The intersection of science and religion is a frequent topic on this blog. The relationship between these regions of human life are both more and less troubling than what we suppose.

First, they are much less troubling than what we might suppose because there is an immense space of complex intellectual dialogue between science and religion. Second, they are much more troubling than we might suppose because certain strains of scientific-based belief have their own superstitions such as crazy creation myths and erroneously canonized martyrs like Hypatia. Finally, there is a zone of ambivalence, such as the historical fact that the words science and religion, and what we assign to them as their proper roles in real life, are a very recent creations–the ancients and medievals knew them not.

One of the scholars responsible for mapping the interaction between these two, not necessarily separate, zones of science and religion is Ronald Numbers. His essay collection Galileo Goes to Jail and Other Myths About Science and Religion is one of the standard texts I recommend to my readers in my (nearly) exhaustive list of books on what science and religion are saying to each other these days.

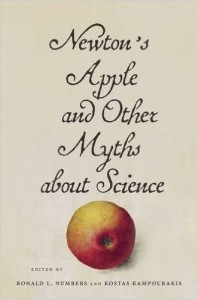

It was a pleasant surprise to discover Numbers has a new essay collection, Newton’s Apple and Other Myths About Science, while I was leafing through the Harvard University Press catalog yesterday.

I never suspected the apple story might be a fabrication since public school teachers mindlessly drilled it into my mind every chance they had:

A falling apple inspired Isaac Newton’s insight into the law of gravity―or so the story goes. Is it true? Perhaps not. But the more intriguing question is why such stories endure as explanations of how science happens. Newton’s Apple and Other Myths about Science brushes away popular misconceptions to provide a clearer picture of great scientific breakthroughs from ancient times to the present.

The apple is not the only science fairy tale we generally believe because authorities tell us to believe them:

Among the myths refuted in this volume is the idea that no science was done in the Dark Ages, that alchemy and astrology were purely superstitious pursuits, that fear of public reaction alone led Darwin to delay publishing his theory of evolution, and that Gregor Mendel was far ahead of his time as a pioneer of genetics. Several twentieth-century myths about particle physics, Einstein’s theory of relativity, and more are discredited here as well. In addition, a number of broad generalizations about science go under the microscope of history: the notion that religion impeded science, that scientists typically adhere to a codified “scientific method,” and that a bright line can be drawn between legitimate science and pseudoscience.

Who knew general knowledge is poisoned by so much superstition?

Then again, most of us aren’t aware that we are going through a Second Scientific Revolution, or what its consequences might be for theology.

Science also likes its myths nice and sweet. Have a nice day. Sorry for breaking your deeply cherished myths:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UXE1C–WezUWhile you’re at it read more about the Second Scientific Revolution‘s promise for theology, or look through a whole library of the finest books on science and religion.

Please be great and donate (through the PayPal button on my homepage). I’m walking an financial tightrope because rent time is here.