In the two or three centuries before Jesus’s time, Jews became highly interested in angels, to whom they assigned identities and personal names. That represents a major shift from the well-known scriptures of the sixth and fifth centuries BC that we find in the canonical Old Testament. Something had happened between those periods, but what?

Exploring this question actually tells us a great deal about how we write our religious history, and how we treat influential ideas like Dualism.

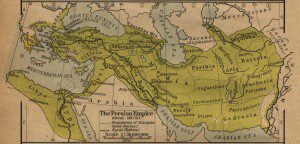

One obvious answer was that between the sixth and fourth centuries BC, the land of Israel was under the political control of Persia. The Persian Empire acquired Palestine around 540 BC, and it was the Persian king Cyrus who permitted the Jewish exiles to return to their homeland. Persia held the land until the conquest by Alexander the Great in 330. As we see in texts like Ezra and Nehemiah, Jews were part of a Persian political world, and that dominance lasted for a solid seven or eight generations.

Ezra and Nehemiah also show us the ferocious attempts that Jewish elites made to defend and purify their faith, with strict bans on intermarriage. Yet it was exactly in these years that Judaism seems to have adopted many themes and ideas from Persia’s distinctive religious system.

But the story is neither simple nor straightforward. One basic problem is that we really don’t know as much as we should about the Persian system and the great prophet Zoroaster (Zarathustra). Based on analogies with Western religions, we tend to assume that Zarathustra had some great insight, founded a religion, which eventually became the official creed of the mighty Persian Empire. Well, yes and no.

By the way, the standard resource for these matters is Mary Boyce‘s three volume A History of Zoroastrianism (Leiden: Brill 1975-1991).

Much remains obscure about Zarathustra, to the point that scholars argue whether he lived in the 14th century BC or the 6th, or some point inbetween. He has variously been located in Western and Eastern Iran, and in Central Asia. We do know that he was very slow to make converts, and his ideas merged gradually with older Iranian ideas, so they were not initially practiced in pristine purity. Although his system was probably accepted in Achaemenid Persia (550-330 BC), and Ahura Mazda was venerated, we don’t find the prophet’s name in inscriptions. If we did not know about the Zoroastrian faith from other sources, we would discover virtually nothing about it from a contemporary traveler like Herodotus, c.430. We are certainly not dealing with anything like state-sponsored Dualism!

Very important for present purposes, Zoroastrianism itself changed dramatically over time, and the faith as it existed in, say, 500 BC looked quite different from that of 200 or 500 AD, not to mention the surviving Parsi system that still exists in India. Just because the religion looked very recognizable in Jewish or Christian terms in 500 AD did not mean that this was its form eight hundred years earlier, or that we can trace a direct influence from Persia to Judea.

We also have to be careful about what we might call contamination from the Manichaean religion that emerged much later, in the third century AD, and which did preach naked Dualistic warfare between the forces of Light and Darkness. That is quite different from Zoroastrianism as we find it during the era of Persian rule over Judea.

The closest resemblance to later ideas is in the basic Persian notion of the titanic struggle between competing forces, originally Truth and Falsehood, so that the world divided between followers of Truth and followers of the Lie. Later, this was framed as a struggle between Light and Dark, very much as we would later find in Qumran texts like the War Rule.

This strong emphasis on the Lie has many resonances in both Judaism and Christianity. The sect that composed the Dead Sea Scrolls denounced their enemies with titles like “Man of the Lie” and Spouter of the Lie.” Jesus denounced the Devil as a liar (pseustes) and Father of Lies (John 8.44).

Persian religion presented great spiritual figures, associated with cosmic warfare. Persian religion originally had its spirits, ahuras and daevas, much like Hindu counterparts. For Zoroaster (Zarathustra), though, these became more Dualistic in tone, with the good ahuras in combat with the evil daivas. His faith also taught the idea of a final Judgment, and the end of the age. To quote William W. Malandra’s excellent essay in the Encyclopedia Iranica, “Zarathustra articulated the kernel of the idea of a Savior figure, the Saošyant … who would arrive in the future to redeem the world.”

It’s tempting to see here the direct predecessor of something like the package of angels and apocalyptic warfare that was taught at Qumran, and which would characterize both Christianity and Islam. That association is suggestive given the coincidence of timing with the era of Persian rule.

Malandra supplies a useful summary:

What emerged during the Achaemenid period was an eclectic Iranian religion, Zoroastrianism, which contained elements of Zarathuštrianism, apocryphal legends of the prophet, a full pantheon of deities that are almost entirely absent from the Gathas, an overriding concern over purity and pollution, the establishment of fire temples, a strong ethical code based on man’s part in the cosmic struggle between the principles of the Truth and the Lie, and an eschatology which saw history as an unfolding struggle between these principles, which would lead to the final Renovation of the Cosmos.

Wisely, Malandra is very cautious about direct Zoroastrian influence on Judaism and Christianity in “ideas such as a trans-historical mašiaḥ [messiah], heaven and hell, and a day of judgement.” This is, he says, “a significant question, for which there are few definitive answers.” The chief lesson is that we should we careful about blithe invocations of “Persian Dualism.”

So what about angels? Let me return to this in my next post.

And to end with a quick note of linguistic déjà vu. The Zoroastrian word for evil, falsehood, the lie, is druj. I grew up in Wales, home of another Indo-European language. In Welsh, the word for bad or wicked is drwg. I feel quite at home.