If you’re anything like me, you have spent the last week and more in a slow boil as you’ve listened to reports of new anti-abortion legislation passed in Georgia, Alabama, and Missouri, among others. I’ve written about these bills several times, pointing, among other things, to a conflict between arguing that embryos and fetuses are legal people worthy of rights, and exemptions for rape and incest. But I’ve noticed a number of other things as well, and I want to take a moment to point to them.

First, this article. “Last month, my husband and I signed forms donating an embryo we had conceived to medical research,” the author explains.

In Pennsylvania (where my fertility clinic is located), a woman seeking an abortion must receive state-directed counseling designed to discourage her from the procedure. She must then wait at least 24 hours until she can continue. In other states, women are forced to undergo unnecessary and invasive ultrasounds, watch or listen to a description of the ultrasound, and hear a lecture on how the embryo or fetus is a human life. Clinics in some states must provide them with medically inaccurate information on the risks of abortion. After all that, women often cannot have an abortion without waiting an additional one to three days, depending on the state.

In contrast, all my husband and I had to do was sign a form. Our competence to choose the outcome of our embryo was never questioned. There were no mandatory lectures on gestation, no requirement that I be explicitly told that personhood begins at conception or that I view a picture of a day-five embryo. There was no compulsory waiting period for me to reconsider my decision. In fact, no state imposes these restrictions — so common for abortion patients — on patients with frozen embryos.

When I sent this article to a likeminded friend, she responded by noting that she does know people who are anti-abortion who do care about embryos. I know what she’s talking about—parents of so-called “snowflake” babies, frozen embryos who are “adopted”—implanted in a uterus and carried to term. And true enough, it would be an understatement to say that embryonic stem cell research has been controversial.

But still. There’s something to this.

It turns out that Georgia’s abortion bill last week deliberately excluded frozen embryos when it defined personhood, while including embryos in the womb—the bill determined personhood (and the full legal rights that entails) not based on unique DNA or developmental stage, but on location.

Have a look at this:

‘Natural person’ means any human being including an unborn child.

And then this:

‘Unborn child’ means a member of the species Homo sapiens at any stage of development who is carried in the womb.

Note the words “who is carried in the womb.” Per Georgia law, as it now stands, an embryo in a womb is a natural person with all of the legal rights of any other natural person; an embryo in a petri dish is not. Note, too, that the dividing line is not implantation. It is simply being in the womb.

In Georgia, an embryo inside a woman’s body is a legal person. An identical embryo in a petri dish is not.

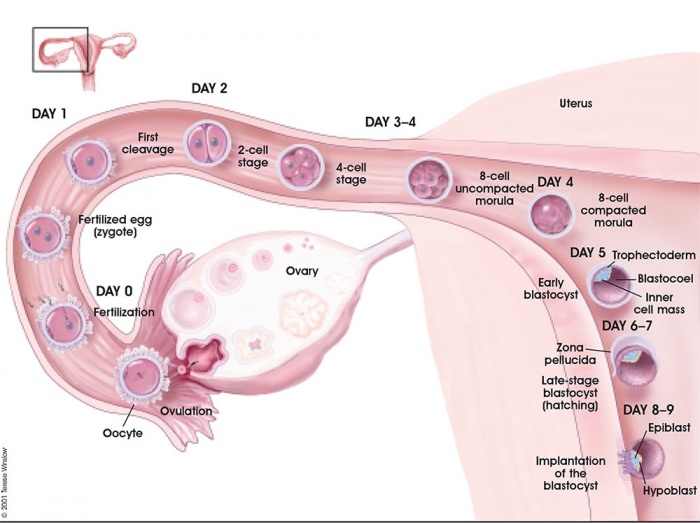

This calls for a quick look at embryonic development.

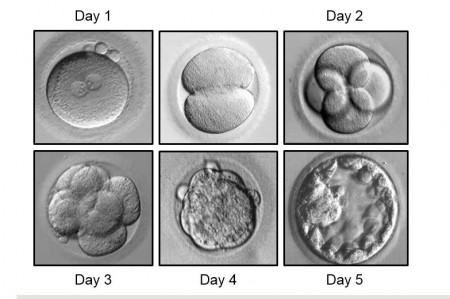

Three days after fertilization—the moment the embryo and sperm meet—an embryo consists of eight cells. It is generally around this time, for women using In Vitro Fertilization, that the embryo is inserted into the womb, although in some cases doctors may wait until the fifth day after fertilization to insert the embryo (at which point it is called a blastocyst).

What is an embryo conceived naturally doing three (or five) days after fertilization? Good question. Let’s take a look.

Before looking at the above chart, I had wondered idly if the issue might be implantation. Maybe, I thought, the embryo is only considered a legal person if it has implanted in the womb, something an embryo in a petri dish by definition has not done. But the fact that an embryo takes over full week to make it from fertilization to implantation suggests that this is not the case. After all, the bill defines an “unborn child” as a member of the species Homo sapiens “at any stage of development who is carried in the womb.” In other words, the defining factor is whether it is inside a woman’s body.

In Georgia, an embryo at three days post-fertilization is classified as a natural human with full legal rights if it is floating around inside a woman’s body, but not if it is outside of a woman’s body in a fertility clinic. In each case the embryo is exactly the same. And yet, one embryo is a legal person and the other is not. I find that highly, highly odd.

I don’t particularly want anti-abortion activists regulating what fertility clinics are allowed to do with extra embryos. Some states already have concerning legal jurisprudence surrounding such embryos. But if conservatives truly believed that every embryo is a person with a soul, you’d think “snowflake” babies would be common, and not the rarity they are. You’d think people would be rushing to ban the destruction of embryos in fertility clinics. You’d think they’d be considered people too.

The second thing I want to note is this:

This shouldn’t come as a surprise, since it’s a relationship that’s been known for years, but the states with the harshest restrictions on abortions also have the worst infant mortality rates.

The correspondence is unmistakable, and not hard to explain: Those states’ governments also show the least concern for maternal and infant health in general, as represented by public policies.

Are these states rushing to determine the cause of their disproportionately high maternal and infant mortality rates? Are “pro-life” activists demanding a solution? No. No, they are not.

There is something deeper going on here, though. If every abortion-minded woman carried her pregnancy to term, you’d have 25% more babies born each year than there currently are. Do conservatives actually think our country is “full”? That’s around a million more people, each year. There are just over 10 million undocumented immigrants in the U.S. Without abortion, we would add that many more people to the U.S. each decade. So, which is it? Are we full, or do we actually have lots of room for millions more people?

Also, 25% more women giving birth means we’d need more maternity wards—and more obstetricians, more pediatricians, more daycares, more schools, and so forth. We have absolutely had times in our history when more children were born (as a percentage) than are born today; I support fully funding these services to support whatever juvenile population we have. But do Republicans? Red states were those most loathe to adopt the medicaid expansion. Their schools are underfunded; rural hospitals are shutting down; the states banning abortion have some of the highest maternal mortality rates in the U.S.

This is why some pro-choice activists have argued that those opposed to abortion access should be called not “pro-life” but “pro-forced-birth.” If these states had a truly pro-life ethic, they would have excellent healthcare, especially low infant and maternal mortality rates, well-funded schools, and robust social programs. But they don’t.

I identified as solidly pro-life up until my junior year of college. I was passionate; I truly believed that abortion involved murdering babies.

And yet, if you’d asked me whether I’d save a crying three-year-old or a dish of embryos from a burning building, I would probably have struggled to answer. I would say embryos were people—I believed that life began at conception—but there was still a disconnect in terms of how the practical implications felt.

I was also very, very against anything that smacked of socialism. Women shouldn’t have sex if they couldn’t afford to have a child, I would have told you. Or, perhaps, I would have pointed to adoption as a solution for women who couldn’t afford to raise children. I would not have realized how heartless this sounded.

The problem was that for me, at the time, rules mattered more than people.

I have a Patreon! Please support my writing!