Luke Breuer kindly responded to my request and provided a critique of my position of conceptual nominalism recently. I hope to look at his claims and analyse them in my reply here today.

I have a forthcoming book that sets out my position with a lot more depth and clarity (Why I am Atheist and Not a Theist), so you’ll have to grab that out to get to greater grips with my position. For other background reading, see the links at the bottom of this piece or throughout.

One of the first things he implied is that the position is not common:

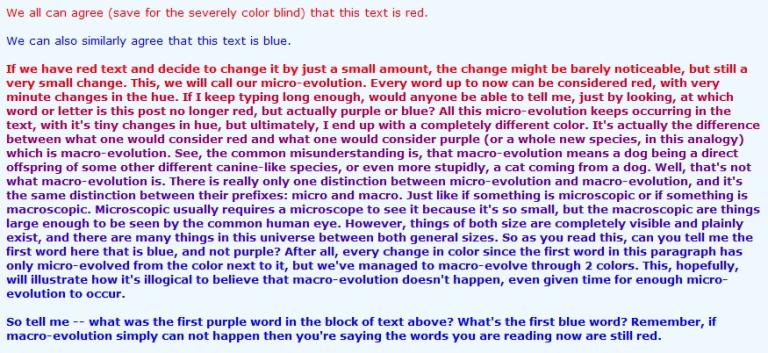

Jonathan is a pretty big fan of ‘conceptual nominalism’, saying that “the discussions [about concepts/universals] are crucial to the rest of metaphysics”. It’s not a common term: google:

"conceptual nominalism"returns only 1250 results, of which 92 come from Tippling. See for example The Pertinence of Nominalism to Religious and Philosophical Debates.

Just to clarify, the term is most often used as “conceptualism”, which itself returns a much bigger 593,000 results, so is a lot more common as an idea when termed in this way.

Definitions

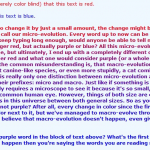

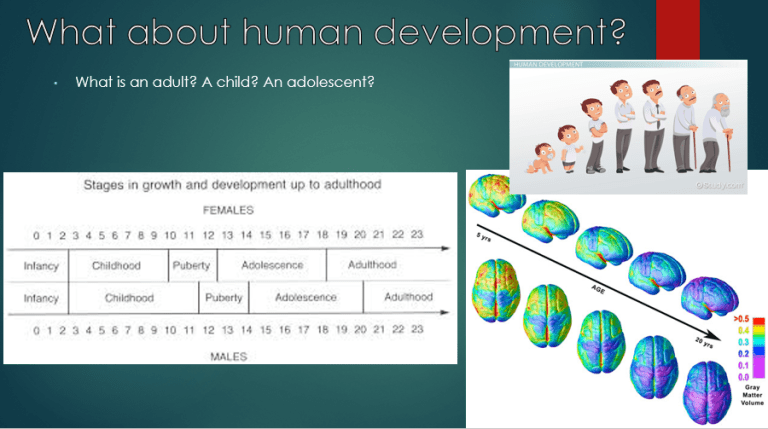

My position is that abstracta – and these can include “universals” like redness, as well as “morality”, “justice”, “hero” and “chair” – exist only in the minds of conceivers. When we agree, we write dictionaries and encyclopedias, and when we feel strongly about certain (moral, but also definitional) abstracta, we encode them into law, and ideally enforce them. When we disagree on previous encoding, we change documents (e.g. Amendments to the Constitution), change laws or vote governments out in order to do this.

Life and history have been a constant battle towards agreement. We tend towards agreement. Or do we? Look at the polarisation of US politics and then ask whether we do. One side claims they have access to objective morality because they have God on their side, the other sometimes claim they have it because they have inalienable human rights on their side. Of course, even if objective abstracta such as morality did exist, neither side can indubitably know that they have jibed with it in their beliefs. And so we continue to argue, using philosophy and rationality (hopefully) to try to arrive at reasonable conclusions.

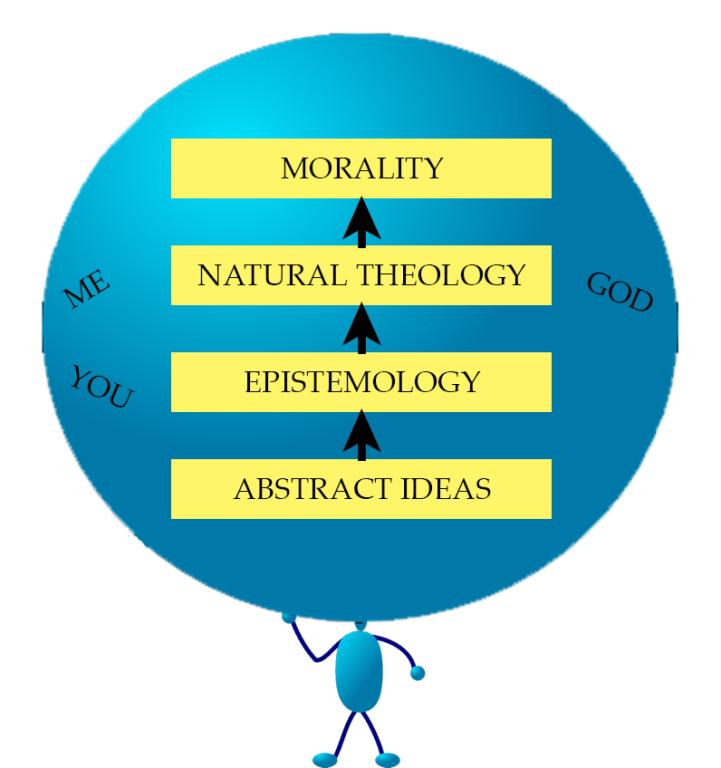

It is interesting that he rightly links conceptualism to morality since the term refers to abstracts and abstract ideas, and morality is arguably one of the most important members of this set. He lays it out in this way:

-

Objective

- There is some cosmic enforcer of justice who will ultimately get his/her/its way.

- There is some mind-independent Form of Justice we can (and will) access increasingly well.

-

Subjective/Relative

-

Human concepts of justice will change over time and they will judge the situation to be closer and closer to the contemporary notion of justice as time goes forward.

-

Where he is using justice qua morality as his exemplar, one could substitute any abstract idea or network of ideas. His option I.1 is interesting. Perhaps it is only because he is exemplifying justice, but it seems he is only seeing objective justice in terms of a divine entity enforcing their will, or some form existing in, I presume, some naturalistic aether. This may be the distinct quality of justice such that it is only a thing when it is enforced? But, still, we have the idea of justice. And the idea, I would argue, is conceptual, and would not exist if there were no sentient minds that could conceive of it. We disagree on exactly what justice entails, as I did on the blog with Dave Armstrong and Paul Hoffer recently.

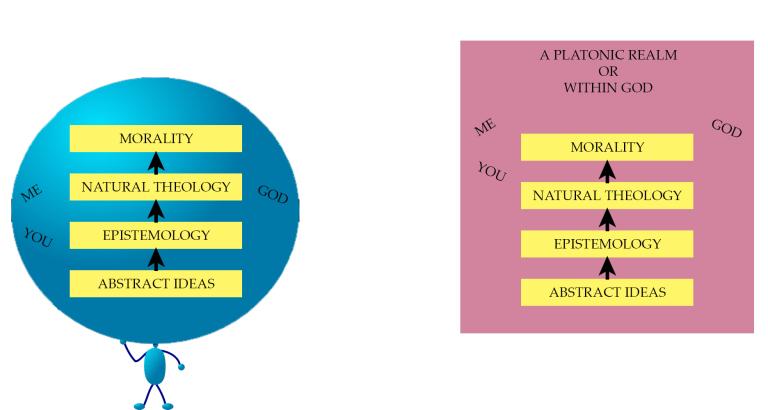

For objective abstracta, the options appear to be:

- Some cosmic enforcer (divine entity) instantiating whatever abstract is being considered, in some way either benchmarking it, or having it exist in their form, somehow.

- Abstracta existing in some non-material aether, either

- in a supernaturalism framework (with, say, a god existing), or

- in a naturalistic framework.

2.1 and 2.2 are essentially synonymous to me: you would have to posit some other realm – some non-material realm – were abstracta could exist independent of sentient minds.

1. is certainly interesting. What does it really mean for abstracta to be objective if they exist in the form of another sentient entity, even if that is a divine being? To me, it is still subjective – just that the subjective mind is way more impressive than mine. I can’t really make much sense of this because it suffers from the Euthyphro Dilemma issues: If something is good because it inheres in God’s nature, then it is devoid of moral reasoning. It is good because God (might makes right). But if it is good because moral reasoning argues for it being good, then it is grounded in moral reasoning. Objective morality existing merely because it is in God’s nature (devoid of moral reasoning) then makes such objective morality incoherent or deeply undesirable.

This is more obviously the case here for morality and perhaps this won’t make much sense for all abstracta. What does this say about redness, as a universal, or hero-ness, or chair-ness? Are we to understand that these abstracta are grounded in God in some way? How does God hold the key to their perfect Platonic forms? Can you even conceive of a perfect chair (devoid of functional contexts to one chair is better suited as a chair on one scenario, but worse in a second scenario)? Let alone a perfect chair being grounded in God or some cosmic enforcer, or, failing that, existing in some naturalistic aether?

What happens when I make up a new abstract idea, like a phnackstarg: the peeling edge of kitchen sideboard if it is over 103 years old, but under 107? Does this now exist in an objective aether, or is it grounded in God? What nonsense is this?

God makes no sense of abstracta to me because objectivity makes no sense of abstracta to me. They are contextual and/or conceptual by nature.

If we refer to Luke’s II.1, then his definition jives perfectly with what we actually experience in the world, over time and place:

-

Human concepts of justice will change over time and they will judge the situation to be closer and closer to the contemporary notion of justice as time goes forward.

Of course things will tend toward our contemporary understanding since that is how we arrive at understanding – that is how thought and development, human history and philosophy work. And we see differences in understandings of justice over time and place precisely because there appear to be no objective values existing in some other aether – or if there are, we can’t access them or even know we are accessing them.

This pretty much dovetails with criticisms of divine command theory (see my piece “16 Problems with Divine Command Theory“). There really are so many parallels there (go read it).

So just dealing with Luke’s definitions, I broadly agree – though with some refinements – and think that conceptualism is prima facie, at least, evidenced in the world through time and place.

Luke’s disagreements

Luke starts out his disagreements with this one:

(A) Conceptual nominalism is self-undermining. Consider the attempt to affirm both:

-

Concepts are about reality, but never refer perfectly.

-

Conceptual nominalism is a concept about concepts, and refers perfectly.

So A.i takes one heck of a lot of unpacking, epistemologically speaking, for such a simple sentence. What is reality? This gets back to our idealism vs materialism debate, and how sure we can be that a material world even exists outside of our mental experiences.

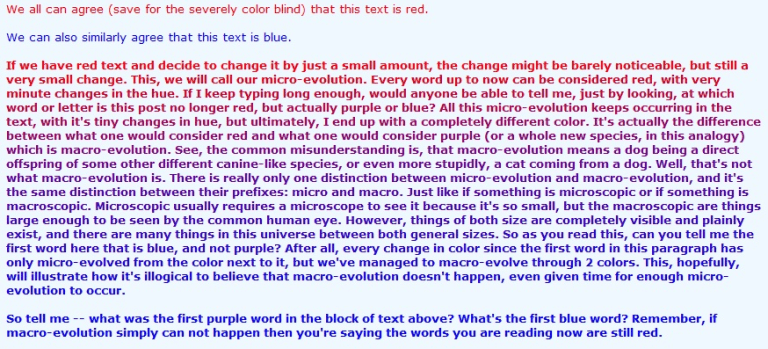

Luke’s point, as we will see, is actually an epistemological one, as opposed to an ontological one (or its an epistemological statement about ontology):

That means conceptual nominalism is ostensibly about a whole bunch of space-time regions of matter-energy. Either it refers perfectly excepting itself, or it does not refer perfectly and is false.

The word “refers” is a verb concerned with epistemology, as opposed to an actual state of affairs. And, considering epistemology, Luke also assumes (and fairly understandably and commonly) a correspondence theory of truth (CToT). That is:

a) a material world exists outside out minds.

b) that we have concepts and beliefs about that external world.

Whereby Luke believes/assumes that truth is where a belief or claim corresponds perfectly with the external world. But…

c) (as per Kant) we can never know the external world in itself, as conceptual subjective beings

d) we cannot know how accurate our beliefs about the external world are, even if it does exist.

So whilst the CToT may or may not hold, we can never know whether anything is true within that framework.

Now, Luke tries potentially a fast one here in saying that, in a Cartesian sense (cogito ergo sum – I can only indubitably know that I, some kind of experiencing entity, exist, by point of fact of experiencing), we cannot know that conceptualism holds. I always hold that everything outside of cogito ergo sum is a probability, in terms of knowledge, and based on a whole load of axioms. That my partner and children exist is a probability, not a certainty. I could be dreaming, living in The Matrix, and what-have-you (that I am not, I hold as an axiom). I can’t prove I am not, even if I really believe I am not. I cannot be indubitably certain about this.

So, probability.

How does this affect conceptualism?

Well, just like any other claim, it could just be a probability such that I am pretty sure, but not certain, that it holds. Sure. So?

Or, perhaps it can be even more fundamental than that. Perhaps conceptualism is indeed the most certain of claims outside of cogito. It is Kantian in its epistemology. I can’t prove anything beyond experience, and conceptualism is, in a sense, experience about stuff. And in experiencing things (including other minds), I build up frameworks and maps about reality. But my maps are not the terrain – your maps are not the terrain either. So we can’t know that the terrain exists, but whatever does or doesn’t exist in reality, we build maps to navigate ourselves through experience.

I can’t know (in a Cartesian sense) whether morality exists, just like I can’t know if a chair exists. Conceptualism is to say that no objective (mind-independent) abstracta exist. To say they do is to say there is “mental” or abstract reality outside of our minds. But, in a Kantian sense, just like we can’t know a material thing in and of itself (say, the matter of a chair), we can’t know an external mental thing in and of itself.

So there is subjective interpretation and conceptualisation of external entities, no matter what those external entities are made of.

The only other option, if you really, really want to argue for objective abstracta (e.g. morality) is to say that they exist naturally within one’s mind. So I can access objective morality because it somehow inheres within me as a mentally experiencing entity. But, then, how does this explain everyone’s often different moral evaluations, or experiences and beliefs about these abstracta? And this also defies the definition of objective abstracta where objective means mind-independent.

But to refer back to Luke’s original claim (“Concepts are about reality, but never refer perfectly”), concepts might well refer perfectly; we just don’t know. So, this is arguably just an incorrect premise.

This should be enough to discount such an approach as Luke’s.

I will return to look at his second objection in a further piece.

For background, see:

- The Pertinence of Nominalism to Religious and Philosophical Debates

- Philosophy 101 (philpapers induced) #2 – Abstract objects: Platonism or nominalism

- Natural Law, Essentialism and Nominalism

- The Kalam Cosmological Argument: Creation and Nominalism

- Species Do Not “Exist”: Evolution, Sand Dunes and the Sorites Paradox

Stay in touch! Like A Tippling Philosopher on Facebook:

You can also buy me a cuppa. Or buy some of my awesome ATP merchandise! Please… It justifies me continuing to do this!

I have written in the aforementioned book that largely deals with the idea of nominalism and how it affects the Kalam Cosmological Argument. As I set out

I have written in the aforementioned book that largely deals with the idea of nominalism and how it affects the Kalam Cosmological Argument. As I set out