Last week, my friend Sara Shady used this space to suggest how Christians might learn from Martin Luther King, Jr. in the wake of the murder of George Floyd and the protests, riots, and calls for systematic reform that have ensued. As she compellingly argued, Christians today tend to view MLK through two lenses, taking comfort from the image of a peaceful marcher while looking away from the violence inflicted on a social activist whose wise words demanded radical action.

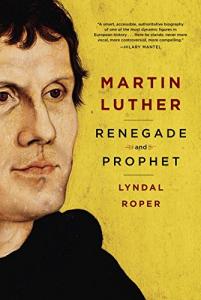

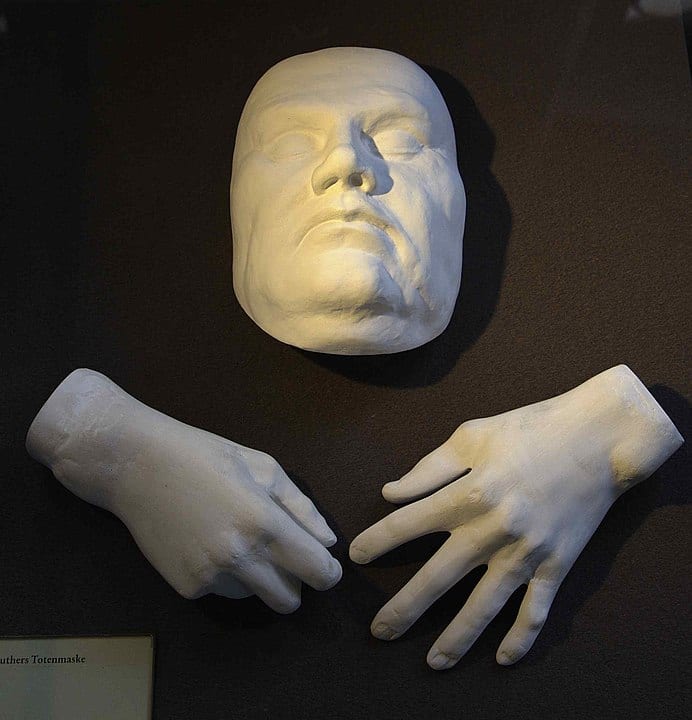

As I read Sara’s thoughtful reflection, I wondered if a variation on that theme happens with the Protestant reformer for whom MLK was named. Like Martin Luther King, Jr., contemporary Christians often look to Martin Luther “not only for wisdom, but for comfort” — as in the case of his 1527 letter about a pandemic. And they often look away from the violence that Luther’s words inspired, condemned, and sanctioned.

But if we share MLK’s commitment to justice, we should find ML’s commitment to order uncomfortable — and ultimately inconsistent.

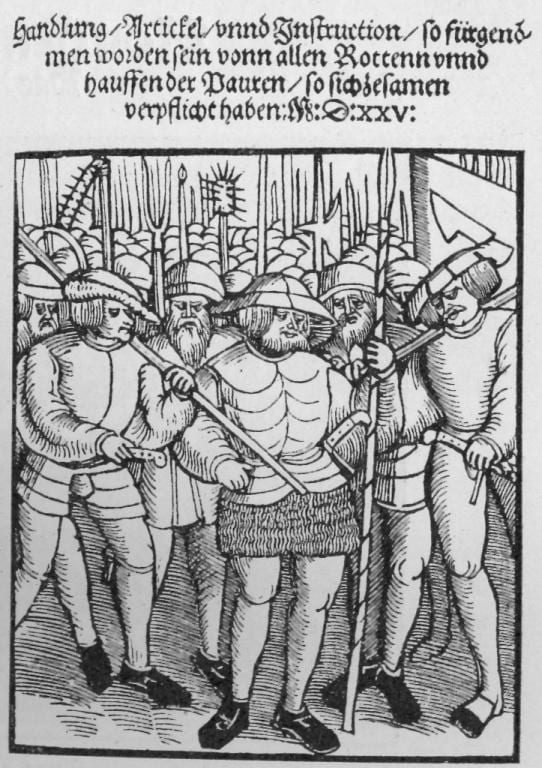

In 1524, farmers, artisans, and other Germans organized themselves for an armed rebellion against some of the same authorities before whom Luther had refused to recant his beliefs three years earlier, at the Diet of Worms. It was the largest of many late medieval revolutions, but the German Peasants’ War (sometimes called the “Revolution of the Common Man” — it wasn’t confined to rural workers) took particular inspiration from Luther’s reformation. In a 1525 manifesto, peasants in the region of Upper Swabia called for both religious reform (e.g., the right of the community to choose its pastor and hear preaching by Scripture alone) and social and economic change. “It has been the custom hitherto for men to hold us as their own property,” lamented the authors of those Twelve Articles, “and this is pitiable, seeing that Christ has redeemed and bought us all with the precious shedding of His blood, the lowly as well as the great, excepting no one.”

If their proposed tax, land, and rent reforms were proved “not to be in agreement with the Word of God,” the peasants accepted that such demands would be “null and void, and have no more force.” But they believed that they had sola Scriptura on their side. After all, did they not cry out to the same God who had heard the pleas of the Jews in Egypt and liberated them from slavery? And “if it be the will of God to hear the peasants, earnestly crying to live according to His Word, who will blame the will of God?”

In that sense, the Peasants’ War was an early, European outworking of a theme that Mark Noll observed in recent American history on the 500th anniversary of the 95 Theses:

The willingness of Martin Luther to stand before the emperor Charles V at Worms in 1521 in some sense was an inspiration for the civil rights leaders, Martin Luther King Jr. and others, to stand forthrightly against centuries of segregation tradition and to proclaim what they thought was not just an ethical truth, but the word of the Lord.

But, Noll added, Martin Luther held “a very different ethic [than] that Martin Luther King held when he felt that there was something amiss in society.”

Proposed by the peasants as an arbiter for their grievances against the ruling classes, Luther initially responded to the Twelve Articles with an “Admonition to Peace.” It began by acknowledging the justice of some of the peasants’ complaints: “We have no one on earth to thank for this disastrous rebellion” except temporal rulers whom he accused of doing “nothing but cheat and rob the people so that you may lead a life of luxury and extravagance.” But “the fact that the rulers are wicked and unjust does not excuse tumult and rebellion, for to punish wickedness does not belong to everybody, but to the worldly rulers who bear the sword.”

Quoting from Romans 13, Luther warned the peasants that revolt against secular authorities constituted a revolt against God. (As I’ve noted previously, Loyalist opponents of the American Revolution and slaveholding opponents of abolitionism used the same proof-text.) Luther appealed to the Sermon on the Mount to urge the peasants not to “rage and struggle against the divine and natural law… not to resist any evil or wrong, but always yield, suffer it, and let things be taken from us.”

As the rebellion grew more intense, Luther took an even harsher tone. In a polemic some printers titled “Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants,” he abandoned hope for a peaceful settlement. Because the rebels had damaged property (“monasteries and castles that do not belong to them”), they deserved “the twofold death of body and soul….

As the rebellion grew more intense, Luther took an even harsher tone. In a polemic some printers titled “Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants,” he abandoned hope for a peaceful settlement. Because the rebels had damaged property (“monasteries and castles that do not belong to them”), they deserved “the twofold death of body and soul….

Every man is at once judge and executioner of a public rebel; just as, when a fire starts, he who can extinguish it first is the best fellow. Rebellion is not simply vile murder, but is like a great fire that kindles and devastates a country; it fills the land with murder and bloodshed, makes widows and orphans, and destroys everything, like the greatest calamity. Therefore, whosoever can, should smite, strangle, and stab, secretly or publicly, and should remember that there is nothing more poisonous, pernicious, and devilish than a rebellious man. Just as one must slay a mad dog, so, if you do not fight the rebels, they will fight you, and the whole country with you.

“For we are come upon such strange times,” Luther concluded, “that a prince may more easily win heaven by the shedding of blood than others by prayers.” If he was right, much heaven was won, for the princes of Germany shed much peasant blood: tens of thousands were killed before the revolt ended in 1526.

Whatever you think of that outcome, Luther at least seems consistent in his interpretation of the purposes of political authority. In his “plague letter” a year after the revolt, Luther called it “a great sin” for secular authorities to save their own lives and “abandon an entire community which one has been called to govern….” For an ungoverned city was “exposed to all kinds of dangers such as fires, murder, riots… the kind of disaster the devil would like to instigate wherever there is no law and order” (emphasis mine).

Of course, as we heard from Tom Skinner last week via David, it is all too easy for Christians who benefit from the status quo to invoke the language of “law and order.” Those of us who instinctively dislike disorder should consider that what Skinner preached in 1970 also describes 2020 — or 1520:

The whole existing human order is infested with ungodliness. And the whole purpose of Christ coming into the world was to overthrow the demonic human system and to establish his own kingdom in the hearts of men.

And appeals to “law and order” like Luther’s (which cast the peasants’ rebellion as “demonic”) are rarely consistent: if not hypocritical, at least selectively applied. For Martin Luther ended up sanctioning violent resistance against those in power — for the sake of protecting his religious reformation, though not to address economic inequality and social injustice.

As the same Protestant princes who had crushed the Peasants’ War began to organize armed resistance against their own emperor, Charles V, Luther began to find some rebellion justifiable. In 1531, he urged German Christians to refuse to fight for Charles, whose mistreatment of the Protestant cause was action “not only against God and divine law, but also against his own imperial laws, oaths, duty, seals, and letters.” At that point, Luther still urged peace, but as a religious civil war drew nearer, he grew less cautious with his rhetoric.

In the last years of his life, Martin Luther endorsed the position that Protestant princes were obliged to maintain — even by violence — “the true external service of God against all unjust power”— even that of the emperor. But he went even further, as in this 1538 table talk, and entertained the possibility that individuals were allowed to wield the sword against a ruler using his God-given authority unjustly:

If the emperor undertakes war he will be a tyrant and will oppose our ministry and religion and then he will also oppose our civil and domestic life. Here there is no question whether it’s permissible to fight for one’s faith. On the contrary, it’s necessary to fight for one’s children and family.

The heirs of Martin Luther have wrestled with the tension ever since. In American history, for example, white Protestants convinced themselves that Romans 13 justified violent rebellion against tyrannical kings and parliaments — but not violent insurrections by enslaved Africans.

Nothing that’s happened in this country in the past two weeks has begun to approach the violence of those episodes, or the German Peasants’ War. Yet I still find myself instinctively recoiling from images of even modest social disorder. Perhaps I need to listen less to the words of Martin Luther and more to those of the peasants he condemned. For if it be the will of God to hear Black Lives Matters protestors earnestly crying to live according to his Word, who will blame the will of God?