My present research involves the relationship between religion and American empire. Recently, I have been viewing that through the context of the idea of “vastness” that dominates current work on early American history, namely the urge to go beyond traditional frontiers, whether national, racial, or chronological. As I’ll show today, a geographical perspective brings those various themes together nicely, and actually has quite a bit to say about the foundations of quite diverse US religious traditions.

American history has been shaped at least as much by its modes of transportation as by its political parties, and the successive worlds created by the sailing ship, the Conestoga wagon, the steamboat, the train, and the automobile differed from each other quite as much as the eras so often described by merely political labels. As Thoreau wrote of America’s great cities in the 1850s, “Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Charleston, New Orleans and the rest are the names of wharves projecting into the sea (surrounded by the shops and dwellings of the merchants), good places to take in and to discharge a cargo.” Forty years later another observer might well have described the cities of that era as chiefly rail depots. Those successive patterns shaped the geography of American religion and, as I will suggest, even its native theologies. I’ll concentrate here on Catholics and Mormons, but the same points apply much more widely.

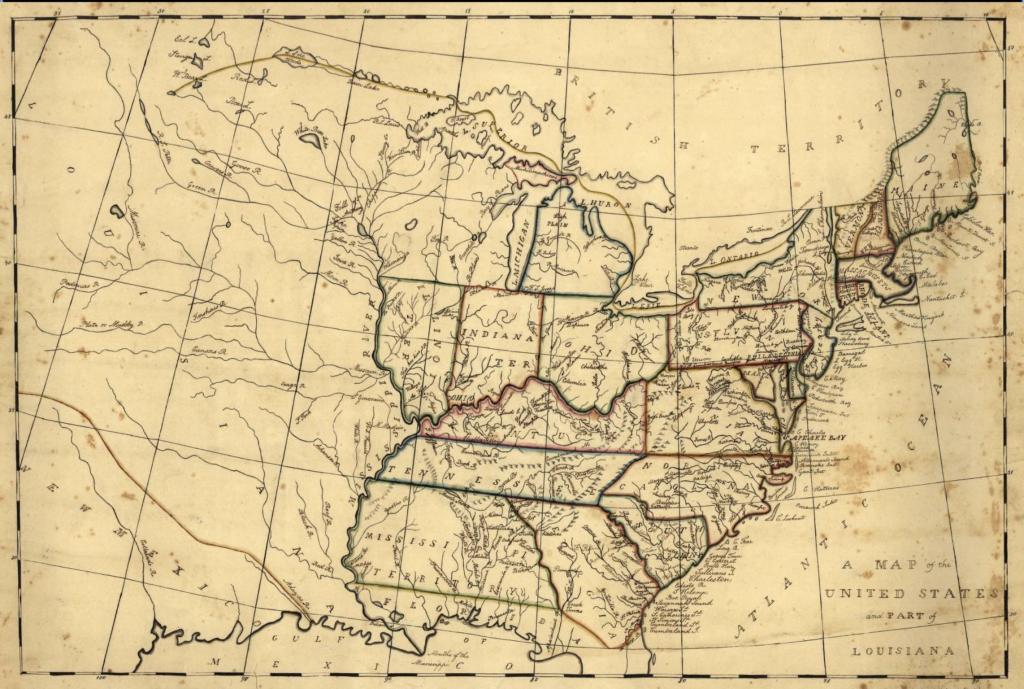

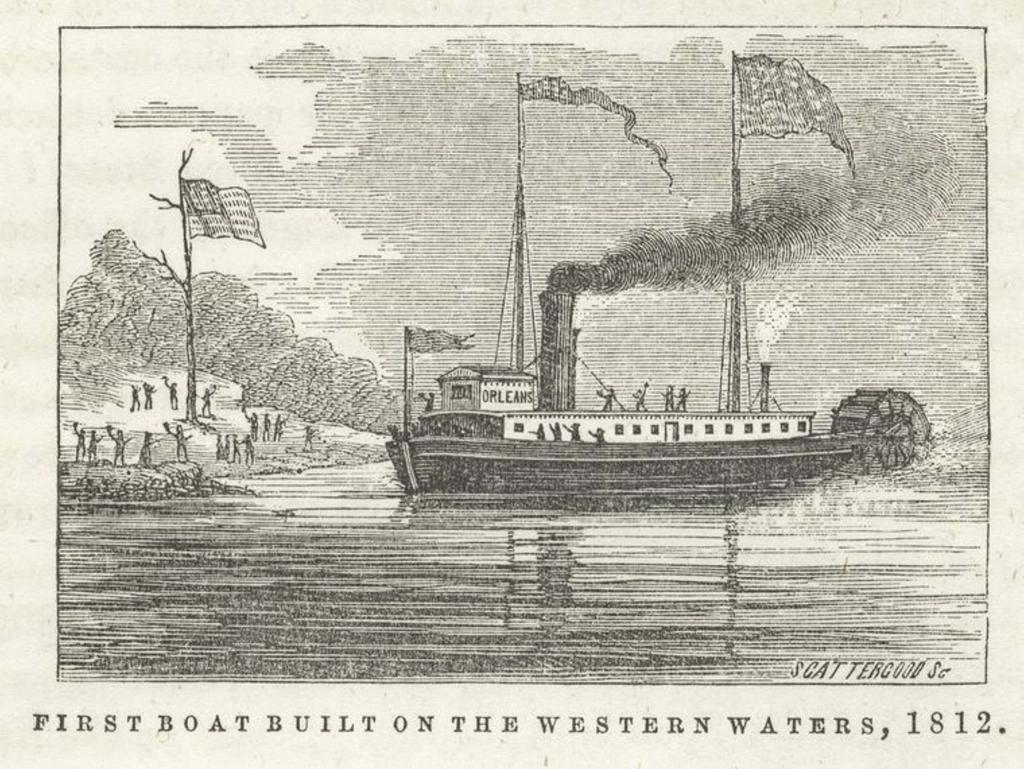

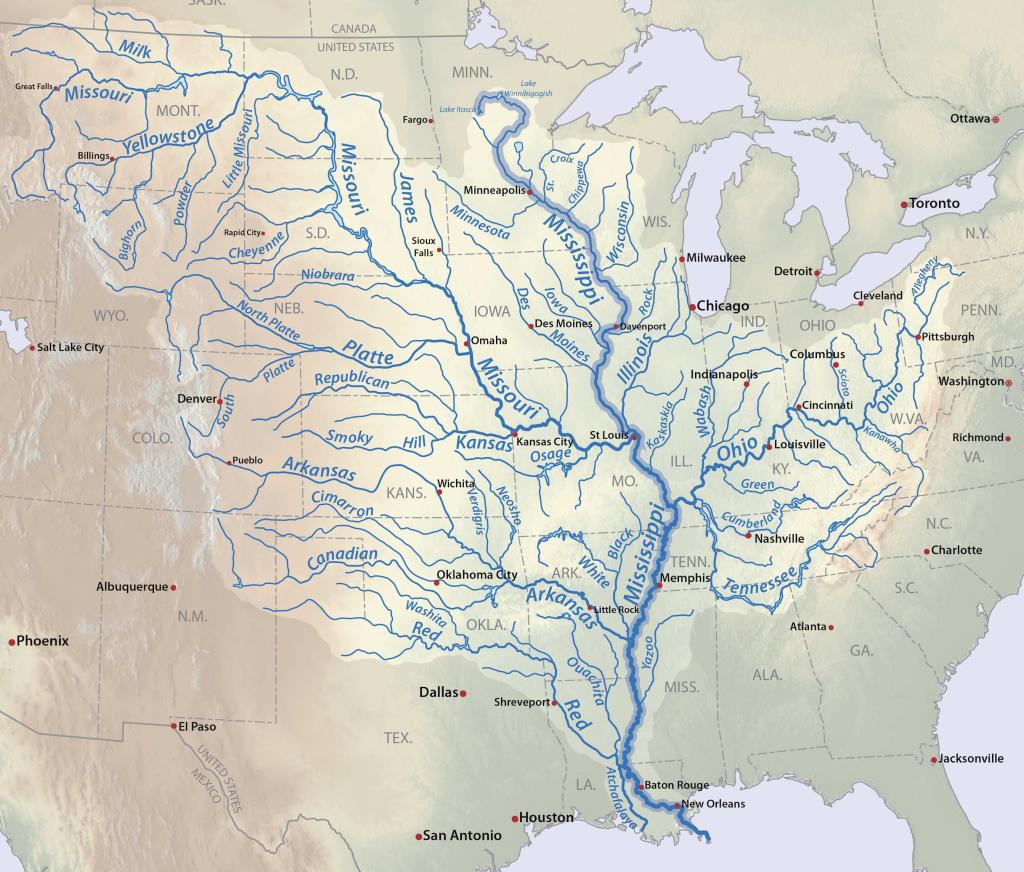

Let me focus here on the age of rivers, which were so critical to founding the American continental empire that became the Lower Forty Eight states. Before the Revolution, the British colonies clung tightly to the east coast, and one major factor in provoking independence was the British desire to restrain Americans from plunging into the heartland, where travel depended utterly on the great rivers. After independence was achieved, rivers were the critical thoroughfares of the growing continental empire. New technologies contributed, and above all steamboats. After several false starts, the continuous history of American steamboats begins with Robert Fulton’s efforts with the Clermont in 1807. By 1811, river steamboats were leaving Pittsburgh to sail down the Ohio River to the Mississippi and on to New Orleans.

You get a sense of just how important these routes were when you see the negotiations to end the War of 1812, and some of the key points at issue. At a point in 1814 where the British thought they were definitely winning, they drew up their own vision for the future of the continent, in which the US would have no naval forces on the Great Lakes, and the British would have navigation rights on the Mississippi. The continental future was built on water.

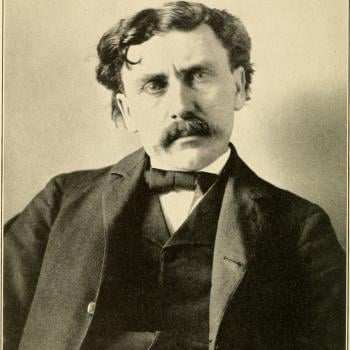

Here is Lyman Beecher, in Cincinnati in 1835, describing the astonishing impact that these routes had on everyday life and people’s horizons:

When I first entered the West, its vastness overpowered me with the impression of its uncontrollable greatness in which all human effort must be lost. But [then] I perceived the active intercourse between the great cities, like the rapid circulation of a giant’s blood; and heard merchants speak of just stepping up to Pittsburgh — only 600 miles — and back in a few days ; and others just from New Orleans, or St Louis, or the Far West; and others going thither; and when I heard my ministerial brethren negotiating exchanges in the near neighborhood — only 100 miles up or down the river — and going and returning on Saturday and Monday, and without trespassing on the Sabbath.

By 1850, a list of the largest US cities contains few surprises. The list is headed by New York/Brooklyn, followed by Boston, Philadelphia, and Baltimore. But racing up behind them, and jostling for the fifth position, were Cincinnati and New Orleans, both intimately tied to the river routes, and St. Louis was not far behind.

To observe the consequences, look at the history of the country’s Catholic dioceses. Baltimore was the first in 1789, and in 1808, four new dioceses followed. This actually makes a great trivia question: what were they? Well, Boston, Philadelphia and New York are easy enough, and then – um, Bardstown, Kentucky. Bardstown? The church was not imagining a Catholic megalopolis at that site, but rather thinking of the obvious future directions of settlement, above all along the Ohio, and its tributaries, the Tennessee, the Cumberland and the Wabash. The Bardstown diocese covered what would ultimately become ten US states.

Over the next forty years, Catholic dioceses and archdioceses grew rapidly, from those five to over thirty, and throughout, we can map the expansion mainly in terms of river routes, to the Mississippi and beyond. We also discern the ghost of the older French empire that had been held together by these water routes. Many of the first bishops were French by origin and nationality.

If we look at the foundations by 1840, a few are on or near the coast – Charleston, Richmond, and Mobile – but overwhelmingly, this is a river story. Key names include Cincinnati, St Louis, Vincennes, Nashville, Natchez, and Dubuque. Except for Cincinnati, all of these were older French foundations, as was Mobile. The see of Detroit (1833) shows the new interest in the Great Lakes following the building of the Erie Canal (although Detroit was also a French foundation). In 1841, the Bardstown diocese was moved to Louisville. The one year of 1843 brought new dioceses in Chicago, Little Rock, Milwaukee, Pittsburgh, as well as Hartford. Throughout, the map shows that continuing western core of dioceses at Bardstown/Louisville, Vincennes, and Cincinnati. That is a pure lake-and-river geography, and it is a near perfect map of the patterns of White settlement and the building of political empire.

As the hierarchy developed, the church created new metropolitan sees, with Archbishops. Here is another trivia question: Baltimore was the first such see in the US, obviously enough, but what was the second? It is unguessable: Oregon City, 1846, the precursor of Portland. By 1850, the US had four more metropolitan sees, namely New York, New Orleans, Cincinnati, and St. Louis. St. Louis was “the Rome of the West.” That is also a full generation before Boston, which did not gain metropolitan status until 1875.

I should say that this list does not include some distinct French and Spanish diocesan foundations: New Orleans in 1793, and the Diocese of California in 1840.

Source information can be found here

That is the Catholic story, but it is of far wider application. Look at any evangelical revival of the era and ask why it happened where it did, and why it had the impact it did. How did people travel there, and by what means did they move further into the continent, carrying those new ideas and inspirations? This again is a river story. The oldest US Jewish congregation west of the Alleghenies, is of course in Cincinnati (1824). Where else? New Orleans followed in 1828.

Of course, rivers themselves don’t inspire theologies… well, maybe they do.

As Americans ventured along the Ohio, the Tennessee, and the Mississippi, everywhere they saw the remains of the great Native cultures that had built all those mounds and earthworks, and who themselves had so closely followed the rivers throughout: such were the Hopewell cultures, and the later Mississippian. Follow the rivers and you eventually come to the great mound cities, with their temples. Put that map of ancient remains together, and it looks so much like American settlement in that era, and the later structure of the American Catholic hierarchy. The Cahokia mound complex stands only a few miles east of St. Louis.

US expansion into the Ohio country produced countless reports of the discovery of quite vast remains from the ancient mound-builder cultures, including geometric earthworks, road systems and giant carved figures – many of which were recorded, but are now lost. One of the most astonishing such complexes, at Newark, Ohio, became a White settlement in 1802. The following year, when Ohio gained statehood, the first state capital was actually at Chillicothe, the setting for still more mound remains. The Serpent Mound was first mapped in 1815. Then Americans pushed west to the Mississippi, and by 1818, steamboats were sailing from St. Louis.

Was the new American empire being built over the remains of a glorious predecessor, another empire far more ancient than the French?

Quite a few travelers were struck by the contrast between the radical technological modernity represented by the steamboats and the archaic lost world of the mounds. Here is Charles Dickens en route to Cincinnati in 1842:

Through such a scene as this, the unwieldy machine takes its hoarse, sullen way: venting, at every revolution of the paddles, a loud high-pressure blast; enough, one would think, to waken up the host of Indians who lie buried in a great mound yonder: so old, that mighty oaks and other forest trees have struck their roots into its earth; and so high, that it is a hill, even among the hills that Nature planted round it. The very river, as though it shared one’s feelings of compassion for the extinct tribes who lived so pleasantly here, in their blessed ignorance of white existence, hundreds of years ago, steals out of its way to ripple near this mound: and there are few places where the Ohio sparkles more brightly than in the Big Grave Creek.

Accounts of ancient mounds circulated through newspapers, prints, and of course travelers’ tales. Nobody could doubt that America had been home to ancient settlements and even substantial cities, and most people believed that mere Indians could not have constructed them (as of course they had, and as Dickens knew). It just remained to discover which set of unknown immigrants had done the deed. Were the mound-builders the Lost Tribes of Israel? Phoenicians? What exactly? And what happened to them? Surely they must have been wiped out by savage Indians. Hmm, not just one ancient race, but two in competition, and one survived to become Indians.

The Lost Tribe theory found expression in the View of the Hebrews, published by Ethan Smith in 1823, a work that has massive and unavoidable parallels with the Book of Mormon that Joseph Smith first published in 1830. In the Mormon scheme, the sinful Lamanites destroyed the noble Nephites, and devolved into the Indians of our familiar experience. Although later Mormon attempts to prove the historicity of that work focus on Central America, Smith left no doubt that he was visualizing the world of the North American mounds. How could it be otherwise? Smith’s world, and so much of the world of early Mormonism, was utterly conditioned by rivers and river transport: just think of Nauvoo, Independence, and Carthage.

In 1834, Smith was traveling across western Illinois when, at Griggsville near the Illinois river, he passed the mound burial of one he identified as Zelph, a “white Lamanite” of the Ancient Book of Mormon era. (Griggsville is a hundred miles north of Cahokia, and a hundred miles south of the later Nauvoo). To borrow the famous line by the writer Saki, Romance at short notice was Joseph Smith’s specialty. The following day, Smith wrote that

The whole of our journey, in the midst of so large a company of social honest and sincere men, wandering over the plains of the Nephites, [my emphasis] recounting occasionally the history of the Book of Mormon, roving over the mounds of that once beloved people of the Lord, picking up their skulls and their bones, as a proof of its divine authenticity, and gazing upon a country the fertility, the splendor and the goodness so indescribable, all serves to pass away time unnoticed.

This was by no means the only attempt in that era to appropriate the mounds for that Mormon schema.

If you want to see a precise map of Nephite and Lamanite America, as imagined by Joseph Smith, then you can find one easily by looking at this helpful map of moundbuilder remains. These are the Plains of the Nephites, and their lost cities.

Follow the rivers and you map the religious life of early and early national America