It’s grim to watch recent developments in Egypt, as the nation’s Coptic Christians face growing threats.

Not that Egypt’s long-suffering Muslim majority does not deserve full sympathy and respect, but the Copts stand in a very special place in the Christian story. So central are they, in fact, that I sometimes fantasize about writing a History of Christianity from the Egyptian perspective. Without Egypt, we would miss so many critical turning points in the making of the Christian faith. My next few posts will cover some of those issues and moments.

Before Christianity, Egypt held a special place in Jewish hearts. As early as the fifth century BC, Jewish settlers at Elephantine were operating a full-scale Temple, of a kind not theoretically supposed to exist outside Jerusalem.

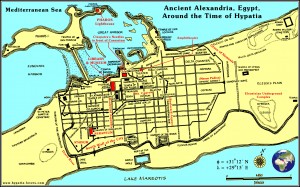

Alexandria was the capital of the Jewish Diaspora, the world’s second largest Jewish city, and almost certainly the center where the Septuagint was translated. By the first century AD, the city had five quarters, two of which were mainly Jewish. During Jesus’s lifetime, Philo was the towering giant of that Hellenistic world, the genius who integrated Greek philosophy into the Jewish world-view. Among other contributions, his concept of the Logos would have a staggering philosophical afterlife.

This Jewish context made it inevitable that Christianity would make very early inroads into Egypt: only three hundred miles separate Jerusalem and Alexandria. Followers of Jesus presumably arrived here very shortly after his death, if not before. For reasons I will discuss later, we know little of the very early Christian presence, but that soon became very marked, and influential.

We are often uncertain where exactly ancient books and manuscripts might have been produced, and the fact that a writer reflects particular ideas does not mean where he or she was actually located. Having said that, ideas and language that seem to derive from Hellenistic Egypt are strongly marked in some early Christian writings, including the Gospel of John, and in texts like the Epistle of Barnabas.

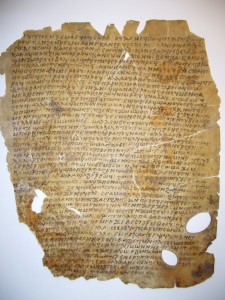

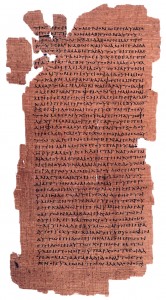

Also, the fact that Egypt had so many libraries and monasteries in a very dry climate means that the country has been a treasure trove of ancient document finds, from Oxyrhynchus a century ago to the Nag Hammadi library and the Bodmer Papyri in mid-century. St. Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai was for many centuries the home of the glorious Codex Sinaiticus.

If we can’t be sure just where these most of these various texts were written, we can certainly say that they circulated in Egypt, and contributed to the making of an extremely rich and diverse Christian culture there between, say, 100 and 500.

If we just look at the period 200-500, the volume of achievements becomes simply breathtaking. The third century was the era of Origen, certainly a candidate for the title of the most brilliant and daring scholar in Christian history. By the end of that century, Egypt became the home of the monastic movement, which would transform the faith worldwide, and lay the foundation for the making of medieval European civilization.

In the fourth and fifth century, the patriarchs – popes – of Alexandria were pivotal to the church debates and councils that established Christian orthodoxy for centuries to come. This was the era of Athanasius and Cyril, of the Councils of Nicea, Ephesus and Chalcedon. Underlying the theological debates was a more basic question, of Alexandria’s aggressive and daring claims of to a kind of supremacy over the wider Christian world.

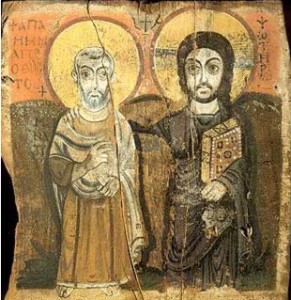

Finally, Egyptian Christians of this era contributed powerfully to creating the Christian visual imagination, as they developed the tradition of icon painting.

Memories of older depictions of the goddess Isis and her son Horus were transformed into the wildly popular image of the Virgin Mary and her divine Son, soon to be seen wherever Christians prayed.

In the sixth century, Severus of Antioch complained that “Alexandrians think the sun rises just for them.” But why shouldn’t they? Egyptians had already done so much to establish Christian culture, art and intellectual life. They made the faith we know.