Oh, no! Not again? Yes, again. Another law enforcement officer shooting and the killing of an unarmed black person. This one happened at 2:15 pm, Saturday, January 8, 2022, in Fayetteville, North Carolina. Off duty Cumberland County Sheriff deputy Lt. Jeffrey Hash put to death Jason Walker, age 37. Whether Hash hit Walker with his truck or Walker jumped on to Hash’s hood and windshield is yet to be discerned. Witnesses are not agreed on what happened. Regardless, Walker suffered the death penalty.

Oh, no! Not again? Yes, again. Another law enforcement officer shooting and the killing of an unarmed black person. This one happened at 2:15 pm, Saturday, January 8, 2022, in Fayetteville, North Carolina. Off duty Cumberland County Sheriff deputy Lt. Jeffrey Hash put to death Jason Walker, age 37. Whether Hash hit Walker with his truck or Walker jumped on to Hash’s hood and windshield is yet to be discerned. Witnesses are not agreed on what happened. Regardless, Walker suffered the death penalty.

Black Lives Matter protests broke out the next day and continue as I write this column post. When will American society end this unending cycle of shooting, death, and protest? Who will tell the narrative that will lead us to the next stage of civil order and harmony? Can the church become a change agent?

Here is the question we asked in Part 1 of “A Progressive Race Narrative“: Why is it that America, like a family car stuck in a Minnesota snow, only spins its wheels on matters of race? I tender an answer. Because of the absence of a progressive race narrative–or worldview–with the traction that could move the society forward toward a healthy democracy?[1] (Art: Jesus with Children by John Lautermilch)

What is the problem? The problem is that our progressive friends have not to date provided the kind of narrative or worldview that unites rather than divides. We spin in disorientation. We’re hit from two directions. First, we’re thunder struck by the sheer diversity of competing narratives, none of which is compelling. The second direction is our disappointment that the existing progressive race narrative is incomplete. It lacks a future vision. It produces hopelessness. Let me explain.

The Current Dominant Race Narratives

The two dominant narratives are proffered by the scolders and the deniers. According to the scolders, America is helplessly racist because white supremacy is universal, innate, and intractable. According to the deniers, this history is not as bad as the scolders say. And, furthermore, our political and institutional leaders are not racist. The scolders accuse the deniers of hypocrisy and deceit and demand the equivalent of confession and repentance. That’s as far as we can get.

Yes, other narratives are also-rans. How about the Neo-Nazis? Neo-Nazis seek to employ their ideology to promote hatred and white supremacy, attack racial and ethnic minorities (which include antisemitism and Islamophobia), and in some cases to create a fascist state.

Short of overt Nazism, how does the more subtle white supremacy narrative work? This narrative does not refer to the self-conscious racism of white supremacist hate groups. Rather, according to an Atlantic article, it refers “a political, economic and cultural system in which whites overwhelmingly control power and material resources, conscious and unconscious ideas of white superiority and entitlement are widespread, and relations of white dominance and non-white subordination are daily reenacted across a broad array of institutions and social settings.”

How about this tortuous and diversionary debate over Critical Race Theory (CRT)?

What is the perspective of American family members living in Asian or Hispanic or Arab or Amerindian or Asian Indian communities? Do they simply watch the white forces and black forces duke it out, relying solely on a just legal system to protect them? Who can we trust to maintain a just legal system?

These are the also-rans. The dominant narratives are those of the scolders and deniers.

Scolders versus Deniers

For the discussion that follows, let me focus on the scolders and the deniers. Why? Because their narratives dominate the acceptable self-interpretations of today’s Americans. Like piranha fish in a frenzy, the scolders and deniers eat up the narratives of the Neo-Nazis and white supremacists.

![]() The frenzied question of race is one of the most urgent on the public theologian’s agenda. In our series on public theology, we have tried to clarify the confusion over Critical Race Theory in contemporary discourse. We’ve appealed to God’s identification with us in the incarnation as a divine conferral of dignity on each of us, regardless of race.

The frenzied question of race is one of the most urgent on the public theologian’s agenda. In our series on public theology, we have tried to clarify the confusion over Critical Race Theory in contemporary discourse. We’ve appealed to God’s identification with us in the incarnation as a divine conferral of dignity on each of us, regardless of race.

Can we construct a progressive race narrative? In this Patheos column post, I will ask the public theologian to tender to American society the value of confession, repentance, and reconciliation. What needs confession on the part of the white populace is complicity in racial prejudice and institutional racism. To wake us to the need for confession, we could retrieve that version of history that includes the full story of injustice based on race.

Confession then leads to repentance and renewal guided by a colorblind vision of a universal human race. Such a vision of reconciliation and renewal might provide the traction the progressive Christian needs to get the vehicle of transformation moving again. Are we ready to construct a narrative or worldview that generates hope for the future?

What terms might be best to introduce into public discourse? Try: Recognition, Redirection, and Renewal.

Sidebar: Distinguishing Prejudice and Racism

Part of the answer to the question–why does America spin its wheels on the matter of race?–is located in the confusion between prejudice and racism. A quarter century ago we could understand prejudice as Caleb Rosato did.

Prejudice is an inflexible, rational attitude that, often in a disguised manner, defends privilege, and even after evidence to the contrary will not change, so that the post-judgment is the same as the prejudgment.. In the definition of prejudice, the indictment is greater for post-judgment than for pre-judgment. If you don’t have post-judgment in your definition of prejudice you don’t know what you are talking about. This is because racial prejudice is the refusal to change one’s attitude even after evidence to the contrary, so that one will continue to post-judge people the same way one pre-judged them.

I insist that we return to the Civil Rights Movement to retrieve the distinction between prejudice and racism. Prejudice refers to bias held by individuals or cultural tropes that impute inferiority to racial or ethnic groups. Racism refers to the impact on nonwhite persons by policies or practices that are discriminatory. Prejudice is personal, whereas racism is impersonal. In institutions I have served I found leaders who were anti-prejudice yet still sponsored institutional racism along with sexism and ageism. Racism can exist without racists, sociologists contend. I weep that current discourse blurs this distinction, thereby preventing accurate analysis of our situation.

Oh yes, I recognize that the theory of aversive racism draws our attention to “individuals who are presumed to be consciously egalitarian yet unconsciously prejudiced.” But I must ask critically: is this a theory that assumes at the outset that all white individuals are prejudiced in either conscious or unconscious form?

Oh yes, I recognize that the theory of aversive racism draws our attention to “individuals who are presumed to be consciously egalitarian yet unconsciously prejudiced.” But I must ask critically: is this a theory that assumes at the outset that all white individuals are prejudiced in either conscious or unconscious form?

This is the problem we see in the current progressive race narrative. If we work with the assumption that no individual can transcend racial prejudice, then there is no hope for overcoming individual prejudice let alone institutional racism. Institutional racism can be redirected if and only if individuals beyond prejudice will it to happen. Fatalistic theories themselves can have a repressive impact. (Art: Jesus with children by Arthur Robins)

To define racism as power plus prejudice, which is common, is misleading. Again, we can find institutions which practice racism even though those who work in those institutions are not prejudiced. This needs to be accounted for.

The Hopelessness of Today’s Progressive Narrative

“Teaching about systemic racism and white supremacy can educate white people about why Black people and other people of color experience racism.” So contends Rann Miller in his article, “Teaching Critical Race Theory is about Liberating All of Us,” in The Progressive Magazine. I happen to endorse what Miller says here. However, not all is quiet on the racial front. It’s much more complicated.

The narrative our favorite progressives currently tell us is that beginning with 1619 the continent fell into a racist crevasse and has been cragfast on injustice ever since. As if it were in the nation’s DNA, prejudice and racial discrimination are inherited traits that cannot be washed away with political soap and economic water. The fates have condemned America to a destiny of white supremacy, bigotry, and cruelty. This is a narrative without hope.

The public theologian of the Augustinian tradition will be quick to point out an additional problem, namely, the gnostic fallacy. It is a fallacy to think that educating us in true history will in itself produce social change. Theological anthropology teaches us something both relevant and important. The fundamental human problem is not properly diagnosed as ignorance. Rather, the fundamental human disease is a sickness of the will. One can have knowledge, yet still will prejudice, discrimination, and violence. One can be exposed to the light, yet still choose darkness. What does this suggest? In addition to recognition by teaching revised history, we need the present generation to repent and redirect.

Theological anthropology comports with the social science of a generation ago. A 1995 article in the American Psychologist by Caleb Cosato concludes: “racism is not a universal feature of human psychology but a historically developed process.” If prejudice and racism are historical, they are subject to reform. There is hope here.

Scolders versus Deniers Again

Two irreconcilable reactions to this narrative have fissured social consciousness into scolders and deniers. In the name of racial justice, the scolders rebuke white supremacy and denounce institutional racism. With undisguised glee, progressives prophesy the coming of new American minority, the white race. This triggers anxiety, and anxiety should sound a siren in the public theologian’s ears.

Scolding, at least to date, has failed to convert very many white supremacists to Black Lives Matter. The most common reaction to scolding is denial. Denial comes in two forms: innocent puzzlement and self-justifying deceit. The photo gone viral—a six year old white girl holding up a protest sign reading, “I am not an oppressor”—points to puzzlement. Since the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s, an enormous swath of America’s European descendants have eschewed racial prejudice and now vigorously support equality. These deniers are puzzled that their progressive friends have locked them into a prison of racial oppression without a key for self-extrication.

Scolding, at least to date, has failed to convert very many white supremacists to Black Lives Matter. The most common reaction to scolding is denial. Denial comes in two forms: innocent puzzlement and self-justifying deceit. The photo gone viral—a six year old white girl holding up a protest sign reading, “I am not an oppressor”—points to puzzlement. Since the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s, an enormous swath of America’s European descendants have eschewed racial prejudice and now vigorously support equality. These deniers are puzzled that their progressive friends have locked them into a prison of racial oppression without a key for self-extrication.

Also among the deniers are influencers in media and politics who pervert the semi-invisible structures of institutional racism into a disguised ideology that supports white supremacy. Fear that racial domination may be slipping away has prompted renewed support for Neo-Naziism. Anxiety that uncontrollable change is about to engulf the culture has energized racial politics in the wake of the first presidency of an African American, Barack Obama (2009-2017).

The Pastoral Task of the Public Theologian

The pastoral task of the public theologian is to perceive and bring to articulation existential anxiety. A Harvard study, “Whites See Racism as a Zero Sum Game That They Are Losing,” identifies one sector of anxiety.

Although some have heralded recent political and cultural developments as signaling the arrival of a postracial era in America, several legal and social controversies regarding ‘‘reverse racism’’ highlight Whites’ increasing concern about anti-White bias. We show that this emerging belief reflects Whites’ view of racism as a zero-sum game, such that decreases in perceived bias against Blacks over the past six decades are associated with increases in perceived bias against Whites—a relationship not observed in Blacks’ perceptions. Moreover, these changes in Whites’ conceptions of racism are extreme enough that Whites have now come to view anti-White bias as a bigger societal problem than anti-Black bias.

We normally respond to anxiety by striking out with violence. And, of course, we justify this violence by declaring ourselves to be the victim. In this case, the whites surveyed declare themselves victims of “anti-White bias.” As we’ve seen in my previous treatments of sin as scapegoating, this anxious situation is rife for division, deceit, and danger. The first pastoral task is this: address the anxiety. Nothing in the current progressive agenda addresses this anxiety. Denial should not be unexpected.

How does denial manifest itself? In order avoid overt prejudice, code language is blown like a dog whistle. In code we hear, “violence on many sides, many sides.” We hear “No CRT in our Schools?!” or erect a “wall” to wall out Central American immigrants. What these oblique slogans actually say is this, “Make America White Again.”

The public theologian should be grateful that the white supremacists among us lie about themselves. The Neo-Nazis don’t, to be sure. But, our political leaders and divisive media outlets affirm racial justice while promoting restrictions on voting rights for African Americans. This is hypocrisy. But, I believe hypocrisy is better than honest Neo-Nazism. When the values of racial justice are touted de rigor, we keep before us the standard to which we strive to conform our actual society.

There is at present no progressive narrative one can listen to or repeat that envisions a bridge over the fissure let alone a future confluence of separate streams into a single flow. To be clear, the fissure is not between people of African descent and those of European descent. No. Rather, this fissure results from our incapacity to respond confidently and creatively to the new progressive narrative of hopelessness.

Discourse Clarification and Worldview Construction?

“Race is…illusion, fiction, modern social construction.” writes Roman Catholic theologian Shawn Copeland[2] If race is a delusion, then Christians have no business supporting the delusion either within the church or in the wider culture. Rather, the public theologian brings truth to culture, even if this truth requires confession. Patheos columnist John O’Keefe explains why white persons especially need to confess.

If we truly face those demons, those demons of hate, those demons of racism, we can start moving forward. If we are unable to address our individual racism, we will never move past racism as a culture. You see, for the culture to change, individuals need to address the internal demon of racism.

For the sake of this democracy’s future, might the public theologian offer something of value to the wider discourse? Might the Cristian triad of confession, repentance, and reconciliation placed under those spinning tires provide traction? What each of us needs is the open door for cleansing and renewal. This is what the traditional Christian dialectic of confession and pardon offered. This is absent in the current public discourse over race.

Here is the chief challenge set before the progressive narrative of hopelessness. It’s hopeless. It offers no gate that opens toward renewal. Even the term, ‘colorblind‘, has been canceled so that progressives cannot unlock their cells with it. Accordingly, this term can only mean the ignoring or denying of the specific black experience of oppression. Closed off is the value of this term as an ideal, as a promise. The colorblind white person is now indistinguishable from the slave holder or KKK firebrand. By locking all white persons into an inescapable cell of racist guilt, it throws away the key.

Is there a key to worldview construction that unlocks hope? Yes. When in Christian history a person would be laden by sin with guilt and shame, the key that could open the gate to renewal was confession, absolution, repentance, and reconciliation. Confession of sin—in this case the sin is cultural prejudice and racist institutions produced by covert and overt white supremacy—is just what our current progressives are asking for.

Let’s embrace this confession. Let’s revise our history as accurately as possible in light of this willingness of the present generation to face the reality of America’s history. Once Americans have confessed this history, it will be time to repent.

Learning from South Africa

Repentance from racism was forceful in 1985 when the Kairos theologians challenged the so-called “state theology” of the government in South Africa. The sin in that instance was known as, “Apartheid.” In the South African Kairos Document we read: “What this means in practice is that no reconciliation, no forgiveness and no negotiations are possible without repentance. The Biblical teaching on reconciliation and forgiveness makes it quite clear that nobody can be forgiven and reconciled with God unless he or she repents of their sins.” The Kairos theologians were public theologians engaged in public discourse clarification. They introduced repentance into the government’s vocabulary. Might this word, ‘repentance’, strengthen today’s progressive narrative?

Beyond repentance would come reconciliation. Under the leadership of Nelson Mandela, Tshenuwani Simon Farisani, the now late Desmond Tutu, and other African National Congress leaders, this term, ‘reconciliation’, provided a guiding light for post-Apartheid South Africa to emerge from its darkness. Might reconciliation provide a guiding light in today’s American situation?

Beyond repentance would come reconciliation. Under the leadership of Nelson Mandela, Tshenuwani Simon Farisani, the now late Desmond Tutu, and other African National Congress leaders, this term, ‘reconciliation’, provided a guiding light for post-Apartheid South Africa to emerge from its darkness. Might reconciliation provide a guiding light in today’s American situation?

The decisive requisite to reconciliation, of course, is truth. Objective history provides one level of truth. Confession and repentance provide a second level. We need both to reach the next level, reconciliation. Could American progressives flourish within this narrative that leads to reconciliation? (Heart photo from Keith Giles Patheos column where a black American, Kyle Butler writes, “Racism: My Answer To It.”)

The Problem of Language

In public discourse the term, colorblindness, has been disparaged for its hypocritical usage . It has been used to hide institutional racism. But, I believe it should be retrieved, cleaned, and polished. We need the concept of colorblindness in order to construct a vision of the future we want. Colorblindness or a similar term is necessary if we are to unlock the tiger now confined to the cage the progressive narrative has locked us into.

Now let’s turn to specifically theological language. Public hostility toward Christianity in America may be at an all time high right now. The younger generation—urged on by social media—is emptying church pews like passengers on the Titanic jumping overboard. The ecclesial ship is sinking, they allege, because of the church’s overemphasis on sin, its refusal to honor and welcome LGBTQ+ persons, its denial of evolution, and its alliance with the Republican Party. This is a misperception based on the assumption that only the evangelical tradition exists in America. Mainline Christian groups celebrate science and embrace human equality at all levels. Be that as it may, anti-Christian rhetoric on Facebook and other social media alerts us to additional social unrest. But, that’s another story.

For the sake of the world rather than the sake of the church, let me ask: should the public theologian seek vocabulary that might be less stained or tarnished with the gospel? Might terms such as confession, repentance, and reconciliation sink our ship even before departing the dock?

This needs to be thought through by the public theologian. Let me nominate a substitute rendering: recognition, redirection, and renewal. Within the category of recognition, we could include both an honest revision of America’s history accompanied by confession of shared or communal responsibility. Within the category of redirection, we could include the orientation of legislation and public policies that redress injustices and restructure our institutions. Within the category of renewal, we could energize those already existing cultural visions of a future single racially reconciled society.

Conclusion: Church as Change Agent

Are we ready and able to construct a progressive race narrative? In Part 1 I lifted up a vision for such a narrative in terms of near future, medium future, and long range future.

I recommend we construct a progressive race narrative out of existing materials–that is, out of selected values already alive in our culture. I recommend we lift up a vision of the near, medium, and long range futures.

First, in the near future we lay a foundation of recognition. This recognition revises America’s story to include an objective and realistic account of the role racial injustice has played in the course of events. It also includes confession of the sins perpetrated by white supremacism.

Second, for the medium range future, we redirect institutional policies to consciously embrace racial diversity, even cultural diversity. Affirmative Action programs in recent decades were largely effective, despite pockets of resentment. For the time being, affirmative policies could help redress imbalances that have led to institutional racism in mortgage finance, law enforcement, imprisonment, and corporate board rooms.

Third, renewal for the long range future is predicated on a colorblind vision of a single universal humanum. Yes, I’m aware that the term, colorblind, is controversial. Even so, nothing less than colorblindness is requisite for reconciliation, justice, and filial love.

This long range vision, like a rainbow, should include all colors. It’s a mistake to continually formulate the race question in binary fashion as either white versus black or white versus non-white. The American family includes adoptees from every clime and continent. There is plenty of welcome room in the renewed America for its white children, just not as patriarch of the family.

Let me close with the words of Valerie Miles Tribble, one of my Berkeley colleagues at the GTU. Dr. Tribble feels intensely both the urgency for change and the desperate need for change agents. “A change agent task, then, includes examining ways that racialized differences are manifested in the present cyclical crescendos of Black Lives Matter times. I approach the era … to offer an extended view of public events linking discrimination and hateful acts, and cited testimonies to the continued denial and silence that kills.”[3] By recognizing the truth and by repenting from the history of this truth, America just might redirect itself toward a vision of renewal through reconciliation.

—–

[1] The need for such a progressive narrative has been suggested by Noah Feldman of Harvard Law School. Feldman suggested this when appearing on the Fareed Zakaria television show, 12/26/2021.

[2] M. Shawn Copeland, “Body, Race, and Being,” in Constructive Theology: A Contemporary Approach to Classical Themes, ed. by Serene Jones and Paul Lakeland (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2005) 97-116: 98.[3] Valerie A. Miles-Tribble, Change Agent Church in Black Lives Matter Times (Lanham MD: Lexington, 2020) 17-18.

▓

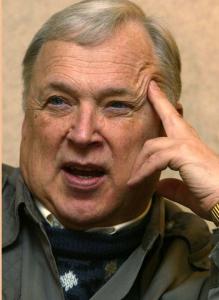

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his forthcoming, The Voice of Public Christian Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his forthcoming, The Voice of Public Christian Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

▓