[This is the third part in a three-part series that delves into the story of Zion, Illinois, and its founder, John Alexander Dowie. This series explores the oft-misunderstood relationship between charismatic Christianity and modernity. Click here for the first part, or here for the second part.]

They had removed two of the three bullets from his body, but Senior Sergeant Sauer was now refusing further treatment.

“Do not touch me,” he said, “I want no drugs. Telephone Dr. Dowie and ask him to pray for me!”

A few of the nurses offered nervous laughs, unsure what to say. The surgeon could not retrieve the deeper bullets without some sort of sedative or pain reliever being administered, and the man would not take anything.

Sauer entered the gap, “God is the Healer, and Jesus is still the same. Ask Dr. Dowie to pray.”

Partly bemused, partly resigned, one of the nursing staff walked to the nearby telephone and picked up the earpiece. That church was across from the husk of the burned-out fairgrounds. Services ran almost every night. Someone would pick up.

“Zion Tabernacle, please.”

Alexander Dowie is remembered for many things: cult-like devotion, staged healings, fancy robes, and securities fraud, to name just a few. In short, he is recalled for his extremities and abuses. He—and His Zion—are cautionary tales; they are emblems of excess and zealotry, of hucksterism and a particular strain of American utopian delusion. This is unfortunate.

In treating them this way, we can easily miss their broader importance for global religious history writ large. Dowie may have been a saint or a charlatan; Zion might have been a scam or a utopia. Regardless, they were signs of things to come.

For me, what their story illustrates is the importance of the emerging synergistic power of media and communication at the turn of the century.

Dowie, the First Tel-Evangelist

If Dowie was a genius at anything, it was publicity.

Early in his career, Dowie had developed a knack for generating local and national publicity. Through editorials, public spectacle, and pamphlet wars, Dowie learned to draw people’s attention to himself. While his critics might have called his tracts “ill-printed, ill-written, and ill-looking,” they nonetheless drew a crowd, and Dowie would not forget the power of the printed word. By 1890, he established himself in America and began printing the Leaves of Healing newspaper to connect his growing trans-Pacific faith healing organization. In 1894, he established the Zion Publishing House and began pumping out millions of pages of print. The publishing house would go on to print book after book, several more English-language newspapers, and translations of Leaves in German, Dutch, Swedish, and French.

The embrace of print within turn-of-the-century evangelical circles was common. Everyone believed in the power of print, but not everyone understood the ways it could be combined with other forms of communication to foster even deeper senses of personal connection. This was what Dowie understood intuitively.

A quick browse through Leaves reveals an unrivaled interest in the newer technologies of telegraphy and telephones. Through testimonies and verbatim instructions, Dowie insisted that readers of his papers should use these technologies to contact him (or at least his offices) with their prayers, their testimonies, and their wallets. When telephone calls were received, Dowie affirmed how “touching” it was “to hear the ringing, grateful sound of the hearty “Amen” from the friends in distant cities.” When he received telegrams, he responded with an hour that he would pray for the afflicted, and testimonies later affirmed that healing came at just that hour. In short, these new modes of communication allowed Dowie to develop personal connections with individuals across vast distances, to collapse space and time, and to create a community focused on his brand of faith healing, his various enterprises, and his cult of personality. As Senior Sergeant Sauer’s story illustrates, people were willing to bet their lives on those connections.

This cross-platform, engagement-driven approach formed a playbook that every future televangelist—or politician and social media influencers for that matter—would eventually come to know well.

Zion’s Grapho-Tele-Phone and World-Wide Theocracy

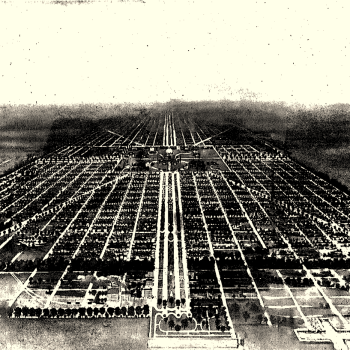

Obviously, this playbook meant that Dowie’s utopian Zion City was all but required to have its own “perfect system” of telephones and telegraphs, where every resident could have a phone line, if they desired. Erected without the aid of outside companies, Zion’s system was “installed and maintained” by its own electrical engineers. This ensured that no one could deny them access to the wires over doctrinal or legal disputes (an issue Zion faced when the British government denied them access to the South African wire system).

The importance of the wires was underscored by the mythical founder’s own presence in the city. While Zion was founded in 1900, Dowie did not relocate until after the telecommunication wires were connected to Chicago in 1902. After some haggling with the Chicago Telephone Company, Zion was connected directly to the world by 1903, and Dowie could triumphantly write that his home telephone allowed him to be “in communication with… every part of the civilized world,” and that “modern science, invention and progress have made possible the establishment of a world-wide Theocracy.”

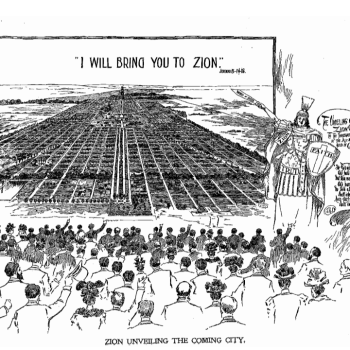

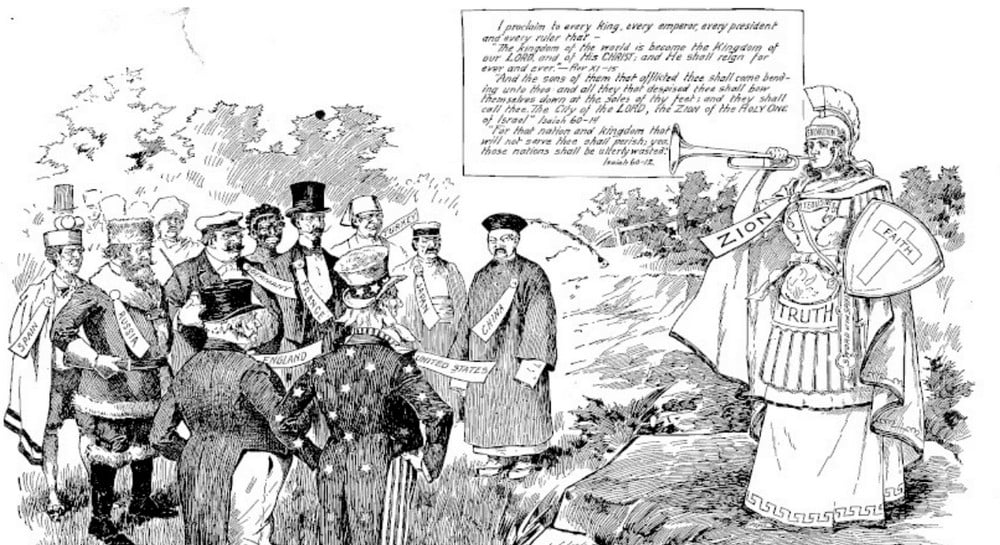

Zion was the center of Dowie’s increasingly grandiose vision of worldwide influence. After his 1901 declaration of himself as the spiritual return of Elijah, Zion’s periodicals began to increasingly focus on the concept of Theocracy. Ideally, the concept meant a form of “government of the people by immediate direction of the Almighty.” In practice, it meant an even more autocratic form of leadership centered on Dowie, who wielded almost absolute authority over the financial, governmental, and ecclesiastical arms of his now global Christian Catholic Apostolic Church in Zion.

No longer a global fellowship dedicated to faith healing, Dowie’s Church was part of God’s end-time vision for the world, and Zion City was an essential part of that vision. It was to be the first of many.

This Zion is being established by God as the first of many Zion Cities. From these Zion Cities shall flow back to that Ancient Zion, the Glory of all the Nations, the Chosen from the Twelve Tribes of God’s Israel, the best, the purest, the holiest, the strongest, the noblest of the redeemed, until they stand with the Lamb on Mount Zion.

He then proclaimed that these cities were the 144,000 referred to in the Book of Revelation.

Here again, it is tempting to think about Dowie in his obvious excesses, but to do so would miss the ways he was a harbinger of things to come (just not the things he thought).

Dowie’s end-time vision was of a global fellowship of holy cities and holy people, united across race, class, and gender. It was a form of what Joel Cabrita called Christian cosmopolitanism, where all distinctions and diversities were subsumed into one Christian community. Zion was intended to be the “metropolis of the Universe,” and for a time, it seemed like it might be. Zion City had people representing nationalities from over 60 nations, and the Zion message was growing rapidly among black South African peoples. Dowie even hoped that the emerging technology of wireless telegraphy [radio] might help spread his message to Mars and any unsaved people who might be there.

Dowie’s global (and Martian) vision illustrates his belief that innovations in telecommunication were a form of divine Providence, that these technologies were part of God’s plan, visible manifestations of His power. In one particularly flowery ode to innovation in 1901, Dowie lionizes the power of the printing press and extols the even greater power of telegraphy and telephones. Then, he looks to the future. I include the extract in full because it is simply too glorious:

We see another great Power beginning to appear, by means of which, we cannot doubt, the Printing Press will be gloriously supplemented. It is the Grapho-Tele-Phone, by means of which the songs sung and the words spoken in Zion Temple, and even in our Editorial Room, will be recorded upon cylinders and transferred, as is even now done, to hundreds of thousands of other cylinders, and also transmitted by electric wires to earth’s remotest bounds, so that not only will Zion read, but Zion will one day hear, the words spoken in Zion Temple and elsewhere. … How glorious will it be when the King Himself, therefore, shall come, and His redeemed o’er all the Earth shall hear, as well as read His Messages. … The graphophone and telephone may soon find their completion in photo-telegraphy, so that the words spoken shall not only be transmitted, but the speaker himself be seen, and every gesture and every look shall be imperishably imprinted, preserved, and transmitted o’er all the earth. … All hail to the Printing Press and all its beautiful adjuncts, and all hail to the coming Grapho-Tele-Phone and Photo-Telegraph-the Speech-Recorder and Transmitter, and the Picture-Producer ! We hope that Zion City will yet produce that glorious combination…

If the telephone rendered, “time and space … bridged by the use of these Wonderful Invisible Powers,” then the grapho-tele-phone and photo-telegraphy would make the circulation of information practically instantaneous. Just as telegraphs and telephones allowed Dowie to create a worldwide network, the technologies of the future would allow him, as God’s messenger, to rule it. Even the end-time vision of Christ’s return is cast in technological terms. Of course, the Coming King will issue decrees on the grapho-tele-phone, and of course, Zion City would have one.

Techno-utopias and Our Failed Visions

Dowie, of course, was not quite right. Christ has not returned just yet, and the grapho-tele-phone was not just around the corner. That said, I do have something like a grapho-tele-phone in my pocket as I write, and I cannot be quite sure of Christ’s communication preferences on the Day of Judgment. Dowie did not create a new techno-divine world order, but he did foreshadow the modern televangelist and the social influencer, potent and enduring orders all their own.

Similarly, Dowie’s Zion was intended to be a techno-utopia, a place where the best of technology, human engineering, and holy living created a new way of life. It was and it wasn’t. Soon after his death in 1904, the city faced bankruptcy and was quickly fractured as succession crises roiled the organization. The city never fully embodied the careful plan that its Chief Engineer, Burton J. Ashley, imagined. Still, it was an early sign of the future suburban sprawl, of carefully manicured lawns, home telephones, and easy commutes into the city.

And, of course, the interconnected network of Zion Cities never came into being. With Dowie’s Elijah Declaration and then death, the global fraternity of Zion churches broke apart as generational and leadership disputes ruptured communions and the nascent Pentecostal movement tore through the network, especially in South Africa. Nevertheless, Zionism remains one of the most important strains of charismatic Christianity in Africa today.

In her work, When the Medium Was the Message, Jenna Supp-Montgomerie argued that religious actors helped form modern network culture and our very conceptions of network technology. Dowie and Zion exemplify this same dynamic. Like so many of their peers, Dowie and his followers believed that technology could translate directly to divine destiny. Progress was possible if only it could be harnessed to the right ends. They did harness it, but not to the ends they imagined.

If there is a lesson in Dowie and Zion, it is perhaps this: The effects of technological change on religious communities are not so easy to predict, but they are important. If we do not pay attention to these relationships, then we run the risk of misunderstanding Dowie, Zion, and even Christianity today.