I recently posted on the wide range of alternative scriptural materials that survived in the early Irish church – and apparently, in very few other places in the Christian world.

But it is in the realm of gospels that Ireland produces the most surprising findings. Throughout the Middle Ages, scholars across Western Europe make startling references to gospels otherwise thought lost, often presented under the guise of a Jewish-Christian gospel. We can debate at length what exactly they might have been referring to, but often, we can track their citations back either to the influence of Ireland, or to Irish monasteries founded in Western Europe. Irish clergy used some very strange texts, and even treated them as canonical.

By the eighth century at the latest, Irish scholars commenting on the canonical gospels cited alternative readings that they found in a work they called the Gospel According to the Hebrews, and the work continued to be used through the twelfth century. Around 850, it was quoted by Sedulius Scottus (“the Irishman”), the scholar who was so critical in transmitting Irish learning to Latin Europe. Almost casually, he refers to the apostle James swearing not to eat until after Christ had risen from the dead, “as we read in the Gospel according to the Hebrews.”

We can’t be wholly sure that this is the same “Hebrews” that is cited by earlier scholars like Jerome. Medieval writers were often careless about quoting the titles of the works they cited, and they applied generic names like “the Hebrew Gospel” to a wide variety of mysterious texts. In this case, though, the work that the Irish had certainly fits those ancient characterizations. At no point do they suggest that this work was obscure or hard to obtain: it was just part of familiar Irish libraries.

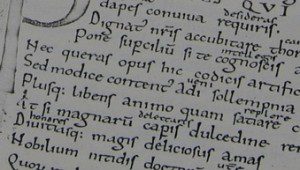

Around the year 1000, moreover, an unknown European monastery compiled a manuscript of the Roman writer Sallust, using for the cover some discarded parchment. That trash, though, proved to be a fragment of an older Irish missal or sacramentary, showing appropriate readings for different feasts and special occasions. At the Mass of the Circumcision, the reader would have begun “Here begins the reading from The Gospel According to James, son of Alphaeus.” This is exactly the format that would have been used to introduce a passage from canonical Mark or John, with no indication that this text held any different status.

From the text quoted, a brief account of Jesus’s circumcision, it is impossible to know just what else might have been in this gospel, but it bore a weighty name. In the sixth century, the Western church had already known (and rejected) a Gospel under the name of James the Less, that is, the son of Alphaeus.

Successive invasions and waves of destruction have uprooted much of Ireland’s early Christian culture, especially from its most glorious age that ran from about 550 through 800. Enough, though, remains to suggest that Ireland in these years must have retained a library of alternative Christian texts that would have astounded – and perhaps horrified – mainstream church authorities in Rome or Constantinople.