One year ago, in my post God’s Christmas Gift to Women, I reflected on how a nativity sermon written by the late medieval preacher John Mirk reveals the significance of God choosing Mary. As I wrote, “the Christmas story tells women we are more. Because God used Mary to be the mother of Jesus, God made sure that women would always have a seat at the Christian table. Because of Christmas, women can never be written out of God’s story.” Yet history shows us how often Christians have written women out of God’s story–downplaying and even ignoring women’s roles in church history. Isn’t it interesting that many of these same Christians have also downplayed Mary? The medieval Jesse Tree, combined with a new book about the Virgin Mary, inspired me to revisit what I wrote last year.

The train platform in Shrewsbury, Shropshire (UK) is narrow and long. Sometimes it is hard to tell the end of one train from the beginning of the next. Once I was confused enough to step into the wrong carriage. I was tired from a long day of archival research and, as soon as I sat down, I fell asleep. Which means I missed that we were heading in the wrong direction. Instead of making my way back to Birmingham, I woke up in Aberystwyth.

The train platform in Shrewsbury, Shropshire (UK) is narrow and long. Sometimes it is hard to tell the end of one train from the beginning of the next. Once I was confused enough to step into the wrong carriage. I was tired from a long day of archival research and, as soon as I sat down, I fell asleep. Which means I missed that we were heading in the wrong direction. Instead of making my way back to Birmingham, I woke up in Aberystwyth.

Luckily this mistake didn’t put me off traveling to Shrewsbury. It remains one of my favorite places in England. I just look more carefully at the platform signs.

It is true that the Shrewsbury rail station is neither as grand nor as ideally situated as it once was. From the imitation Tudor style building constructed in 1848 to its location on the outskirts of town (literally at the bottom of the hill), the station reflects more Shrewsbury’s past then present. But it is also true that entering Shrewsbury from the train station provides a great introduction to the medieval city. Just cross the car park and take a left. You will see what I mean.

The steep incline of the hill on the narrow Castle Gates road–lined on both sides with crowded buildings liberally sprinkled with black and white timber frames–evokes a past world. Did you know that Shrewsbury boasts one of the best preserved layouts of medieval streets in all of England? The red sandstone walls of the remodeled 11th century castle (which lends its name to the street) beckon camera shots just as does the castle’s neighbor, a large Elizabethan town house built on Dogpole street in 1620 and moved to its present location on Castle Gates in 1696 (to house a lord’s mistress, but that is a story for another day…).

I would like to say that, since I have walked up this street so often, I no longer pause to gawk and take pictures. But that wouldn’t be true. I always pause–especially when I reach the top of the hill. Today, a War Memorial marks the spot where the old market cross once stood. I always turn left here, walking quickly from the highest point of town to one of the oldest sections of town: St. Mary’s Place. Around 970, King Edgar dedicated the old Saxon church here (possibly founded as early as the 7th century) to St. Mary the Virgin, the Mother of God.

I would like to say that, since I have walked up this street so often, I no longer pause to gawk and take pictures. But that wouldn’t be true. I always pause–especially when I reach the top of the hill. Today, a War Memorial marks the spot where the old market cross once stood. I always turn left here, walking quickly from the highest point of town to one of the oldest sections of town: St. Mary’s Place. Around 970, King Edgar dedicated the old Saxon church here (possibly founded as early as the 7th century) to St. Mary the Virgin, the Mother of God.

There is so much I could tell you about St. Mary’s. I could tell you how the church was important enough to be included in the Domesday Book of William the Conqueror in 1087. I could tell you how it is the most intact medieval church in Shrewsbury. I could tell you how, despite one lightning strike and two earthquakes, the 15th century Perpendicular-style spire still ranks as the third tallest in England–helping inspire A.E. Housman’s immortal words: “High the vanes of Shrewsbury gleam/ Islanded in Severn Stream.” But I want to tell you about St. Mary’s magnificent medieval stained glass, specifically the Jesse Window.

enough to be included in the Domesday Book of William the Conqueror in 1087. I could tell you how it is the most intact medieval church in Shrewsbury. I could tell you how, despite one lightning strike and two earthquakes, the 15th century Perpendicular-style spire still ranks as the third tallest in England–helping inspire A.E. Housman’s immortal words: “High the vanes of Shrewsbury gleam/ Islanded in Severn Stream.” But I want to tell you about St. Mary’s magnificent medieval stained glass, specifically the Jesse Window.

No so long ago my daughter brought home a Jesse Tree craft. She carefully unpacked it from her back pack, showing me each of the symbols and telling me the biblical stories they represented (at least those she could remember). I confess I was taken aback. “This is a Jesse Tree?,” I asked  her, holding up an image of a burning bush. “Yes, mom,” she said. “A Jesse Tree.” I didn’t argue with her. I learned that the Jesse Tree, in the form of my daughter’s hand-colored ornaments, was a modern Christmas phenomenon. From Amazon to homeschool blogs, the internet is full of Jesse Tree crafts. They teach the biblical stories, from Old Testament to New, leading up to the birth of Jesus. Each ornament depicts a symbol of the story it represents (such as an apple representing the Fall), and one is hung each day of advent on a tree, culminating in an image of a baby in a manger or the nativity scene (Mary, Joseph, and baby Jesus).

her, holding up an image of a burning bush. “Yes, mom,” she said. “A Jesse Tree.” I didn’t argue with her. I learned that the Jesse Tree, in the form of my daughter’s hand-colored ornaments, was a modern Christmas phenomenon. From Amazon to homeschool blogs, the internet is full of Jesse Tree crafts. They teach the biblical stories, from Old Testament to New, leading up to the birth of Jesus. Each ornament depicts a symbol of the story it represents (such as an apple representing the Fall), and one is hung each day of advent on a tree, culminating in an image of a baby in a manger or the nativity scene (Mary, Joseph, and baby Jesus).

Almost every blog post describing these Jesse Tree crafts note that it was a medieval tradition–rooting their modern practice in medieval Christianity.

Yet, as a medieval historian, I have to tell you that medieval Jesse Trees look different.

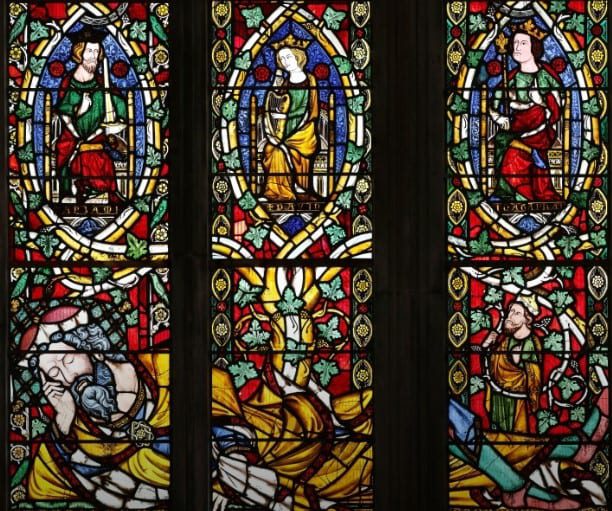

Take the Jesse Window at St. Mary’s in Shrewsbury. Originally designed in the fourteenth-century for the Franciscan friary in Shrewsbury, it wa s moved to the nearby church of St. Chad’s during the Reformation (to protect it during the Dissolution of the Monasteries by Henry VIII) and (when St. Chad’s collapsed) moved again to St. Mary’s (it is about 60% medieval glass). Rather than reflecting images of bible stories, this Jesse Tree depicts the ancestry of Christ–starting with the root of Jesse (Isaiah 11:1), blooming upward through the genealogy of Matthew 1:1-16 (with additions from Luke 3:23-38), and culminating in the Virgin Mary and Jesus.

s moved to the nearby church of St. Chad’s during the Reformation (to protect it during the Dissolution of the Monasteries by Henry VIII) and (when St. Chad’s collapsed) moved again to St. Mary’s (it is about 60% medieval glass). Rather than reflecting images of bible stories, this Jesse Tree depicts the ancestry of Christ–starting with the root of Jesse (Isaiah 11:1), blooming upward through the genealogy of Matthew 1:1-16 (with additions from Luke 3:23-38), and culminating in the Virgin Mary and Jesus.

While the spirit of modern Jesse Trees (depicting the biblical steps to Jesus) match the medieval tradition, t he medieval presentation of these ideas is different. Rather than symbols, medieval artists focused on people–the human lineage of Christ. Medieval artists also highlighted a figure much less visible in modern Jesse Trees–the mother of God. Just look at a few of the examples of medieval Jesse Trees here and here. Isn’t it striking? While the lineage of Jesus overflows with men in medieval depictions of the Jesse Tree, the central image is often that of a woman: Mary. Sometimes she is depicted directly beneath the image of Jesus (here also); sometimes she is depicted holding the infant Christ (such as at St. Mary’s); and sometimes she is depicted as the most prominent figure on the tree, as Queen of Heaven (and in the Jesse Window at York Minister).

he medieval presentation of these ideas is different. Rather than symbols, medieval artists focused on people–the human lineage of Christ. Medieval artists also highlighted a figure much less visible in modern Jesse Trees–the mother of God. Just look at a few of the examples of medieval Jesse Trees here and here. Isn’t it striking? While the lineage of Jesus overflows with men in medieval depictions of the Jesse Tree, the central image is often that of a woman: Mary. Sometimes she is depicted directly beneath the image of Jesus (here also); sometimes she is depicted holding the infant Christ (such as at St. Mary’s); and sometimes she is depicted as the most prominent figure on the tree, as Queen of Heaven (and in the Jesse Window at York Minister).

Mary plays a central role in the medieval Jesse Tree that seems different from modern depictions. This is clearly seen in the 14th-century Jesse window at St. Mary’s. Fifty-three panels  make up the story of this medieval window. Forty-six of these panels (omitting only the medieval donors of the windows and the panel paying homage to the English king Edward III) display the life of Jesus, the lineage of Jesus, and the Old Testament Prophets. The only figures to appear more than once are Jesus (4 depictions) and Mary (3 depictions). Mary’s presentation of the infant Christ to her mother St. Anne (a popular medieval story) is one of only three moments depicted from the life of Jesus, alongside his baptism and crucifixion. While I cannot guarantee that Mary’s image was centrally located in the medieval window as it is now in the restored window, I can guarantee that Mary was centrally located within most medieval Jesse Trees.

make up the story of this medieval window. Forty-six of these panels (omitting only the medieval donors of the windows and the panel paying homage to the English king Edward III) display the life of Jesus, the lineage of Jesus, and the Old Testament Prophets. The only figures to appear more than once are Jesus (4 depictions) and Mary (3 depictions). Mary’s presentation of the infant Christ to her mother St. Anne (a popular medieval story) is one of only three moments depicted from the life of Jesus, alongside his baptism and crucifixion. While I cannot guarantee that Mary’s image was centrally located in the medieval window as it is now in the restored window, I can guarantee that Mary was centrally located within most medieval Jesse Trees.

Indeed, Mary is highlighted in medieval churches in a way that she is not among modern Protestants. As I wrote last year:

In a world that told women they were less than men, the Christmas story told medieval women something different. As one late medieval preacher wrote, “The daughter of Eve was the beginning of damnation for mankind; [but] the faith of women in the new law was the beginning of salvation for mankind. The faith of Our Lady Saint Mary was the beginning of salvation for our world,” (Longleat House MS. 4, folios 35v-37v). For medieval people, a woman was not only part of God’s salvation plan; she was crucial to its success.

Like in modern Jesse Trees, however, Mary today is relegated to a smaller role. I am a self-identified evangelical, which means I do not believe in teachings about Mary’s immaculate conception, perpetual virginity, nor (potential) role as co-redemptrix. I believe Jesus alone saves. But I can’t help but wonder about the implications of deemphasizing Mary? By limiting Mary, have we also limited women?

In her new book, The Virgin Mary’s Book at the Annunciation, Laura Saetveit Miles argues that doctrinal differences only account for part of why Protestants deemphasize Mary. The medieval Mary presented a sophisticated intellectual model for women as readers and spiritual instructors whose very bodies had the power to conceive of God. “Physical conception of the Word,” writes Miles, “grants Mary immediate authority in the scholastic realm of letters, texts and books, otherwise generally closed to women; through her maternal body she becomes exempt from the patriarchal requirements that make ‘maistres’ out of men” (144). For medieval Christians, Mary’s conception of Jesus authorized her as a spiritual and intellectual teacher. She was “incredibly powerful” in a way that did not survive the Protestant Reformation. “Protestant aversion from Mary was never merely doctrinal; it was often a thinly veiled outlet for misogyny,” writes Miles. “Certainly some medieval clerical authorities had always felt threatened by and sought to control this female independence linked to Mary…but the Reformation witnessed a stark shift to zero tolerance for female ‘overreach’ linked to Mary. While medieval holy women such as Birgitta of Sweden and Julian of Norwich had found in Mary inspiration for asserting their own spiritual authority, reformist sermons, for instance, emphasized her humility as demonstrated by scriptural references to ‘her obedience to lawfully constituted authority'” (255-256). Rejecting the more multifaceted, independent, and powerful medieval image of Mary helped to disempower her. Could this, in turn, have helped to disempower women?

I stand by my conclusion from last year–it is impossible to write women out of God’s story. Too bad history keeps showing how much we try to do it anyway….

Merry Christmas, y’all!