We love a nice round number—and 250 years since the U.S. War of Independence began is too significant to pass up. Somehow in fifty years of living on the East Coast, I haven’t toured Philadelphia’s historical sites, and doing so this year seemed appropriate. While at the Museum of the American Revolution, a well-organized museum and very accessible—highly recommend!—I was struck with what an opportunity this celebration is for us to join together across the culture wars and political divide. As I sat in one of the theaters being introduced to the meaning of the ideals of the Revolution and how they had affected the world, I could see that the audience was made up of folks from many different walks of life, and yet we were all finding the country’s origin story inspiring.

What we do with this origin story matters. We need founding myths. The way we begin impacts how we go on. Recently I read the classic American Scripture for the first time. Pauline Maier’s analysis of how the Declaration of Independence has been used over time and the comparison of it with the Hebrew and Christian Bibles rang true to me. As Christians take texts that were forged in historical time and place for particular reasons and apply them to their own day and age, the Declaration has become something more than a historic artifact of colonial communication to the wider world. This is especially interesting, because the Declaration is not a governing document, and yet it arguably is more significant and memorable to folks in the US today than our actual Constitution.

Maier traced the history of the colonists taking the decision for independence and self government to mean more than merely self-rule. They wanted to do something new—and in this way it wasn’t some sort of “genius author” who made the Declaration an inspired piece of political philosophy, but the ordinary people themselves who engaged with it at the time and who decided to act to create the United States. These citizens did not all agree on exactly how that new polity would be, but the ideas in the Declaration were flexible enough to be claimed by the range of priorities within the colonies.

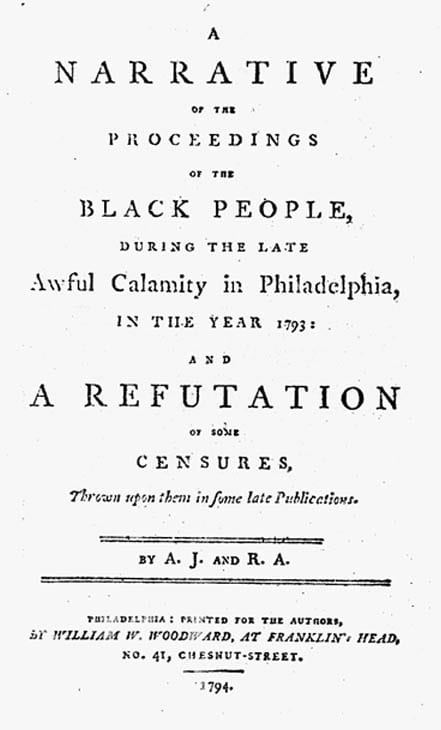

However, the Declaration’s power to motivate lay dormant, according to Maier, until Abraham Lincoln began the tradition of using the Declaration to support and communicate advocacy for expanding civil rights and citizenship. In this way, its use evolved “to become the moral standard by which we live as a nation.” Successive groups read its words as arguing for more inclusion or for critiques of the current polity. As with the Christian Bible, it had prophetic value both for inspiration and as a cudgel for ordinary folks to use in their political life. And it is in its continuing use by everyday folks that the Declaration remains a guiding light to citizens in this country—and around the world.

It’s possible that as a historian, my practice of analyzing nation-state formation in the generic, and my critiques of nationalism have dulled my ability to be inspired by the genuinely courageous and unique actions of those thousands of folks in the thirteen colonies 250 years ago. Listening to the presentations at the Museum of the American Revolution, and the lively stories of the elderly guide who led the walking tour my husband and I took, I allowed myself to be genuinely moved. Regardless of the motivations of political leaders at the time, people of all stripes decided to take the ideals of equality and liberty and make them their own. And they continued to do so, with all the hard work it entailed, for the next 250 years.

For instance, the men writing the founding documents did not intend for women to be fully included. And yet women saw themselves as part of this endeavor, participating in the fighting, engaging in the political debates, fundraising and advocating for partisan ideas about how to form the new country, and even voting when and as they could. The Museum of the American Revolution does precisely what Maier is describing through its exhibit “When Women Lost the Vote” and through its historical interpreters engaging with the public.

This summer, public historian Emma Cross was in residence at the Museum to tell the stories of the women camp followers in both armies during the Revolutionary War. Cross portrayed particular women who believed these political developments and ideas mattered to them and who gave their health and time and skills to be part of them. The Ladies Association of Revolutionary America also had members at the Museum, engaging in tangible ways with the public to demonstrate how women were impacted by the war and how they made its goals their own. As my husband and I toured the museum, we found ourselves thinking in new ways about the movement for independence and the creation of a new country based on new ideals because of the widening of the stories being told.

Similar efforts are made at the Museum and at national history sites all over the US to include women, African Americans, Native Americans, immigrants, folks with disabilities, religious communities, and the working class. When I talk to park historians or interpreters they all say they want their sites to be welcoming to and inspiring to wider audiences—they want them to be more than “dad history.” Our walking tour guide spent most of his time emphasizing how many of the people who signed the Declaration or who worked in Philadelphia for the nation’s formation were in debt or had close family in debtors’ prison. The economic element of the Revolution and what it meant for the poor were close to his heart. I learned new facets of the story and I’m his way of telling it allowed some people to see themselves in the story in a way they might not have before.

At a time when there is plenty to critique about our nation’s politics or the goals of various political groups, I found myself grateful to the public history folks who are working so hard to inspire disparate groups with the vision for what those early ideas could and did do. We need scholarship that complicates the past and is about more than hero worship. But we also need stories that remind us of the heroism of ordinary folks and that encourage us to apply the words, ideas, and motivations of the past to our world. Those applications will probably look very different from what the founding generation thought—women voting!??—but that’s the genius the Declaration of Independence. It’s what we make of it. Happy Birthday, USA. Let’s make it a good one, and let’s try to be a better version of ourselves this year.