is what I bring with me. There remains, for me, a truly sacred joy in collectively wondering about the past, in asking big questions about perspective and causality, in watching young people awaken to the world of ideas. In 1994, Mark Noll asked evangelicals not to “scorn the good gifts of a loving God.” That remains a good admonition–if we have ears to hear.