It’s Lent: Let’s Go to the Wilderness

Budget cuts in the US government have resulted in more folks paying attention to the National Parks recently. While arguments over which branches of government are more or less vital or efficient, my own conversations seem to reveal that the National Parks have bipartisan support. The importance of having swaths of land preserved from development and preserved for citizens to enjoy holds wide appeal. It seems a truism that we need wilderness areas to fully experience the breadth of what it means to be human.

There’s a history to this interest in wilderness spaces as sites of enrichment, health and beauty. It wasn’t always this way. In Wastelands: A History Vittoria Di Palma describes the fear and sometimes loathing with which many societies viewed what we now consider to be an unadulterated good. In the English-speaking world, “wilderness” comes into our vocabulary via the King James Bible, and can just as easily describe a desert as a sheep pasture or a region on the edges of human habitation. Di Palma depicts the Western Christian view of nature as one where humans were cast out of Eden and reclaiming the wilderness is part of the process of the regeneration of sinful people. Mountains, forests and swamps were viewed with fear and even disgust.

Encounter the Sublime

Modernity changed so much of this for Western Europeans and then much of the world often called “Western. The development of scientific categorization and exploration allowed people to feel more in mastery of the natural world. The Industrial Revolution caused nostalgia for the connection to the natural world that was lost with increasing mechanization and urbanization. Wild spaces became imagined as places where humanity could encounter the sublime, rather than as dangerous, monstrous, or unproductive.

If, as Di Palma argues, we have invented the idea of wilderness, I think it is most often imagined as a place where human actions are less clearly visible (though all of the earth is impacted by human activity). And if we feel a need for it more acutely in the modern world, it is because we need moments where we are reminded of our Creatureliness. Modernity is demarcated by commitments to progress and efficiency and productivity and to the expansion of energy and mechanisms to do this that humans have invented. We are the sovereigns and creators in this world. Wilderness, for us today, involves spaces that have few if any reminders of the marks humans make through their own ingenuity. They are places where we can’t ignore that we are part of the creatures of the world and dependent on the plant life and land that God made.

Open to Awe

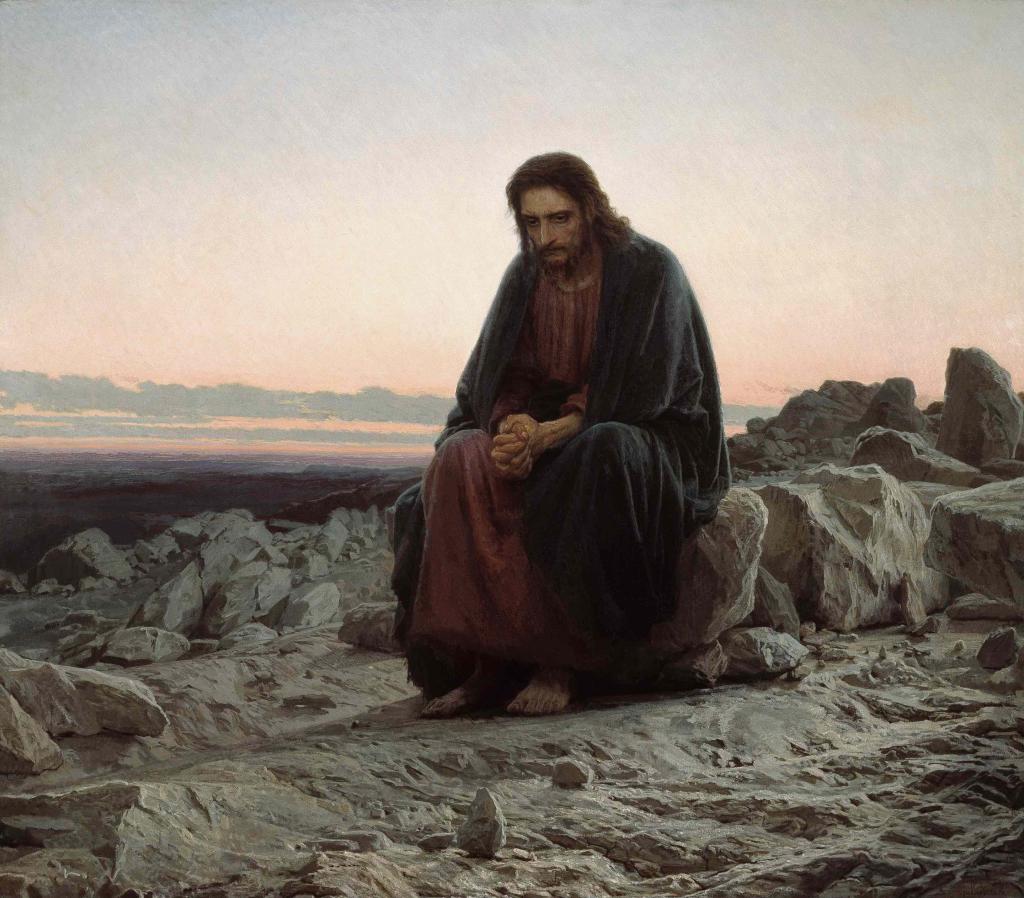

Perhaps this is why we still find ourselves looking to wilderness spaces to find God. Our lives are so crowded here in our technicalized world that we rarely can confront our mutual dependence with Creation. We need to be in places where we have less control and so are more open to awe, to the confrontation with the sublime, and therefore to the presence of God.

In the Bible, people are always finding God in the wilderness or desert or wastelands. They sometimes go to those places to escape danger or because they need refuge and rest. Or they go because they are being punished. Perhaps they want to find inspiration or the Spirit. Wildernesses can often be places to start over. They are almost always alone (with the exception of the Israelites wandering in the wilderness). In any case the confrontation with God, the comfort of God, the New Creation that God makes does doesn’t happen without the starkness and the loneliness of this sort of wilderness experience.

The Christian Season of Lent

Perhaps our desire for these wild places and the God who shows up there can be something we practice during the Christian season of Lent. Choosing to fast, to withdraw in some way from the productions of humans and to rely on the generosity of God can also allow us to feel our Created-ness and dependence. This doesn’t negate the benefits of going out into a dark place with little light pollution and watching the stars, or from taking a hike to an overlook. But it is a little bit of an artificial experience of dependence.

For many Christians, the cost of discipleship hasn’t felt particularly steep. When we are autonomous and well-off and self-made, there is less space for the appreciation of and awe around our interaction with the divine. We may find that the spiritual depths that come through hardship must be practiced through disciplines such as fasting. Lent has been a time when we could identify with our dependence and finitude. Fasting from something we usually have a lot of can help us shrink down our lives and to see what we really need.

We can look to find more wilderness in our domesticated spiritual lives and cultivate that sense of wonder as God works to protect, comfort, inspire, and renew us. Lent might be a good time for that.