Here is a guest piece from author Gunther Laird, who recently wrote The Unnecessary Science:

Actuality and Abortion

Gunther Laird

As readers of A Tippling Philosopher are well aware of by now (having read the previous entry I wrote for this blog, “The Problems of Pure Act”), Edward Feser is one of the most popular and prolific defenders of the Catholic religion writing today. Those same readers will, of course, be aware that I contest his efforts directly in the new book I have recently published, The Unnecessary Science: A Critical Analysis of Natural Law Theory. While Feser has written mostly on metaphysics, he has addressed matters of morality as well, and as you can expect, my book attacks his worldview on those grounds as well. Of particular interest to contemporary readers, given the current fracas over Roe vs. Wade, are Feser’s arguments that abortion is immoral. These arguments—the sort that other Catholics such as Amy Barrett prefer–might seem quite different from most other pro-life claims because they are actually based on pre-Christian philosophy, specifically the Greek thinker Aristotle’s theories revolving around essentialism, actuality and potentiality. This entry is an excerpt from chapter 3 of my book that refutes Feser’s pro-life position based on his own Aristotelian reasoning.[1]

For new readers who haven’t read my previous entry, “Problems of Pure Act,” I must first provide a brief overview of these Aristotelian concepts. Rest assured that I go into much more depth on all of these topics in the actual text of the book, but I must be as concise as possible for the purposes of a single blog entry.

According to Aristotle (and his teacher, Plato, and their intellectual descendants, such as Feser), there is no way to make sense of the world around us without accepting the reality of Essences, which can also be called Forms. An Essence or Form is what defines a thing and distinguishes it from everything else. The specific wavelengths of light associated with the color green, for instance, define it and distinguish it from other colors, and the equidistance of all points on its surface from its center defines a sphere and distinguishes it from other shapes.[2] Now, it’s not just colors and shapes that have Forms. According to natural law adherents, everything has a Form. Concepts (there’s something that defines justice and distinguishes it from tyranny), artifacts (there’s something that defines a PlayStation 5 and distinguishes it from a Game Boy), and even living things (there’s something that defines a human being and distinguishes her from a squirrel or jellyfish).[3]

For the purposes of argument and saving space, let’s skip over the arguments Feser presents for essentialism (and against its alternatives, such as nominalism) and concede that he’s right. This, by the way, is one of the strengths of my book—in the Unnecessary Science, I concede many of Feser’s starting premises, but use them to refute the arguments he makes using them—by generously agreeing to fight on his own ground and on his own terms, my own position is shown to be that much stronger. Anyways, it’s one thing to say that we can distinguish between colors by referring to wavelengths of light, or shapes by referring to their mathematical properties, but how can we distinguish between living things? What, precisely, makes a human different from a squirrel or jellyfish? According to Feser, the answer lies in actuality and potentiality (sometimes called act and potency).

Act and potency are more Aristotelian terms that were initially created to explain how change could occur. In Feser’s view, they also prove the existence of God, but I’ve critiqued that specific argument in “The Problems of Pure Act,” so I’ll ignore that now—let’s focus entirely on ethics for the moment.

To put it as concisely as possible, “act” or “actuality” is how a given thing is or behaves right now, and “potency” or “potentiality” is how it will (or might) be or behave in the future, and both actuality and potentiality are determined by its Form or Essence. For instance, the Form of a rubber ball entails it is shaped like a sphere and made out of rubber, which defines and distinguishes it from, say, erasers (which are made of rubber but shaped differently), ball bearings (which are spherical but made of metal), or plastic triangles (which are both made of different materials and shaped differently entirely). Now, “being made of rubber” and “being spherical” are the ball’s actualities—they are what it is right now. But being a rubber ball—that is to say, having the Form or Essence of a rubber ball—also entails it has certain potentialities, or things it might possibly do in the future. For instance, if our rubber ball is sitting motionless on the floor right now, it is potentially rolling across the room or potentially flying through the air, if someone in the future were to give it a push or pick it up and throw it. Note as well, however, that there are some potentialities it does not have, because it will never display those sorts of behaviors or have those sorts of effects. For instance, a rubber ball will never produce nuclear power like a rod of uranium might, nor will it ever float off to the moon or chase someone around a room all by itself. It simply doesn’t have those potentialities.[4]

Now, according to Feser, the Form or Essence of a human being, that which objectively defines us and distinguishes us from everything else, is that of a “rational animal.” In the Aristotelian view, humans are the only creatures on Earth that have ever existed with the capacity for rational thought. Obviously, that’s debatable, but again for the purposes of argument let’s accept it. Now, review the previous paragraph: A thing’s Form or Essence entail what it is right now and what it might possibly be in the future (its potentialities). One corollary of this is that you can tell something’s Essence by what potentialities it possesses, because actuality (what something is right now) always grounds potentialities. So, Feser asks us to look at the human fetus under this metaphysical schema. According to him, a human is a rational animal, which means that anything which is either thinking right now or can think in the future is a rational animal (and thus deserves the rights attending to rational animals, or in other words, human rights, most notably the right to live). At first glance, it might seem like a zygote, embryo, or fetus definitely isn’t a rational animal because such tiny, underdeveloped organisms can’t think like adults or even children can. But according to Feser, they have the “potential” to reason in a way nothing else does. In “the natural course of things” a fetus will be born, grow up, and start to reason. That differentiates it from, say, hair or skin cells, which will never grow into thinking beings (barring the invention of some sci-fi cloning technology), or individual sperm and egg cells, which contain only half of a chromosome or blueprint for an actual human being. In other words, a fetus can reason in the future, even if it’s not reasoning right now. And if future behavior is one of a thing’s potentialities, and you can tell a thing’s Essence from its potentialities, then it follows, in metaphysical terms (even if it’s not obvious), that a tiny little fetus is indeed an actual human being. This is because human beings are (by dint of our Essence) the only creatures who have the potential to think. And therefore, killing a fetus is killing an innocent human being, which is absolutely forbidden in all circumstances.

There are just a few clarifications to be made before advancing to my critique of Feser’s position. First, he believes in the death penalty, which also involves killing a human being. Isn’t that an inconsistency? Not according to Feser, because of the key word I mentioned above—innocent. Assuming a fetus is human, it has committed no crime, because it hasn’t intentionally done anything wrong (you could argue absorbing nutrients from its mother is sort of a theft, but the fetus had no choice in the matter, as it can’t stop doing that even if it wanted to). Thus, a fetus is innocent, whereas grown criminals assumedly aren’t, and thus, since they are not innocent, it is morally licit to kill them. Again, we don’t have time to get into that branch of ethics here, so let’s concede it to Feser for the purposes of this entry. Secondly, even taking that into account, some philosophers, particularly “consequentialists” might argue it is permissible to kill innocent humans in some circumstances—in this case, a mother’s right to bodily autonomy outweighs the right of an innocent fetus to life, which it gains only after it’s born (and no longer needs someone else’s body to live). Feser considers consequentialism to be an abominable ethical system; in his preferred “natural law” theory, certain actions (killing an innocent rational animal, in this case) are absolutely condemned under all circumstances no matter what.

Yet again, there’s not enough room here to closely compare consequentialism and natural law theory, so we can concede even this point to Feser as well. In this blog entry, and in The Unnecessary Science itself, I will argue that a thorough Aristotelian analysis implies that zygotes and fetuses, before birth and the severing of the umbilical cord, do not actually possess the potential to reason and thus do not possess the Essence of “rational animality.”

First let’s take a closer look at Feser’s anti-abortion argument in The Last Superstition. He states,

…the features essential to human beings…being able to take in nutrients…to think, and so forth—are not fully developed until well after conception. But that doesn’t mean that they aren’t there…Rationality, locomotion, nutrition, and the like are present even at conception…as inherent potentialities…[this] doesn’t even mean “potential” in the sense in which a rubber ball might potentially be melted down and made into something else, e.g. an eraser. It means ‘potential’ in the sense of a capacity that an entity already has within it by virtue of its nature or essence, as a rubber ball qua rubber ball has the potential to roll down a hill even when it is locked in a cabinet somewhere. And in this sense a zygote has the potentiality for or “directedness toward” the actual exercise of reasoning…that a rubber ball doesn’t have, that a sperm or egg considered by themselves don’t have.[5]

The most obvious problem with Feser’s argument, in my view, comes with the example he uses right at the very end of that paragraph. How, precisely, could a zygote be much more “directed toward” becoming a rational animal than an individual egg or sperm cell could? This might sound strange to you and me, dear reader, but it shouldn’t sound strange to Dr. Feser. As he describes elsewhere in The Last Superstition (which I critique very heavily and at much more length in the sections on gay marriage in The Unnecessary Science), one of his major hobbyhorses is the idea that our sexual faculties “are directed towards” the production of more human beings. If that really were the case, then every egg cell, at least, would be an actual human being. Feser himself would say that the only reason eggs exist is to create new human beings; if we didn’t have sex (say we reproduced by budding or parthenogenesis), we wouldn’t have those egg cells. That means the egg’s final cause (another bit of Aristotelian jargon, explained at length in “The Problems of Pure Act”) is to become a human being, which also means it is “directed towards” human rational activity, it just “hasn’t yet fully realized that inherent potentiality.” The only thing the little egg needs to realize that potential is a little help from a little sperm, followed by nine months in mommy’s tummy. What makes the egg’s situation metaphysically different from the zygote’s? The only meaningful distinction between an unfertilized and fertilized egg, in terms of the potentialities towards which they are directed, seems to be the split second when the sperm hits the egg. Unless Feser can provide some account of why that exact moment represents a tectonic shift in the “directedness” of the egg cell, he would be forced to concede that a mere unfertilized egg is an “actual human, just one waiting to actualize its potentials” in the same way a zygote is.

Might that tectonic shift be a matter of chromosomes? One of the points for a zygote having its own distinct Form (that is to say, being a unique human being instead of a mere part of one, like some skin cells) is that it has its own distinct set of genes, different from those of its mother. The egg has an X chromosome from the mother, the sperm carries either the father’s X or Y chromosome, so when they come together, the resulting girl (if an X-sperm created an XX zygote) or boy (for an XY zygote) would have a distinct genetic blueprint that differed from both of the parents. But on closer thought, this is not the whole story. Both eggs and sperm have distinct “blueprints” by themselves. There are always slight variations in the single chromosome of the sperm and eggs created by the father and mother—these gametes are never just clones or identical templates, so to speak, the way cells of other body parts are. Even without a background in biology, this can be easily understood by thinking about siblings. If every egg cell and every sperm were exactly alike, every male and female child of a single couple would be identical to his or her brothers or sisters, because the exact same X and Y chromosomes would be creating them. In reality, of course, that’s not the case—except for identical twins (which are two people made from a single egg), there are always little differences among fraternal siblings. This is proof that each individual egg and sperm has a slightly different set of genes, which means they really do possess genetically distinct Forms, in the sense of being distinguished and individuated from others of their general type. Given their “directedness towards” becoming human beings, they would therefore seem to be actual human beings in the same sense a zygote is. But even Feser would admit this would be absurd.

Similar problems arise with Feser’s conflation of a certain substance being “intrinsically directed towards” a certain thing (in this case, a rational animal, or more specifically, reasoning at some point in the future) and actually being that thing. To again riff off of one his favorite examples, imagine a glass of water sitting at room temperature. That water is “intrinsically directed” towards becoming ice at cold temperatures. There is something inherent to water that gives it the “potential” to be cold and solid—if it were to remain a liquid at 0 degrees Celsius, or turn into violets, or explode or anything like that, it would not really have the Form of water and therefore would not actually be a sample of water. But the fact that a glass of water has “iciness” as a potentiality does not mean it actually is a block of ice until the temperature has lowered and it has actually frozen.

Imagine how silly it would be if you asked a waiter at a restaurant for some ice in your lemonade and he instead brought you a glass of water along with it, his excuse being, “well, this water is an actual block of ice, just one that hasn’t fully realized its inherent potentials.” I somehow suspect even Edward Feser would have a tough time tipping the guy extra for being an astute Aristotelian. Unhappily for the pro-lifers, the same reasoning applies to zygotes. There may be something intrinsic, a potentiality or blueprint “directed towards” rationality in a zygote, but only in the same sense that there is something intrinsic, a potentiality or blueprint “directed towards” ice in water. Until that potential is actually realized, it seems as silly to treat a zygote as an actual human being as it would be for a waiter to treat a glass of lukewarm water as an actual block of ice.

Aristotle’s doctrines of “primary actuality” and “secondary actuality” are of little help to Feser here. Earlier in The Last Superstition, Feser describes the distinction as such:

Since you are a human being, you are a rational animal; because you are a rational animal, you have the power or faculty of speech; and because you have this power, you sometimes exercise it and speak. Your actually having the power of speech flows from your actually being a rational animal; it is a ‘secondary actuality’ relative to your being a rational animal, which is a ‘primary actuality.’

What this means is that “the zygote, given its nature or form, has rationality as a ‘primary actuality’ even if not yet as a ‘secondary actuality.’”[6]

The key phrase there is “given its form.” We can agree that a zygote has a “primary actuality” of rationality only if we agree it is an actually rational animal in the first place. But as the examples given above should hopefully show, it is far from obvious that a precursor to a rational animal actually is a rational animal itself. That being the case, if the zygote possesses a different Form, even if it has the potential to become a rational animal, it does not in and of itself have rationality as a primary actuality. The example of the block of ice comes to mind again: Ice has the “primary actuality” of being cold and solid, and also has the secondary actuality—that is to say, an ability that flows from its primary actuality but is not necessarily always expressed—to cool a drink. Any block of ice will have this power even if it isn’t in a glass of lemonade. But it must be frozen into a proper block first—a glass of lukewarm water does not have the primary actuality of iciness and therefore no secondary actuality of a capacity to cool. Only when the water has been given the Form of ice through freezing, and only when a zygote has been given the Form of a rational animal (a soul) through gestation and birth, can either be said to actually be icy or rational.

Admittedly, there may be a disanalogy here: The zygote is a living thing, whereas a glass of water would be an inanimate object. Doesn’t the zygote have some inherent principle of growth and operation that makes it different from water, which only has a principle of operation and no inherent tendencies of growth or autonomous behavior? This is most likely the argument that the Thomists John Haldane and Patrick Lee would use, and Feser relies quite heavily on their analysis to buttress the ones he gives in Aquinas and The Last Superstition. On closer inspection, however, a sharp-eyed reader can see that Haldane and Lee’s arguments are not entirely airtight either.

The pair tells us that “the case of foetal development involves an intrinsic principle of natural change in a single substance. This change involves the internally directed growth toward a more mature stage of a human organism, and so the cause of this change, the embryo itself, is already human.” According to the authors, an embryo can be said to be “internally directed” thanks to its “epigenetic primordium.” The term derives from two words: “the ‘primordium’ [is] ‘the beginning or first discernible indication of an organ or structure’, while ‘epigenetic’ is used to mean ‘being developed out of without being preformed.’”[7] Since this primordium—the first discernible indications of organs which will gradually develop as part of a final cause—is present only after the sperm hits the egg, that moment of conception can be considered the moment at which a new human being is formed (or Formed, or ensouled, whichever you like).

But at the same time, Lee and Haldane also mention, “In mammals, even in the unfertilized ovum, there is already an ‘animal’ pole (from which the nervous system and eyes develop) and a ‘vegetal’ pole (from which the future ‘lower’ organs and the gut develop).”[8] This would seem to fulfill the criteria of an epigenetic primordium: The first discernible indications of organs, which are not pre-formed but will develop naturally after they have made contact with a sperm cell. Since one of these blueprints, so to speak, is of the nervous system, the individual egg could be said to be “directed towards” the rationality associated with that nervous system. That would mean an unfertilized egg would be an actual human in almost the same way Feser, Haldane, and Lee say a zygote is an actual human. But, again, this seems absurd.

Absurd, they might say, because an unfertilized egg contains no inherent principle of growth. An egg without a sperm attached to it will just sit there until it’s eventually flushed out (a process, I hear, that causes quite some inconvenience every month). An egg combined with a sperm, however, has its own unique genetic blueprint and something that makes it start to divide and grow in size. Since

…there is no extrinsic agent responsible for the regular, complex development, then the obvious conclusion is that the cause of the process is…the embryo itself. But in that case the process is not an extrinsic formation, but is an instance of growth or maturation, i.e., the active self-development of a whole, though immature organism which is already a member of the species, the mature stage of which it is developing toward.[9]

This would be convincing…if Haldane and Lee hadn’t forgotten about a very important extrinsic actress indeed: The zygote’s mother. A zygote is not really like an adult cat or dog or squirrel or other animal Feser uses as examples of natural substances or animal souls.[10] A grown, independent animal is capable of taking in nutrients, reproducing, and carrying out all its other behaviors (barking, meowing, burying nuts, whatever) on its own volition and does not necessarily rely on any other entity to do it for them. In other words, these animals operate entirely according to their intrinsic principles, though bad fortune (such as predators or local famine) can frustrate these principles. A zygote, on the other hand, relies entirely on its mother’s body to carry out its distinctive operations. It first must attach itself to the uterus before it will grow, and none of the “epigenetic primordia” it contains will ever actually become the organs (much less the rationality) they “point towards” unless the mother’s body provides it nutrients and proper direction 24/7 for nine months.

In a meaningful sense, while a zygote may be “directed towards” growing in that it possesses a certain genetic blueprint conducive to that end, the little thing is not actually growing itself. Rather, the mother’s body is actively stuffing nutrients into it and moving the process along. It does not seem to be an intrinsic principle of the zygote that spurs its growth, but the extrinsic action of the body in which it is found. If zygotes really did possess some intrinsic principle as Haldane, Lee, and undoubtedly Feser hold, they would be able to nourish themselves and grow into little rational animals entirely on their own. But as we all know, this is impossible—a zygote separated from its uterus in some way will quickly wither and die. Even if there were some way to keep it alive—an artificial womb from Brave New World, for instance—that womb would still be providing nutrients and direction for the organism’s growth. There would still be an extrinsic, external agent responsible for the changes the zygote experiences, it would just be an artificial, science-fiction agent rather than a natural mother.

Neither is it any good to say the “blueprint,” the full set of chromosomes (with two being XX or XY) contained in a zygote constitute the “intrinsic principle,” at least if merely having an “intrinsic principle” that is not yet fully realized makes an entity of the same type as a fully-grown example. As mentioned earlier, an unfertilized egg contains a sort of blueprint for the nervous system all on its own, it merely needs a handsome, dashing sperm to complete the blueprint and begin the next step of the process towards which it is “directed.” If the Thomist Trio wishes to say a zygote is an actual rational animal that is just waiting to realize its potentials after nine months and with the aid of many nutrients, we can say an unfertilized egg is an actual rational animal that is just waiting to realize its potential with the aid of a single sperm, nine months, and many nutrients. As Feser might say, an incomplete or damaged blueprint is still a blueprint, and the half-chromosomal-load of a human egg certainly counts as an incomplete blueprint.

Equally problematic is the word “blueprint,” as a blueprint itself contains no intrinsic principle that can be actualized without the aid of an external actor. Imagine you give a builder the blueprints for a house. It would be silly for either you or him to act as if the blueprint itself were an actual (if incomplete) house, because the blueprint is merely providing a set of instructions. The builder must provide the materials and do the work of building a house, even if the blueprints are directing him in a sense. By the same token, the zygote’s distinct chromosomes serve as a blueprint for a unique human being, but that human being does not exist yet. Only when enough time has passed and the mother’s body has provided enough nutrients (she is the builder in this case) can we really say a new human has come into being.

Under Feser’s own lights, then, a consistently Aristotelian outlook makes abortion more, not less, justifiable. When we accept three important Aristotelian views (Realism [that things in the world actually have mind-independent Essences or Forms], the idea that a thing’s potentialities tell us what Form it instantiates, and the idea that substantial Form is determined by an inherent principle of growth), we find that since a zygote lacks inherent (as opposed to externally-powered) growth, it does not truly possess the potentialities associated with the Form of a human, and thus is not truly a human. Consequently, it does not possess a right to life all humans do. I would say that’s a hefty metaphysical argument pro-choicers could add to their arsenal.

We are then left with one more problem: Where, precisely do we draw the line between a merely proto-human zygote and a fully human child? It is a very important question, at least to guys like Feser: If zygotes really aren’t rational animals, then it would be acceptable to destroy them, but since children really are rational animals (just immature ones), we can’t simply kill them. Aquinas thought that growing proto-humans took on the full Form of Humanity (that is to say, their souls) at about forty days into development, but this was due to the primitive knowledge of embryology available to him at the time. Given that the Form of Man is being a rational animal, an ethics based on Forms seems to entail that any human-seeming organism would only be truly human once it began to demonstrate rational activity. But as we all know, babies aren’t very rational, so this would imply the absurd conclusion that infants and toddlers weren’t really human (and that abusing or killing them would be less morally severe).[11]

In order to avoid this conclusion, Feser, Lee, and Haldane had to resort to the concept of “epigenetic primordia” and the assertion that a zygote containing a blueprint directed towards being a rational animal (eventually) counted as having an intrinsic principle—making it an example of an actual rational animal, merely an immature one. But, fortunately, even under my own riff on an Aristotelian framework, where zygotes are not rational animals, it is possible for me to maintain that newborns are fully human and deserving of rights.

The key lies in the intrinsic principle of growth and behavior mentioned earlier in relation to animals. We have established that zygotes do not possess this principle because their growth and development is dictated entirely by an external actor (the mother’s body). However, when a baby leaves the womb, loses the umbilical cord, and takes the first breath out in the world, he or she gains that intrinsic principle. Yes, it is true that babies and toddlers are just about completely helpless, and that they need to be fed and cleaned by external actors to avoid starving to death (which obviously entails they are entirely un-rational). But even though babies are helpless, they are not as helpless as a zygote, embryo, or fetus. Babies are capable of manifesting behaviors all on their own and exerting some control over their environment, even if only in a very thin sense of crying loudly to get someone to notice them. Their independent actions evince a sort of intrinsic principle influencing the world around them, analogous to the way a dog barking or a cat meowing for food evinces an intrinsic, independently-operating behavior influencing the world, which tells us those things are dogs or cats. A proto-human, however, cannot influence anything in that way. Even a developed fetus, no matter how much it kicks or rolls around in the womb, cannot change the chemicals of the uterus surrounding it, nor how many nutrients the uterus provides it. We can say the fetus’s principle of growth is extrinsic, located in the mother’s body, while the newborn’s principle of growth is intrinsic, rooted in its own behaviors (even if they only serve to get others to feed it). Since the Thomists require a “blueprint” pointing towards rationality (which babies certainly have, given they’ll grow to be at least somewhat rational in a few years), and an intrinsic principle propelling growth towards that goal, babies fulfill both conditions, while zygotes have only the former. So it is demonstrated that we can justify abortion on Aristotelian-Thomistic grounds without necessarily condoning infanticide.

As always, I hope you’ve enjoyed this piece—and if you did, you’ll consider buying The Unnecessary Science, where you’ll find this argument expanded on, as well as many others that will prove massively useful to anyone interested in refuting “natural law theory,” which has taken a great deal of contemporary importance thanks to the preponderance of right-wing Catholics such as Clarence Thomas and, soon, Amy Barrett on the United States Supreme Court. You can buy a physical copy here.

If you’d prefer an ebook, don’t worry, the ebook version will be out before the end of the month—please look forward to it! You’ll have everything you need to send Thomists packing at the touch of a button on your computer or even a few swipes of your smartphone if you have Kindle, Kobo or Nook!

NOTES

[1] As is the case in the text of The Unnecessary Science, I reference Feser’s work with acronyms since I cite them so much. Here, The Last Superstition is TLS and Aquinas: A Beginner’s Guide is AQ.

[2]TLS, 31-35, AQ, 16-24. Essence, Form, and Nature each connote slightly different things in the most technical usage, but the distinction isn’t important in this context, so here we will use the terms interchangeably. I should note here that I am capitalizing all these terms in my own text, though leaving them uncapitalized when directly quoting from other authors, to differentiate the specifically philosophical terms from the common verbs and adjectives which denote different things.

[3] Ibid.

[4] TLS, 50-55.

[5] TLS, 129.

[6] TLS, 56.

[7] John Haldane and Patrick Lee, “Rational Souls and the Beginning of Life (A Reply to Robert Pasnau),” Philosophy 78 no. 4 (2003), 537.

[8] Ibid.

[9] John Haldane and Patrick Lee, “Aquinas on Human Ensoulment, Abortion and the Value of Life,” Philosophy 78, no. 02 (2003), 271.

[10] TLS, 121. The specific term Feser uses is “sensory soul,” but that’s not relevant to the discussion at hand.

[11] AQ, 141.

Stay in touch! Like A Tippling Philosopher on Facebook:

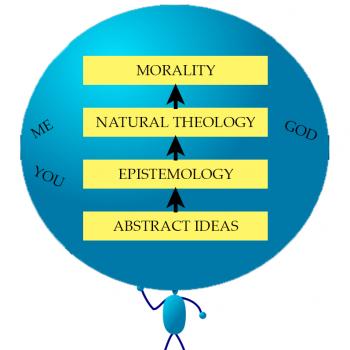

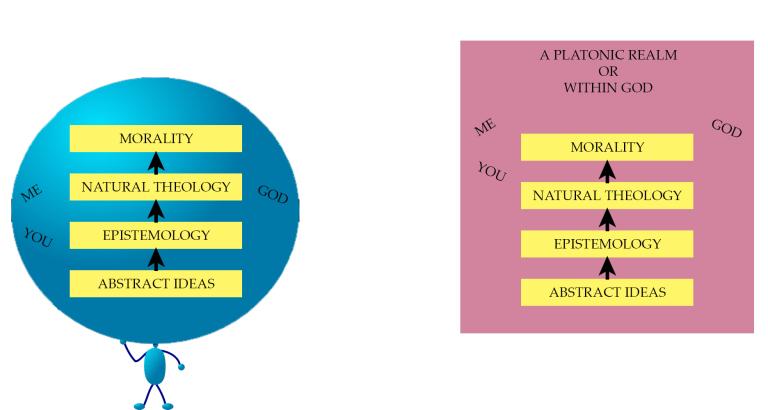

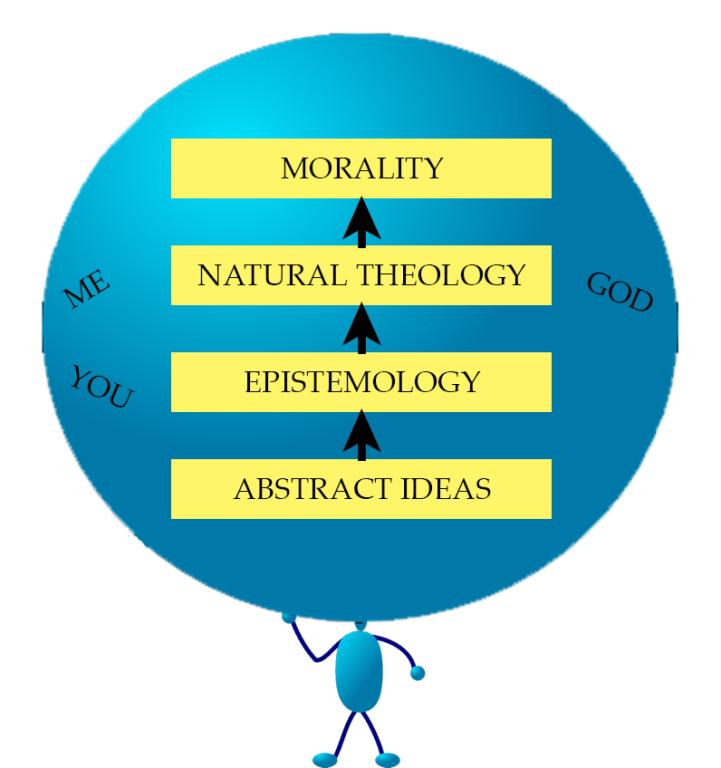

This is JP. He is a conceptual nominalist. He thinks more people should be like him.

This is JP. He is a conceptual nominalist. He thinks more people should be like him.