What will we call “PFG”? N.T. Wright’s magisterial, academic 2-volume study of Paul called Paul and the Faithfulness of God, volume 4 in his series called Christian Origins and the Question of God. I’ve got a PDF of Tom’s ground-breaking work and we’ll be discussing it until at least SBL in late November. So join along.

What will we call “PFG”? N.T. Wright’s magisterial, academic 2-volume study of Paul called Paul and the Faithfulness of God, volume 4 in his series called Christian Origins and the Question of God. I’ve got a PDF of Tom’s ground-breaking work and we’ll be discussing it until at least SBL in late November. So join along.

I begin with this: In my lifetime only a few books have been like this one (set). I consider EP Sanders’ Paul and Palestinian Judaism, Martin Hengel’s Judaism and Hellenism to be two rivals, with Jimmy Dunn’s Paul the Apostle a close third. This book rivals and may excel the others, so I want you to understand that we will be examining a book that will undoubtedly shape conversations for at least a decade and will influence discussions for decades.

Which of NT Wright’s book is most influential? your favorite?

Where will be going? Beyond what most have called Paul’s theology or NT theology or NT history, and behind much of what is called both. Here’s how Tom puts it:

Here we may note one particular result of this proposal. Most works on ‘Pauline theology’ have made soteriology, including justification, central. So, in a sense, does this one. But in the Jewish context ‘soteriology’ is firmly located within the understanding of the people of God. God calls Abraham’s family, and rescues them from Egypt. That is how the story works, and that is the story Paul sees being reworked around Jesus and the spirit. This explains why chapter 10, on ‘election’, is what it is, and why it is the longest in the book. I hasten to add, as readers of that chapter will discover, that this does not (as some have suggested) collapse soteriology into ecclesiology. Rather, it pays attention to the Jewish belief which Paul himself firmly endorses, that God’s solution to the plight of the world begins with the call of Abraham. Nor does this mean that ‘the people of God’ are defined, smugly as it were, simply as the beneficiaries of salvation. The point of the Jewish vocation as Paul understood it was that they were to be the bearers of salvation to the rest of the world. That, in turn, lies at the heart of his own vocation, issuing in his own characteristic praxis.

Tom sent some of this ms about four years ago when he was on sabbatical at Princeton and at the time there was not yet an introduction. So the ms began right where it begins now (without that Intro), in a most surprising place, with Philemon. That little letter often ignored. But Wright opens up with a letter from Pliny the Younger writing to a friend about a runaway freedman and then Wright compares that letter with Paul’s letter to a friend, Philemon, about his “wandering” (not quite runaway) slave who had become a Christian while Paul, of all places, was in prison in Ephesus … all to show that instead of hierarchy and power and benevolence we’ve got brotherhood and family and love and forgiveness. In other words, a “world apart” (6).

Instead of a fugitive Onesimus is a brother and Paul’s own son. In those terms we see the heart of the Pauline experiment of grace flowing in all directions. Paul’s word is “fellowship”: he is creating a new family, or God is creating a new family, that includes people from all tribes and nationalities and statuses. Gone, then, is the power hierarchy so typical of Rome.

Wright has a wrinkle on “for ever,” where he sees a possible looking back to the Pentateuch in which a slave could choose to be a slave forever by refusing manumission. Wright then suggests Onesimus will say Please let me back and I will serve you forever. And then v. 21 might suggest manumission as the far reach of what Philemon can do.

Classic paragraph from Tom Wright:

These discussions about the actual situation and the request Paul made have tended, as I said, to make exegetes overlook the point which is just as important in its way as the question of what Paul was asking for, namely the argument he uses to back up this central appeal. In order to make his triple (and increasingly cautious) request, Paul adopts a strategy so striking in its social and cultural implications, so powerful in its rhetorical appeal, and so obviously theologically grounded, that despite the chorus of dismis- sive voices ancient and modern the letter can hold up its head, like Reepi- cheep the Mouse beside the talking bears and elephants, alongside its senior but not theologically superior cousins, Romans, Galatians and the rest (16).

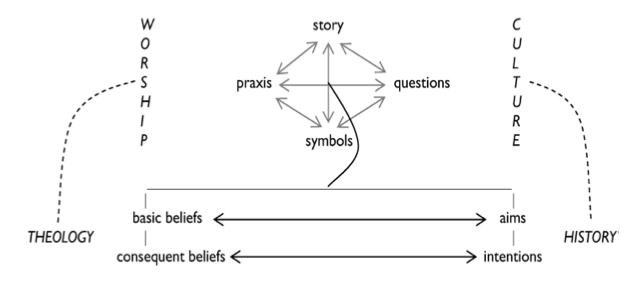

What we have then is a radical revisioning the monotheism and power on the basis of the cross and resurrection’s power to create one new body in Christ. It’s all about learning to think through this thing called “worldview”, as Tom says it:

What we have then is a radical revisioning the monotheism and power on the basis of the cross and resurrection’s power to create one new body in Christ. It’s all about learning to think through this thing called “worldview”, as Tom says it:

In particular, this way of approaching the matter explains why the tendency since at least medieval times in the western church to organize Paul’s concepts around his vision of ‘salvation’ in particular has distorted the larger picture, has marginalized elements which were central and vital to him, and – because this ‘salvation’ has often been understood in a dualistic, even Platonic, fashion – has encouraged a mode of study in which Paul and his soteriology is seen in splendid isolation from his historical context. Paul experienced ‘salvation’ on the road to Damascus, people suppose; his whole system of thought grew from that point; so we do not need to consider how he relates to the worlds of Israel, Greece or Rome! How very convenient. And how very untrue. If we take that route, a supposed ‘Pauline soteriology’ will swell to a distended size and, like an oversized airline traveller, end up sitting not only in its own seat but in those on either side as well. In particular, it will become dangerously self-referential: the way to be saved is by believing, but the main theological point Paul taught was soteriology, so the way to be saved is by believing in Pauline soteriology (‘justification by faith’). For Paul, that would be a reductio ad absurdum. The way to be saved is not by believing that one is saved. In Paul’s view, the way to be saved is by believing in Jesus as the crucified and risen lord. …

The hypothesis I offer in this book is that we can find just such a vantage- point when we begin by assuming that Paul remained a deeply Jewish theologian who had rethought and reworked every aspect of his native Jewish theology in the light of the Messiah and the spirit, resulting in his own vocational self-understanding as the apostle to the pagans.

Tom will be using the story of Philemon throughout PFG so it might be good to read it again, at least the core parts in Philemon 8-22:

Philem. 8 For this reason, though I am bold enough in Christ to command you to do your duty, 9 yet I would rather appeal to you on the basis of love—and I, Paul, do this as an old man, and now also as a prisoner of Christ Jesus. 10 I am appealing to you for my child, Onesimus, whose father I have become during my imprisonment. 11 Formerly he was useless to you, but now he is indeed useful both to you and to me. 12 I am sending him, that is, my own heart, back to you. 13 I wanted to keep him with me, so that he might be of service to me in your place during my imprisonment for the gospel; 14 but I preferred to do nothing without your consent, in order that your good deed might be voluntary and not something forced. 15 Perhaps this is the reason he was separated from you for a while, so that you might have him back forever, 16 no longer as a slave but more than a slave, a beloved brother—especially to me but how much more to you, both in the flesh and in the Lord.

Philem. 17 So if you consider me your partner, welcome him as you would welcome me. 18 If he has wronged you in any way, or owes you anything, charge that to my account. 19 I, Paul, am writing this with my own hand: I will repay it. I say nothing about your owing me even your own self. 20 Yes, brother, let me have this benefit from you in the Lord! Refresh my heart in Christ. 21 Confident of your obedience, I am writing to you, knowing that you will do even more than I say.

Philem. 22 One thing more—prepare a guest room for me, for I am hoping through your prayers to be restored to you.

Here is the outline to PFG, and those numbers are page numbers (so, Yes, this is a big double volume).

BOOK I

Contents: Parts I and II xi Preface xv

Part I PAUL AND HIS WORLD

- 1 Return of the Runaway? 3

- 2 Like Birds Hovering Overhead:the Faithfulness of the God of Israel 75

- 3 Athene and Her Owl: the Wisdom of the Greeks 197

- 4 A Cock for Asclepius: ‘Religion’ and ‘Culture’ in Paul’s World 246

- 5 The Eagle Has Landed: Rome and the Challenge of Empire 279

Part II THE MINDSET OF THE APOSTLE

- 6 A Bird in the Hand? The Symbolic Praxis of Paul’s World 351

- 7 The Plot, the Plan and the Storied Worldview 456

- 8 Five Signposts to the Apostolic Mindset 538

Bibliography for Parts I and II 572

BOOK II

Contents: Parts III and IV ix

Part III PAUL’S THEOLOGY

Introduction to Part III 609

- 9 The One God of Israel, Freshly Revealed 619

- 10 The People of God, Freshly Reworked 774

- 11 God’s Future for the World, Freshly Imagined 1043

Part IV PAUL IN HISTORY

Introduction to Part IV 1269

- 12 The Lion and the Eagle: Paul in Caesar’s Empire 1271

- 13 A Different Sacrifice: Paul and ‘Religion’ 1320

- 14 The Foolishness of God: Paul among the Philosophers 1354

- 15 To Know the Place for the First Time:Paul and His Jewish Context 1408

- 16 Signs of the New Creation: Paul’s Aims and Achievements 1473