I described the Egyptian monk Shenoute and his fierce wars for orthodoxy in the fourth and fifth centuries. If we look at his struggles against Egypt’s still continuing Gnostic movement, it helps us understand the context of many of the key books and documents that have surfaced in modern times, revolutionzing our understanding of early Christianity.

Egypt had always played a key role in the development of Gnosticism, which survived even after the triumph of orthodox Christianity. Even in the fifth century, remarkably, the mainstream church still saw Gnostics as an enemy needing to be fought, especially when they seemed to have established footholds in some monasteries.

Shenoute wrote against both Origenists and Gnostics, and (not surprisingly, being Shenoute) he also undertook direct action. One of his campaigns, against the temple of Pneuit near Akhmim, around 412, was probably directed against still-surviving Sethian Gnostics. He particularly wanted to seize their “books full of abominations” – presumably, a collection very much like what was found at Nag Hammadi in modern times.

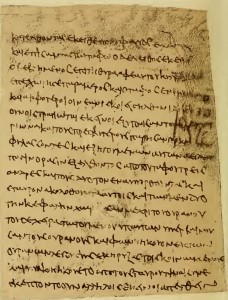

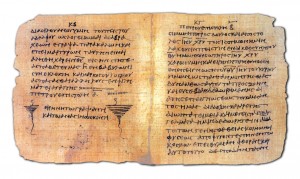

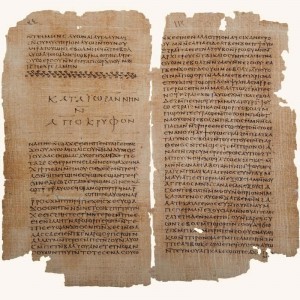

Mentioning the name of Nag Hammadi draws our attention to the local geography of the region, roughly between Sohag and Qena on the upper Nile. This was the site of a cluster of extremely important monastic sites, and also of critically important document finds. Shenoute’s White Monastery was near Sohag, with the Red Monastery nearby. In the 1890s, Akhmim itself (ancient Panopolis) produced the famous Berlin Codex that contains such treasures as the Apocryphon of John, the Sophia of Jesus Christ, and the Gospel of Mary. Were these the “abominations” that Shenoute was seeking?

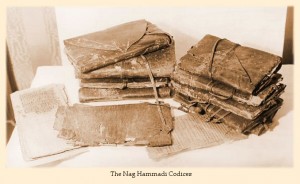

Some sixty miles away stood the ancient house of St. Pachomius at Chenoboskion, and Nag Hammadi itself is in the neighborhood. In fact, the Hammadis were originally a Sohag family, who gave their town to the new settlement. It’s highly plausible that the library found in modern times was once located at the monastery of Chenoboskion, although it is open to debate exactly what use the monks might have made of it. Another major document find, although more orthodox in content, surfaced nearby at Dishna, again near an ancient monastery: we know these as the Bodmer Papyri.

Just to be comprehensive, we might move south of Qena to the Luxor area, and Medinet Habu. It was here, in 1769, that Scottish traveler James Bruce bought the so-called Bruce Codex, the first of the great Gnostic texts to be rediscovered in modern times.

What we can say, then, is that Shenoute’s area abounded in monasteries, and some at least held documents that he would have found highly suspect. Quite possibly, his becoming abbot of the monastery in 388 may well have convinced the owners of the Nag Hammadi library that rapid concealment would be highly desirable.

Not surprisingly then, Shenoute’s hatred of Gnosticism was linked to his profound suspicion of apocryphal texts of all kinds, particularly alternative gospels. As we know today, Egypt was extremely fertile in such texts, which were commonly associated with Gnostic groups. Shenoute was comprehensive in his denunciation. He asked,

Who will say that there exists another gospel outside of the four gospels and not be rejected by the church as heretical? … What did the apostles lack and all the saints? What is not in the scripture, through the Holy Spirit who speaks in them, that we shall look for apocrypha?

His use of the term “apocrypha” may mean that he is referring to texts that we know from Nag Hammadi, including the Apocrypha of James and John.

We can understand why Shenoute was hunting for Gnostic books. But the more interesting question might be, why were other monks likely using them? Did they still value them for their religious truth? Or were they mining them for evidence to denounce heresy? Scholars have debated this for years. Increasingly, I think these were books that monks themselves were reading for enlightenment and spiritual revelation, or at least had at some stage in their institutional development.

And that gets us to the whole question of the complex origins of monasticism, its Middle Eastern predecessors and parallels.