Ecotheology when it’s “Time to Act”

PT 3001

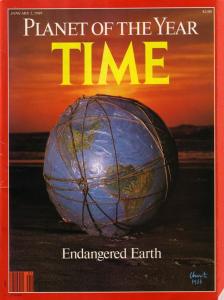

It’s time to act! Does the new climate deal in the U.S. Congress count as acting? Since the Jimmy Carter administration (1976-1980), Uncle Sam has been considering a rewrite of our nation’s will to bequeath future generations a planet denuded of its resources for supporting a flourishing human existence.

It’s time to act! Former Vice President Al Gore has been warning us for three decades that–if we do not recognize that it’s time to act–we will lose our planet’s capacity to sustain life as we know it. “Now is the time to act on climate change as the U.S. experiences record heat and wildfires rage across Europe.”

More. “They’re saying that if we don’t stop using our atmosphere as an open sewer, and if we don’t stop these heat trapping emissions, things are gonna get a lot worse,” Gore told ABC “This Week” co-anchor Jonathan Karl. “More people will be killed and the survival of our civilization is at stake.”

The politician Al Gore of the 1980s had learned from the scientists of the 1970s. And, Gore’s still learning. But the world is ignoring. Are our ecotheologians learning or ignoring? Certainly no ignoring by ecotheologian Cynthia Moe-Lobeda who has just launched an educational program for seminarians, the Center for Climate Justice and Faith, in Berkeley.

It’s “time to act,” today’s scientists tell us with an even stronger sense of urgency. It’s time to extinguish the fire before we all get burned up. Will our ecotheologians fight the fire?

Today’s scientists sound like Isaiah crying “woe” to ancient Judah. “Woe to the sinful nation, a people whose guilt is great” (Isaiah 1:4). It’s time to repent. It’s time to take right action.

Science (June 24, 2022): It’s “Time to Act”

The June 24, 2022 issue of Science carries a “Special Section” (pages 1393-1426). It’s a set of informative articles that challenge us with both warning and opportunity. These studies take up biofuels, food systems, clean technologies, and the need for economic reform. Here’s the message: it’s time to act on behalf of a planet in peril.

“Climate scientists have known and warned for decades that our activities are leading to dangerous climate change, the effects of which we are experiencing now. Technologies for alternative energy sources have also existed for decades, yet political and financial interests have prevented their widespread uptake, as well as transformational economic and social change needed to end our alteration of climate.” (Ash, et al. 2022)

Note that our scientists have been prophetically warning us for decades—since the 1960s and especially the 1970s—to listen to the agonized cries from our planet. Some religious leaders, educators, and those holding political office such as Jimmy Carter and Al Gore have heard the cries and sought transformational healing. But, short-sighted economic systems combined with political recalcitrance have perpetuated the bad habits that contribute to global warming, climate change, pollution, and our planet’s loss of fecundity. “We have had the science and technology to deal with ecological problems for years,” observes queer theologian Whitney Bauman; “yet these problems just keep getting worse” (Bauman, 2018, p. 96).

The Scientist as Futurist and as Prophet

In what follows I would like to wax on two overlapping points. First, today’s climate change/global warming scientists maintain the tradition of their predecessor futurists. A half century ago, ecologists were called, “futurists.” Using newfangled computers among other tools, scientists invoked what I’ve called the u-d-c formula: understanding, decision, and control. Our empirically based understanding of trends is forcing us to make a decision, a moral decision of global consequence. The right decision will give us control over our destiny. The wrong decision or no decision means loss of control. No decision will lead to our demise as a species. That’s the futurists’ warning we’ve been hearing since your grandparents began driving their first V-8.

In what follows I would like to wax on two overlapping points. First, today’s climate change/global warming scientists maintain the tradition of their predecessor futurists. A half century ago, ecologists were called, “futurists.” Using newfangled computers among other tools, scientists invoked what I’ve called the u-d-c formula: understanding, decision, and control. Our empirically based understanding of trends is forcing us to make a decision, a moral decision of global consequence. The right decision will give us control over our destiny. The wrong decision or no decision means loss of control. No decision will lead to our demise as a species. That’s the futurists’ warning we’ve been hearing since your grandparents began driving their first V-8.

Second, I’d like to show how today’s ecotheologian should treat the scientific community as a divinely appointed prophet. This does not imply that each scientist is a virtuous or holy person, to be sure. But, we need to thank God that scientists for three quarters of a century now have been paving the path that our society needs to follow to get to safety, wellbeing, and flourishing.

Is it the Time to Act?

Note again the theme in the Science treatment of ecology, “Time to Act.” What the scientist does is provide the empirical data regarding trends in nature such as pollution distribution or species extinction. This is what I call, “understanding.” The scientist then makes a forecast—not a prediction exactly—of what will transpire if these trends continue. Frequently, these identified trends are leading to a disastrous deterioration of our ecosystem. This leads to the necessity of our planetary society to make a “decision” leading to action. Without a decision followed by remedial long-range action, we the human species will sacrifice our control over our own destiny. To gain control, we need a program with long term future effects vested in a vision of planetary flourishing.

Here is an example. Forest conservationist at the University of Utah, Nalini Nadkarni, outlines the futurist u-d-c method inherited by today’s ecologist. “One of the primary paradigms of ecology is to document the patterns that are manifested by organisms…figure out the processes that create those patterns…With knowledge of pattern and processes, ecologists can make predictions such as the future distribution of a species.” (Nadkarni 2017, 415). Note, Nadkarni uses the term, “prediction,” where futurists use the term, “forecast.” This is minor, however. What’s important is the u-d-c structure which turns science into morality.

Eco-Healing Action and Restorative Justice are Inseparable

The rich should help the poor. That was one conclusion of the Club of Rome in its 1972 study, The Limits to Growth. [1] Why? Poverty pollutes. That’s right. The uneven distribution of access to economic wellbeing belongs among the causes of ecological threat. If the wealthy are to survive, the poor in the developing world must advance to the middle class with access to life chances. The ethical implications of distributive justice if not restorative justice are integral to scientific forecasts, warnings, and challenges.[2]

On the one hand, population growth especially among the world’s poor needs to have limits. On the other hand, maldistribution of resources may be more decisive than the population growth itself. But, the two are connected. “The UN says world population will plateau at 10.9 billion by the end of the century. The other groups forecast earlier and smaller peaks” (Adam 2021, 463). Increased access to economic largess will indirectly limit population growth while contributing to the planet’s bio-balance.

Eco-justice is a profound concern voiced by economist Richard Norgaard, with whom I team-taught eco-ethics for a brief period at University of California, Berkeley. Norgaard has contributed significantly over the decades to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). According to Norgaard and his other colleagues, “climate change presents perhaps the most profound challenge ever to have confronted human social, political, and economic systems….The social problem solving mechanisms we currently possess were not designed, and have not evolved, to cope with anything like an interlinked set of problems of this severity, scale, and complexity. There are no precedents” (Dryzek, Norgaard and Schlosberg 2011, 3).

Injustice is sinful. So also is mistreatment of the planet. By employing terms such as “ecological sin, or eco-sin,” theologian Chris Doran is putting theological language to work here (Doran 2017, 100). Ethicist Cynthia Moe-Lobeda puts eco-ethics and the pursuit of justice together theologically. “I use structural sin and structural evil to signify theologically the same reality: structural injustice” (Moe-Lobeda 2013, 64).

Is there hope? Yes, says Methodist theologian and activist Sharon Delgado. That hope rises up from the symbols of cross and resurrection. Sharon’s new book, The Cross in the Midst of Creation: Following Jesus, Engaging the Powers, Transforming the World, asserts that the crucifixion is ongoing as institutional powers diminish human life and destroy creation. Further, the resurrection is ongoing as faith overcomes despair and the Spirit equips people to follow Jesus in the struggle for a transformed world.

What should be ecotheologian’s vision? Prompted by the symbols of the kingdom of God and new creation, our vision should lift up a worldview replete with a just, sustainable, participatory, and planetary society. Restorative justice is the bridge between the present and that envisioned future. Restorative justice begins with a vision of full participation in both the work and the reward of a just yet sustainable planetary economy.

Toward a Just, Sustainable, Participatory, and Planetary Society

How should the theologian, prompted by a scientific understanding of the ecological crisis, respond doctrinally and ethically? What comes to mind first are creation and anthropology. We’ll take up creation next. Right now, let’s simply observe that the theologian is prompted by the global scope of eco-science to reaffirm a single universal humanum, a single human race. Our familiar divisions into genders, races, ethnicities, nationalities, and such must be put on pause for a moment while we think holistically. Nothing less than the common good of the entire human race can count as the scope of ethical deliberation.

The ecotheologian must address a tension. On the one side, we find the public theologian demanding justice for the subaltern. On the other hand, we find the eccotheologian pressing for a single planetary society. Will justice get sacrificed for unity? No.

Theologian Catherine Keller confronts the challenge head on in the context of urgency.

“There isn’t time. At stake is the future of livable life for us all. The whole dysfunctional family. And in the meantime the most vulnerable among us, often women, will be thrown by droughts and meltings and fires, collapsing coastlines and islands, agricultures and cultures, into rapidly intensifying jeopardy…..It isn’t a matter of putting off our issues of gender and sex and race and ability, let alone class, but of colluding in the spirit of the grassroots movements and their dynamic entanglements. Then we can keep talking, arguing, contesting particular priorities…without delaying commitment to earth-keeping” (Keller, 2015, 183).

Local justice and planetary urgency: do these two fit for the ecotheologian? Yes.

Like a chef tending to each individual pan sizzling or boiling on the stove, queer theorist and eco-theologian Whitney Bauman has in mind the imminent serving of the whole meal. Despite his passionate concern for justice on behalf of marginalized local communities, he recognizes that all such communities belong to the planetary society as a whole. “Whereas globalization is about the imposition of sameness over the face of the planet, planetarity is about connecting bodies and places of the planet through their differences—in recognition that our difference is what constitutes our very identities and localities” (Bauman 2014, 115-116). I suggest that the term, participatory, integrates the flourishing of the individual and the local reciprocally with the flourishing of the planetary.

Ecotheological Re-Thinking of the Theology of Creation

Ecology is a matter of worldwide religious concern. Sockdoligers Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim provide an informative overview. See the sum of their quarter century work, “Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology” for a treasure chest of resources. Don’t miss Mary Evelyn’s “press kit” or John’s “press kit” for even more.

Theologians, both pagan and Christian, by and large approach creation and anthropology with the assumption that we must re-integrate human consciousness into the natural world. The theologian’s task, allegedly, is to de-anthropocentricize. Our task as a society is to realize more fully—even romantically—our embeddedness in nature. This approach seems to presume that if we moral human beings treat Planet Earth like our mother, then we will be more caring and responsible for Earth’s welfare.

Citing the Canticle of the Creatures by St. Francis of Assisi, Pope Francis opens Laudato Sí with…

“Praise be to you, my Lord, through our Sister, Mother Earth, who sustains and governs us, and who produces various fruit with coloured flowers and herbs”

In her laudatory analysis, Mary Evelyn Tucker observes how “the pope encourages us to see the human economy as a subsystem of nature’s economy, namely the dynamic interaction of life in systems” (Tucker 2015, 187).

Proleptic Creation and Retroactive Ontology

My own approach differs. Oh yes, Mary Evelyn Tucker and similar ecotheologians are right on target when folding human survival and flourishing into nature and into planetary sustainability. But, I add the dimension of the future. Planet Earth is itself dynamic. Planet Earth is itself folded into the future of our solar system, the Milky Way, and even the cosmos.

Sparing the details I attend to elsewhere—See: Ted Peters, “Can We Locate Our Origin in the Future? Archonic versus Epigenetic Creation Accounts” —I recognize that nature is epigenetic and historical. The present moment is ontologically open to the future. Nature and history are together open even to the future of God.

More. I recommend that our ecotheologians ally with systematic theologians to construct a retroactive ontology. The initial axiom for retroactive ontology is this: to be is to have a future. It is God who calls us into being by graciously offering us and our cosmos a future. New Testament symbols such as Isaiah’s Peaceable Kingdom, the Gospels’ kingdom of God, or St. Paul’s new creation, or the New Jerusalem of Revelation 21, prompt a vision of heaven in relation to Earth as God intends it. The harmony between nature, humanity, and God in the eschatological vision should be the eco-ethicist’s guide.

God’s future-giving comes in two forms. Negatively, God is releasing creatures such as you and me from the chains of our origin and from recent efficient causes each moment. Each moment God lays before us a finite set of potentials, possibilities that prompt us to deliberate, decide and take action. By taking action, we liberated free creatures play a creative role. We become one efficient cause among many in the history of creation. Our moral moment of crisis is ontologically grounded: it’s time to act.

The resulting ethic is a proleptic ethic. Beginning with a vision of the transformed future, the proleptic ethicist guides us toward making the future reality a present actuality. What remains, of course, is the will of our emerging planetary society to make the decision that leads to restorative action.

When Al Gore or our scientists emphasize that “it’s time to act,” we can rely upon God to release us from the inertia of past bad habits and open a future for new healthy habits and restorative justice.

Well, this is my approach. Be that as it may, I am grateful that God has raised up three generations of scientists who issue the prophetic warning: repent and resolve to take the action necessary to preserve if not enhance our planet’s fecundity. I am also grateful that God has raised up two generations of theologians who have heard the prophetic warning and respond with an inspiring vision of a just, sustainable, participatory, and planetary society.

Conclusion: It’s Time to Act

This article is one of my contributions to public theology. I believe public theological matters are conceived I the church, critically refined in the academy, and offered to the world for the sake of the global common good. In summary, this is what I have tried to offer.

For more than half a century God has bypassed the church to raise up scientific prophets to warn the world that ecological disaster is nigh. If the human race does not repent from its glutenous pillage of Planet Earth and commit to serving a common good that includes all creatures within our biosphere, disaster will befall us. It is now time for the public theologian to thank the prophets of alarm and offer faith’s resources to a global commitment to a just, sustainable, participatory, and planetary society oriented around the common good. The common good provides a middle axiom between faith in God’s eschatological promise that the lion will lie down with the lamb (Isaiah 11), on the one hand, and the urgent actions needed to return our natural world to its fecund life, on the other.

It’s time to act.

▓

Ted Peters pursues Public Theology at the intersection of science, religion, ethics, and public policy. Peters is an emeritus professor at the Graduate Theological Union, where he co-edits the journal, Theology and Science, on behalf of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, in Berkeley, California, USA. His book, God in Cosmic History, traces the rise of the Axial religions 2500 years ago. He previously authored Playing God? Genetic Determinism and Human Freedom? (Routledge, 2nd ed., 2002) as well as Science, Theology, and Ethics (Ashgate 2003). He is editor of AI and IA: Utopia or Extinction? (ATF 2019). Along with Arvin Gouw and Brian Patrick Green, he co-edited the new book, Religious Transhumanism and Its Critics hot off the press (Roman and Littlefield/Lexington, 2022). Soon he will publish The Voice of Christian Public Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

▓

[1] The Club of Rome gave us the term, world problematique. Now, we hope the term, ‘Climate Change’ or CC, will cover the entire complex network of destructive forces. CC does not affect only one’s own back yard or only one’s own country. “The essence of the emergent crisis of global warming is that we are importing enormous amounts of energy from the crust of the Earth and exporting entropy (that is, progressive disorder) into the previously stable, though dynamic, ecological systems upon which the continued flourishing of civilization depends,” writes former U.S. Vice President Al Gore (Gore 2012, xvii). [2] To assess and address the world problematique, I recommend that the public theologian rely on a global or even cosmic eco-ethic guided and inspired by Christian eschatology. Richard Baucham writes, “The Kingdom of God…is the renewal of all the creatures in their interrelationship and interdependence, what we could call an ecological renewal because it relates to the biblical writers’ sense of the interconnectedness and interdependence of God’s creatures” (Bauckham 2010, 168). Prescinding from the World Council of Churches, I summarize the proleptic vision in terms of a just, sustainable, participatory and planetary society. Should we adapt this to include a “planetary and galactic society”? [3] For ready-to-hand resources in Public Theology, just click on some of the following Patheos posts.From Athens to Jerusalem: Introducing Public Theology

The Public Theologian as Ecumenical & Ecumenic Pluralist

The Public Theology of Rudolf von Sinner

The Public Theology of Katie Day

The Public Theology of Binoy Jacob

The Public Theology of Robert Benne

The Public Theology of Paul Chung

The Drumbeat African Public Theology of Mwaambi G Mbûûi

The Public Theology of Valerie Miles-Tribble

The Public Theology of Kang Phee Seng

The Public Theology of Jennifer Hockenbery

Karen Bloomquist: Another Worldview Must Be Enacted Today

Critical Race Theory in Classroom and Pew

From Ukraine to World War Three in One Misstep

Gun Safety Prevarication and Legislation

Astrotheology as Public Theology

References

Adam, David. 2021. “How far with global population rise?” Nature 597:7877 462-462.

Ash, Caroling, Bianca Lopez, Jesse Smith, Savha Vignieri, and Brad Wible. 2022. “Time to Act.” Science 376:6600 1393.

Bauckham, Richard. 2010. The Bible and Ecology. Waco TX: Baylor University Press.

Bauman, Whitney. 2014. Religion and Ecology: Developing a Planetary Ethic. New York: Columbia University Press.

Bauman, Whitney. 2018. “Queering Authority in Science and Religion.” Unsettling Science Religion: Contributions and Questions from Queer Studies, eds., Lisa Stenmark and Whitney Bauman. Lanham MD: Lexington. 69-88.

Doran, Chris. 2017. Hope in the Age of Climate Change. Eugene OR: Cascade.

Dryzek, John, Richard Norgaard, and and David Schlosberg. 2011. “Climage Change and Society: Approaches and Responses.” In The Oxford Handbook of Climage Change and Society, by Richard B. Norgaard, and David Schlosberg, eds John S. Dryzek, 3-17. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gore, Al. 2012. The Future: Six Drivers of Global Change. New York: Random House.

Keller, Catherine. 2015. “Encycling: One Feminist Theological Response.” For Our Common Home: Process-Relational Responses to Laudato Si, by John B. Cobb, Jr., and Ignacio Castuera, eds. Anoka MN: Process Century Press, 175-186.

McFague, Sallie. 2008. A New Climate for Theology. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

Moe-Lobeda, Cynthia. 2013. Resisting Structural Evil. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Nadkarni, Nalini. 2017. “Ecology.” In Routledge Handbook of Religion and Ecology, by Mary Evelyn Tucker, and John Grim, eds Willis Jenkins, 412-419. London: Routledge.

Padgett, Alan and Kiara Jorgenson. 2020. “Introduction.” In Ecothology: A Christian Conversation, by eds Kiara A. Jorgenson and Alan G. Padgett, 1-14. Grand Rapids MI: Wm B Eerdmans.

Peters, Ted. 1978. Futures–Human and Divine. Louisville KY: Westminster John Knox.

Peters, Ted. 2018. “Public Theology: Its Pastoral, Apologetic, Scientific, Politial, and Prophetic Tasks.” International Journal of Public Theology 12:2 153-177; https://brill.com/abstract/journals/ijpt/12/1/ijpt.12.issue-1.xml.

Rahner, Karl. 1978. Foundations of the Christian Faith. New York: Seabury Crossroad.

Tucker, Mary Evelyn. 2015. “Climate Change Brings Moral Change.” For Our Common Home: Process-Relational Responses to Laudato Si, by Jr., and Ignacio Castuera, eds John B. Cobb, 187-189. Anoka MN: Process Century Press.