It was my mother’s frequent outcry. And of course we weren’t. We were following the devices and desires of our own hearts, as the prayer book says. We were children, after all, and we had imaginations to grow and visions to seek, and our own hearts to explore. We were not born to obedience. We were not robots to be programmed. Our normalcy as young humans is why are you listening? is normal in the mouths of mothers everywhere.

Jesus, working to raise a family of disciples, has similar problems. According to Mark, he was talking to them with some urgency about hardship and suffering, and how these things were ahead of him. And ahead of them. But when he had finished and they were talking among themselves, they spoke only about glory, and how that lay ahead of them.

And this is our endless conversation, in the church. Readings, and perhaps parts of sermons, speak to us about suffering, and how it produces endurance, and how endurance produces character, and character, hope, and how hope does not disappoint us because it is God’s love poured into our hearts by the Holy Spirit. But our hearts are really held by dreams of glory, and our conversation is more about good times than challenging ones: about Fairs, Suppers, Feast Days, the Annual Foolishness we have fondly fashioned around Christmas and Easter.

And this is our endless conversation, in the church. Readings, and perhaps parts of sermons, speak to us about suffering, and how it produces endurance, and how endurance produces character, and character, hope, and how hope does not disappoint us because it is God’s love poured into our hearts by the Holy Spirit. But our hearts are really held by dreams of glory, and our conversation is more about good times than challenging ones: about Fairs, Suppers, Feast Days, the Annual Foolishness we have fondly fashioned around Christmas and Easter.

Sometimes I imagine the church as a gigantic cathedral: on one side of the rood screen are the people of God, engaging in all sorts of invented pieties of their own, from prayer beads to burying St. Joseph upside down in order to sell a house; from burning banned books (especially the Koran) to forbidding marriage licenses to same–sex couples; from cancer-healing charms to self-delusions that God wants us to indulge in shopping as long as we shop in Christian-owned stores. And on the other side of the rood screen are the clergy, insisting on rites and rituals that beguile without reforming any of these actions, urging the recitation of creeds that do not require listening to the groans and sighs of this world, that do not even require listening for the love of God.

Of course, on both sides of the screen there are exceptions, saints who illuminate our lives with their Christ light.

Of course, on both sides of the screen there are exceptions, saints who illuminate our lives with their Christ light.

Yet the conversation among us is a cacophony. In Yeats’ words: The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere the ceremony of innocence is drowned; the best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity.

The deep longing for pieties seems to be built into our nature. We long for pieties to guide our steps to the glory of God. And piety can sometimes open our hearts to mercifulness. But far more often, piety is at enmity with mercy, piety becomes a cudgel we wield against those who need our mercy the most.

Jesus openly defied pious ways and called out the pious for hiding faithless hearts. Yet the church, in all its traditions, is filled with endless pieties which are famous refusals of mercy: from the Inquisition to priestly pedophilia; from Puritan Sabbath laws to Boston’s famed censors of books and films; from Canadian and Australian Anglican institutions in which indigenous people were detained for cultural reeducation, to Irish homes for unwed mothers who were forced to give up their babies. All of these actions were done publicly in the name of piety and for the glory of God.

Jesus openly defied pious ways and called out the pious for hiding faithless hearts. Yet the church, in all its traditions, is filled with endless pieties which are famous refusals of mercy: from the Inquisition to priestly pedophilia; from Puritan Sabbath laws to Boston’s famed censors of books and films; from Canadian and Australian Anglican institutions in which indigenous people were detained for cultural reeducation, to Irish homes for unwed mothers who were forced to give up their babies. All of these actions were done publicly in the name of piety and for the glory of God.

Jesus does not urge the prevention of his own suffering. He teaches the walk that will lead him into it, and those who love him, likewise. This is, in my experience, the least acceptable teaching of Christianity. This is the teaching people walk away from.

Mark tells us Jesus spoke to them about being servants of all, as the path to the greatness of God. And he drew a child into their midst and counselled them to become like that child. That child, who was following his own curiosity, hanging around these men and their teacher, and likely disobeying his mother by doing so. That child, whose heart was not yet so set into ways that were unrelenting. That child, who was at least curious, if not merciful. Curious about what it might mean to become a man. And willing to listen to Jesus, at least a little.

Mark tells us Jesus spoke to them about being servants of all, as the path to the greatness of God. And he drew a child into their midst and counselled them to become like that child. That child, who was following his own curiosity, hanging around these men and their teacher, and likely disobeying his mother by doing so. That child, whose heart was not yet so set into ways that were unrelenting. That child, who was at least curious, if not merciful. Curious about what it might mean to become a man. And willing to listen to Jesus, at least a little.

What the child understood is not written down. Nor do we know what became of him. But we know this much: the disciples were still grasping at the meaning of Jesus’ teaching and his life, even at Easter and beyond. As we do, now.

It is not, after all, the Resurrection that boggles the mind, so much as accepting the walk to Calvary, without sending in a rescuing army, without an armory of pious opinions to give us the right to get rid of the bad guys and proclaim the glory of God, with a flag, a crown, and a prison.

It is not, after all, the Resurrection that boggles the mind, so much as accepting the walk to Calvary, without sending in a rescuing army, without an armory of pious opinions to give us the right to get rid of the bad guys and proclaim the glory of God, with a flag, a crown, and a prison.

There are an endless supply of stories about the generosity of children, yet when there are children at our borders numbering in the thousands, we close our hearts. It is the mercy of adults that is harder to find occurring in this world. As Jesus knew. Are we listening?

________________________________________________________

Illustrations:

1. Boy With His Hound. 1675. Borch, Gerard, Munich, Germany. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library. Art in the Christian Tradition.

2. Migrant Mother With Children on Arizona Highway 87. 1940. Dorothea Lange. National Archives. Library of Congress. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library. Art in the Christian Tradition.

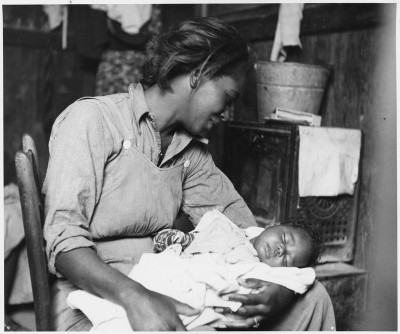

3. Migrant Cotton Picker and Her Baby. Dorothea Lange. National Archives. Library of Congress. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library. Art in the Christian Tradition.

4. Jesus Hand Reaches Out to Children. Freestanding Sculpture, Washington National Cathedral. DC. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library. Art in the Christian Tradition.

5. Destitute Boy with Wicker Basket, Poor People’s Shelter, Changsa, China. 1944. Cecil Beaton. Imperial War Museum. London. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library. Art in the Christian Tradition.

6. Dead Syrian Child, Turkish beach. Google photo.