Welcome to this fourth installment of Death Wednesday here at the Anxious Bench. In my last post I described the nostalgic appeal of Trappist caskets and old-time burial practices at the bucolic Abbey of Gethsemani. For me and my students, Gethsemani seemed awfully appealing as we contemplated the likelihood of our own deaths in an antiseptic hospital while harnessed to a machine.

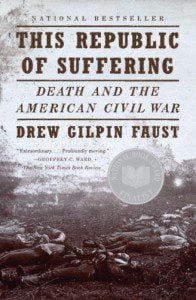

For nineteenth-century Americans, the notion of death outside the home was inconceivable. Historian Drew Gilpin Faust describes this sensibility in her terrific–and grisly–book, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War. (I highly recommend this book for the classroom—students are fascinated by it.) Faust shows how ars moriendi, or “the good death,” was scripted in several important ways. First, it was important to die at home. Hospitals housed the indigent. Respectable people died in more comfortable surroundings among affectionate family. In fact, as late as 1910, fewer than 15% of Americans died away from home. Second, it was important not to die suddenly. Antebellum Christians wanted to see the end approaching, to accept it, and then declare to friends and family their belief in God and his promise of salvation. This “dying declaration” was accompanied by words of moral guidance for those left behind.

For nineteenth-century Americans, the notion of death outside the home was inconceivable. Historian Drew Gilpin Faust describes this sensibility in her terrific–and grisly–book, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War. (I highly recommend this book for the classroom—students are fascinated by it.) Faust shows how ars moriendi, or “the good death,” was scripted in several important ways. First, it was important to die at home. Hospitals housed the indigent. Respectable people died in more comfortable surroundings among affectionate family. In fact, as late as 1910, fewer than 15% of Americans died away from home. Second, it was important not to die suddenly. Antebellum Christians wanted to see the end approaching, to accept it, and then declare to friends and family their belief in God and his promise of salvation. This “dying declaration” was accompanied by words of moral guidance for those left behind.

The Civil War interrupted rituals of the good death. Industrialized war was deadly, unpredictable, and excruciatingly painful. Death came far from home and was often delivered by explosive artillery shells, which sometimes left no identifiable remains. The terrifying isolation, inconceivable volume, and painful intensity of modern martial death seemed utterly absurd to nineteenth-century Americans. Armies, of course, tried to cope with this new style of death. Nurses acted as substitute kin by eliciting dying declarations and cueing them through rituals of ars moriendi. Fellow soldiers recorded last words and sent them to family at home. They even read corpses. “His brow was perfectly calm,” described one letter. “No scowl disfigured his happy face, which signifies he died an easy death, no signs of this world to harrow his soul as it gently passed away to distant and far happier realms.” Clearly such a face could not be on its way to hell!

Industrial-style death, of course, only accelerated after the Civil War. The twentieth century was one of the most violent centuries in history as humans found novel ways to kill each other. Consider this depressing litany: a world war from 1914 to 1918 that killed 37 million civilians and soldiers; a world war from 1939 to 1945 that killed 60 million people (nearly 3% of the world’s population); the genocide of two million Cambodians in the killing fields of one nation alone; the annihilation of 140,000 Japanese civilians from a new and awful nuclear weapon; and the deaths of millions because of unhealthy manufactured foods. All this in a modern era that promised freedom and health. The pervasiveness of death and destruction in the early twentieth century was enough to return theological liberals who liked to speak of human goodness back to the concept of original sin.

Even the Trappists, despite slow lives in rural enclaves, have not been immune to the ravages of modernity. Thomas Merton died in a bizarre accident in Bangkok. Attending a global conference for Trappist abbots, he was electrocuted by a five-foot standing fan in his hotel room. Merton’s scarred body was flown back to the United States in a jet alongside American soldiers killed in Vietnam. No one on that plane enjoyed a slow, contemplative death surrounded by family.

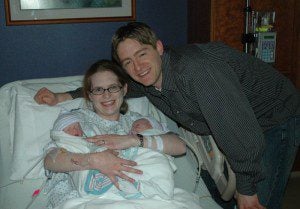

I don’t want to over-romanticize premodern death. Medicine and more sophisticated understandings of biology and chemistry have given more years of fulfilling life for many people. Just after my wife Lisa gave birth to twins several years ago, she began to hemorrhage blood. I’ve never seen doctors bark orders so loudly, nurses move so quickly, and chemicals get pumped into a person so urgently. It was a terrifying couple of minutes. She almost surely would have died a century ago. Modern death might be unappealing, but I wouldn’t trade it for a nineteenth-century “good death”—at least not while we’re in our thirties!